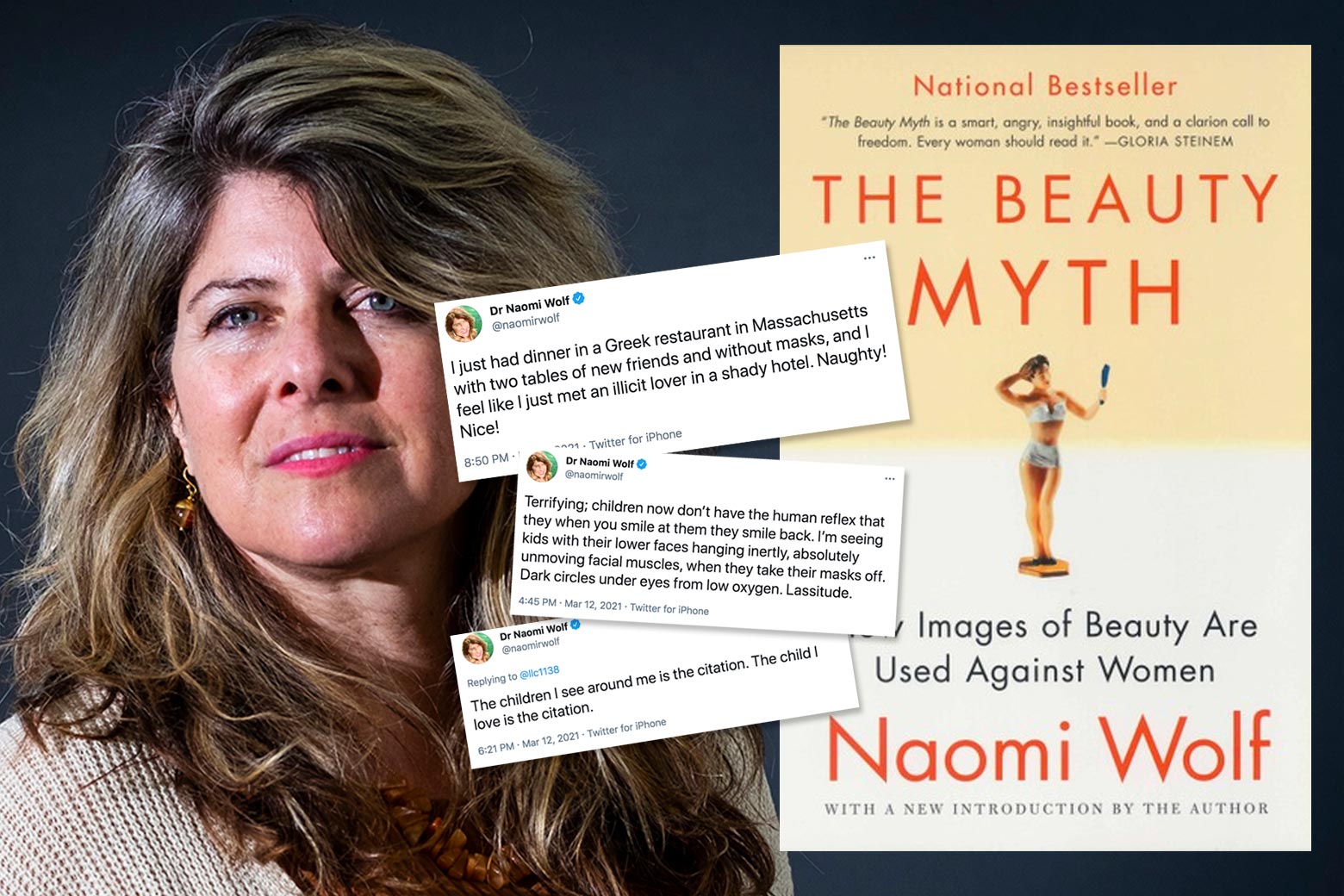

First, it must be said: Naomi Wolf is a COVID truther. The bestselling author spent the pandemic doing things like celebrating indoor restaurant meals and declaring that children are losing the reflex to smile because of masks (when asked for evidence, she stated: “The children I see around me is the citation”). She went on Tucker Carlson in February—not long after an actual coup attempt—to warn that the United States was “moving into a coup situation” because of COVID restrictions. Just this week, she shared a 1944 photo of a Jewish couple in the Budapest ghetto wearing stars on their jackets, with the caption “Biden: ‘Show me your papers.’ ” There were many pre-COVID portents of Wolf’s conspiracy turn: In 2019, she was sharing suspicions that oddly shaped clouds were manufactured, and getting corrected on live radio for disastrously misunderstanding historical documents on which she hung the thesis of an entire book. The first time she went on Alex Jones’ show (but not the last) was in 2008.

This has all been unsettling to watch because Wolf’s work once transformed me. Just over 30 years ago, she published the text that launched her to fame in the first place, The Beauty Myth. The book describes a set of punishing cultural practices that, she explains, had been “designed” to oppress women newly liberated by second-wave feminism. It was a bestseller embraced by big-name feminists. When I was 15, a few years after it was released, the book landed in my hands, probably at one of the Unitarian Universalist youth conferences I attended as a ’90s neo-hippie growing up in New England. It marked my first experience reading something that linked my secret shames and fears to a Big Problem in the Culture. My time as a fan of Sassy magazine, which was constantly critical of mainstream teenage girl culture, primed me for Wolf’s book. But The Beauty Myth had none of the fun and personable “you could make a skirt out of ties!” voice that leavened Sassy’s riot grrrl politics. The Beauty Myth tied the daily problems of teenagers to the larger plight of women, affirming me in my suspicion that my everyday issues were not something I’d grow out of—they were serious.

I was furious at having to be a teenage girl—angry to see girls skipping meals and betraying friends (betraying me) in favor of boys. I was even angrier that I felt like doing all that, too, because nobody wants to be a wallflower. The Beauty Myth gave shape to all that anger. After I read it, I started wearing overalls all the time; I went barefoot whenever I could, and used only body glitter for makeup, because—I’d tell anyone who’d listen—I thought it looked good. I wrote several overwrought term papers about anorexia nervosa, which my professors received with admirable tolerance. The book traveled with me from camp to school to home, sitting on the shelf of every room I inhabited between the ages of 15 and 21, before I replaced it with Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass (a truly Hall of Fame upgrade). Now, watching as Wolf uses her platform to happily elevate every lockdown skeptic and anti-vaxxer with a Substack, I wondered whether this formative text ever had any value at all, or if Wolf had been misguided all along and I was just too young to know it. So I picked up the book again, for the first time in 20 years.

The Beauty Myth is organized into six chapters with what now strike me as grandiose titles: “Work,” “Culture,” “Religion.” In revisiting them, I found flashes of insight about the human condition. Analyzing beauty’s function in fiction, Wolf writes of Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles: “Without her beauty, she’d have been left out of the sweep and horror of large events. A girl learns that stories happen to ‘beautiful’ women, whether they are interesting or not. And, interesting or not, stories do not happen to women who are not ‘beautiful.’ ” That’s something I’m glad to be reminded of, as I consider which stories to read to my own daughter. And as I revisited Wolf’s chapter on diet culture—and how it can rob women of their quality of life—I found myself nodding along. I remember my teenage self finding that chapter to be a huge relief. I now know that fat liberation activists got there way before Wolf, and that’s clearly where she’s getting these ideas, though she was the one who rode them to fame. She does quote the work of Susie Orbach (the psychotherapist who published Fat Is a Feminist Issue in 1978) and others, though I wouldn’t have recognized those touchstones when I first read this in 1995.

I can see now that Wolf excelled at spinning out little fables about the effects of the “beauty myth” on women and men—little tales that weren’t about real people, but still somehow manage to ring true. Sometimes, these effectively help make an abstract concept concrete. There’s a particularly prescient passage about the way female beauty’s use as currency poisons intimate relationships:

What becomes of the man who acquires a beautiful woman, with her “beauty” his sole target? He sabotages himself. He has gained no friend, no ally, no mutual trust: She knows quite well why she has been chosen. He has succeeded in buying a mutually suspicious set of insecurities. He does gain something: the esteem of other men who find such an acquisition impressive.

This unhappy couple lives only in Wolf’s mind. As a teen, the story mostly seemed theoretical to me—but reading it now with the benefit of age, and after having witnessed the Trump presidency, it rings intensely familiar.

But for each of the little pieces that were useful, or at least reinforcing to my 2021 self, there were many more that were utterly cringeworthy—thought experiments gone wrong. Throughout the book, Wolf compares women’s oppression to that suffered by various other groups, with the express purpose of highlighting just how bad modern women have it. At the time, critics objected to the comparison between anorexics and concentration camp survivors (a nice bit of foreshadowing of 2021 Wolf’s Twitter habits), but what jumped out at me the most on my reread were the clunky bits of analysis using race. If women feel they need cosmetic surgery to keep a job, Wolf suggests, that’s comparable to what might happen to an enslaved person whose owner might legally cut off a foot to exercise control. Just as a Black employee can argue that he “should not have to look more white in order to keep his job,” Wolf writes, a female employee should have a parallel right to be loyal to her “female identity” by resisting surgery and dieting as she ages (Black women, who might be experiencing both forces, do not seem to factor in here). And “airbrushing age off women’s faces has the same political echo that would resound if all positive images of blacks were routinely lightened.” Reading that thought, 2021 me breathed a deeply felt Yikes!

Sometimes, the book’s leaps of logic are simply comical. Wolf notes that the beauty industry loves to talk about the perils of “photoaging,” which is perhaps true and even a little annoying (let us have sunspots in peace). But she goes on to say that were it not for this emphasis, women would be outside “on the environmental barricades” defending the ozone layer. “This sun-phobia mentality is severing the bond between women and the natural world,” she writes. This is a strange assertion on a number of levels—the beauty industry also loves to sell sunscreen; there are such things as hats; and if all else fails, you could just sit in the shade and still be outside, bonding with a swath of the natural world that happens to be next to a tree. Her worry about our supposedly incredibly fragile connection to the outdoors seemed, to me, to be a harbinger of the rhetoric Wolf now uses against face masks. She’s interested in defending whatever she sees as essentially “human” (sun on skin, visible smiles). Less often does she question why, in a world where we are basically animals who wear clothes, it’s a particular point of intervention in the “natural order” that bothers her.

The main problem, though, lies in the book’s vision of power. The writer is convinced that some superstructure, somewhere, is consciously manipulating culture to oppress women. The “beauty myth,” in her construction, isn’t a trend or a paradigm or a zeitgeist; it’s something more literal. The idea that there’s a standard of beauty that women suffer from attempting to adhere to is “not a conspiracy theory; it doesn’t have to be,” Wolf writes. “Societies tell themselves necessary fictions in the same way that individuals and families do.” That’s true! And well put. But then she returns over and over again to, well, the idea that there really is a conspiracy theory at play here. “Somehow, somewhere, someone must have figured out that women will buy more things if they are kept in the self-hating, ever-failing, hungry, and sexually insecure state of being aspiring ‘beauties,’ ” she muses. Sometimes it’s employers; sometimes it’s “the power structure”; sometimes it’s a shadowy force, obscured with the passive voice. Fashion models are “an elite corps deployed in a way that keeps 150 million American women in line,” Wolf writes. In my pre–Beauty Myth days, I thought if I just dieted a bit I could maybe go to one of those Barbizon modeling courses advertised in the back of teen mags, so I know what Wolf means by “in line.” As an adult, I’m just not sure who’s in charge of this “corps” and doing all the “deploying.”

Wolf the star feminist and Wolf the science denouncer share an animating principle: the tendency to feel strongly about something, then decide that the intensity of those feelings means that there must be somebody responsible. It’s this intensity, linked to a clear cause, that connected so well with me as a teenager. After I put down The Beauty Myth, I worked at a teen magazine and saw up close how the economy of beauty worked. I went to grad school, read a lot more cultural history, and realized that the more airtight a scholar believes their explanation for cultural change to be, the less they should probably be trusted (not that it takes a Ph.D. to recognize Wolf’s flaws). I can see this progression of Wolf’s thinking in every Trump- and COVID-era conspiracy theorist, from Stop the Steal to QAnon, who, like Wolf, seems to favor a “natural order” where their particular problems rank first. It goes from “this sucks so much” to “someone is surely pulling these strings” to “guys—I found the someone!”

It’s an effective tool for storytelling. Wolf’s conviction animates the book’s long and ungainly paragraphs, dictating its inclusion of anecdote and gory detail and so, so many statistics. (One of them, on the number of women who die from anorexia, was criticized at the time for being grossly inflated, though Wolf corrected the error.) Caryn James wrote in the New York Times, in a mostly negative review of the book when it came out: “The Beauty Myth is a mess, but that doesn’t mean it’s wrong.” But looking back at the book, on its 30th anniversary, with its author lost to the world of conspiracies, I’m not so sure. The book freed me from a lot of young adult fretting, and I know it did the same for others. But I don’t think that the ends justify the means—especially now that we see just how destructive Wolf’s ends can be. By some historical accident, I’ll always owe The Beauty Myth a large part of my own feminist identity. But it’s not a fairy tale I’ll be handing to my own daughter.