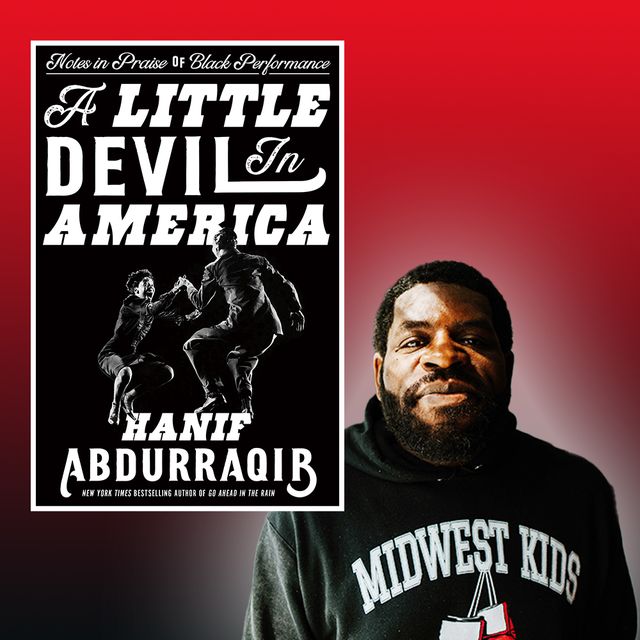

Just like so many other people across the world, poet Hanif Abdurraqib has had a rough year. He’s well known for his ability to enrapture a crowd with his live readings and storytelling (as well as his infamous book-signing lines that stretch for hours), but a global pandemic has put the brakes on one of the poet, essayist, and cultural critic’s most beloved forms of connection with readers.

“I struggle a bit with Zoom,” he tells me when we speak (via Zoom, of course) to discuss his new book, A Little Devil in America, “because I love being in a space. I love hearing the machinery of a place, the movement, the breathing of people during silences, or the laughter of people, the air-conditioning machines, bringing to life these kinds of things. If you’re going to a bookstore, the kind of rattling of the shelves as someone moves along.”

The best-selling author — who rose to national acclaim when his essay collection They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us was named a book of the year by NPR, Esquire, BuzzFeed, O: The Oprah Magazine, Pitchfork, and the Chicago Tribune, to name just a few publications — has instead spent the past year pushing his writing to new heights and just simply “doing his best.”

“I’m someone who organizes well here in Columbus,” Abdurraqib says, “and so I think retreating into what I always do, which is trying to find out what the needs of the community I’m in directly are and to see how I can serve those needs as best as possible. Because I do believe that, for me, community solidarity is the only way forward. I think that my exhaustion is largely secondary to the needs of the community, and, when I come together with people in a way that feels uplifting or like it is moving a needle in some direction, I think my exhaustion washes away a bit. But, yeah, I mean, it has been a frustrating year and a frustrating era of living. That frustration probably is on a sliding scale, depending on who you are, where you are, how you identify, these types of things. But building up solidarity in the community I live in is a really important thing for me.”

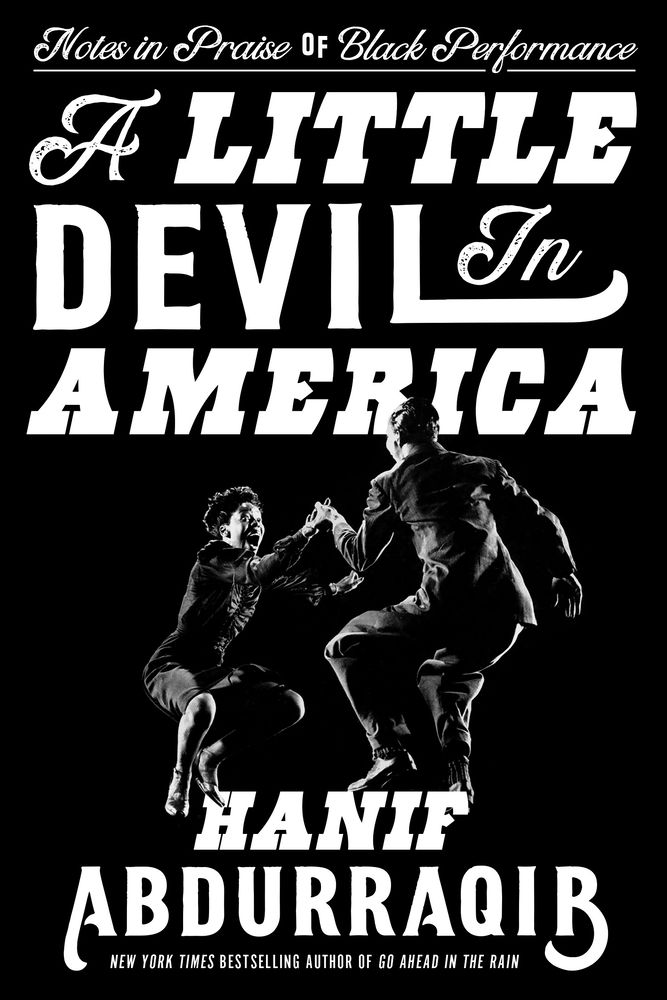

Taking that sentiment in mind when thinking about the author’s new book, A Little Devil in America: Notes in Praise of Black Performance, makes a lot of sense, as some of the work’s most poignant and engaging moments come around the concept of community in some way, whether that be in a Soul Train dance line, movement, and dance itself, or even the horrific history of dance marathons and endurance contests.

Employing his signature style of skillfully weaving personal essay, lyrical prose, poetry, and cultural criticism, Abdurraqib produces the best, most polished, most accomplished, and perhaps most personal book of his illustrious career. One of the very best books of recent years, A Little Devil in America builds on the foundation of the author’s previous works and explodes expectations into a personal history through lived experience and lifetime joys. It is a book that brims with wonder and introspection while also honoring the significance and contributions of so many of the lives within it. Abdurraqib’s passions are fully on display, and his widespread love is infectious in the best way possible, resulting in a masterwork that will not only move readers but will also send them off into their own personal rabbit holes of joy and wonder. This is, perhaps, the greatest gift a writer can give to his readers, and A Little Devil in America delivers it in spades.

SCOTT NEUMYER: I want to say that I unabashedly love this book. It’s easily one of my favorite books of the year. Can you tell me a little bit about how it came about? It really does feel like a logical progression of your previous work, culminating in something incredible at just the right time.

HANIF ABDURRAQIB: I was trying to think about a book that felt to me just ritually historical but also celebratory and not kind of scratching away at trying to find a conclusion for anything. But mostly approaching ideas, having a sense of wonder, and asking people if they would be perhaps willing to join me in approaching these ideas with a sense of wonder. For me, the book was such a visual experience where I spend so much time looking at photos or watching archival footage, or reading old interviews, and trying to enliven those experiences on the page and trying to make people eager to go seek, on their own, the things that made me excited. And so, a big part of the process of this book was sharing my excitement and hopes that it can kind of braid together and connect other people to my excitements and extend them beyond myself.

SN: Your passion for what you love is infectious, and I think that really comes across in this book. One of the things that I really love about it is the beautiful way that you weave personal essay and lyrical prose and poetry and cultural criticism into something that just works. How difficult is it for you to find the right balance of each?

HA: It doesn’t feel difficult in the moment. I spent a lot of time kind of orbiting my obsessions. I think, because I spend a lot of time marinating in them and sinking into them, they become personal. Whether or not I wanted to, I began to see myself in my history, through the lens of my obsessions. So it was easy for me, after watching hours and hours and hours and hundreds of hours of Soul Train, to begin to kind of spiral into a fantasy world where there’s some ancestral connection between how I ended up here and perhaps to people who danced along a Soul Train line once. I think to sink into my obsessions with a real generosity is to allow myself the fantasy of a deeper personal connection than might otherwise exist. And so, in doing that in my writing, I feel like I have to validate that. I have to make that make sense in my head. I have to parse that out. And so, naturally, I think these personal connections come easy. Or at least they come easy to me, and they don’t feel overwhelmingly difficult.

SN: Do you ever feel the urge to let one form take over in a book like this?

HA: No, mostly because I let the language and the work and the narrative tell me what it wants. I perhaps don’t have a big enough ego as a writer. And this isn’t saying other writers have large egos, but I think that I am very uncertain as a writer. I don’t feel enough certainty as a writer to assume that I have full control over an idea and how it appears. I have some control, of course, but through the course of writing I think the narrative and the choice of language and all these things as they appear on the page shift and demand things out of me in real time. And so I have to respond to that. And I have to honor that and try to wrestle control back for whatever flimsy ideas I might have on my own. I think it’s a type of humility or like I’m giving myself up to the work in knowing that my impulses are at their best when they follow the trajectory that the work is taking me on, and not when I’m trying to drag the work back to a place that I am more comfortable.

SN: Do you consider it almost like a bit of impostor syndrome?

HA: I don’t even know if it’s impostor syndrome with me. I don’t think I feel impostor syndrome in any way. But I do think that there’s a type of anxiety that haunts my life and therefore my thoughts, my processes, and my writing. And instead of letting that haunt me in a way that doesn’t feel useful, I think that I’ve opted to kind of wield it in a way that allows me to respond and be malleable to a writing process and not find myself beholden to my ideas. I think ideas are required to have fluidity because, you know, to live life as a person who’s as anxious as I am really requires a type of fluidity and ability to adjust, emotionally and structurally. I don’t know if it’s impostor syndrome as much as it is kind of just being haunted by the noise of my own brain and choosing to lean into that a bit.

SN: I feel like part of that, though, is what makes your work so good. There’s a vulnerability there that I think reaches people. Would you agree with that?

HA: Yeah, I think so. My hope is that I’m never someone who comes across as though I’m trying to present myself as an expert. I hope that I come across as someone who is unafraid to be wrong, and to kind of revel in my ability to be incorrect as a tool of celebrating new information and celebrating the coming to new information with a lot of excitement, in pleasure for where that can take me in my thinking. And I think that perhaps is a type of vulnerability. I think I’m more eager to cash in on the vulnerability that I can achieve through a comfort with wrongness. In not seeing wrongness as an indictment of my full self, but instead as a real opportunity to build something newer and better out of my thinking that serves me individually, of course, but also serves the fluid and ever-changing communities I’m a part of.

SN: And it feels like an opportunity to learn and grow as well.

HA: Oh, yeah. I’m always up for that.

SN: Recently on your Instagram, you talked about how much of this book means to you, and in particular how much some of your previous books took out of you. Do you think vulnerability feeds into the way that your work can be so physically exhausting, visceral, and even scary for you at times?

HA: At times, yeah. I hope this book is a gateway out of that, though. I hope this book is a gateway to me learning how to not be put through the emotional or physical or mental wringer due to the process of creating something. What’s great, or what feels good to me about this book, is that I am not trying to push it away from me as soon as I can. And so, you know, we’re not done with each other in a way, in getting past the idea of when I finished the product, I’m done with the project. I’d like to move past that idea, and I think with this book I have. And I think that because there are so many things, so many different ways I think about performance and Blackness that I have leapt to the forefront of my mind when I consume pop culture now, if I’m not like, “Oh, dang, I wish I could have put that in this book. I wish I could write about this for people to see it.” Sometimes I just like the excitement of sinking into that without sharing it with the entire world. And I think that’s how I know I perhaps evolved a little bit beyond this idea of every excitement has to be a project that everyone can see. You know, I think this book allowed me to say some things I’m excited about, but I want to keep just for me.

SN: You have these fascinating, eclectic interests — pop-punk and emo, hip-hop music, sneakers, fashion — all these things, but does it feel like you need to keep some of that stuff for yourself? There’s that feeling of when you get the job that you’ve always wanted, it becomes less fun and more of a job, right?

HA: Yeah, but I think this is a privilege. If I’m writing about where I’m at now, you know, it hasn’t always been like this. If I’m writing about something now, it’s because I want to write about it, and I want to share my excitement about it. And, you know, that’s kind of just where I’m at. And for me that makes it a lot easier to engage with the work in the world. And it makes it a lot easier for me to delineate the things that I believe are just mine or that I want to be just mine, or that I keep in a small circle of folks. Then I’m also someone who’s excited about having broader conversations with the public about it rather than just writing a thing and saying, “Well, you have that now, and you can respond to it.” I like asking people what they think about things or asking people to tell me what they’re interested in. I just dislike hierarchies and want to dislodge myself from the hierarchy that kind of gets created of this writer who is an expert on a thing, dictating something to the public. I’d rather just ... I love talking to folks about sports or about what they’re listening to or whatever. And I would rather do that than anything.

SN: It’s more about the conversation.

HA: Yeah, I think with social media and so many platforms that exist now, we do miss things that we don’t in person. I think people who have been to my Q&As or my readings know that I really cherish those. Because it’s a good opportunity to kind of just talk about stuff, I always tell people to just tell me about what they’re into, or what I need to experience differently than I’m experiencing it. That’s important to me.

SN: You can see that in your social media too. It’s so interactive, and it always feels like you’re opening up to more of a larger conversation. And I appreciate that, especially when not as many people are doing that.

HA: Yeah, I mean, it’s fun for me too. I think I was doing this a lot before the pandemic anyway, but I think in the throes of the pandemic — I live alone with my dog — and so I am trying to populate my living with not just the excitement that I feel but understanding what other people are excited about as well.

SN: In one of the very first essays in the book, about dance marathons, Don Cornelius, and Soul Train, it feels like you were setting the stage for what’s to come throughout the rest of the book. Is that the reason you decided to lead with that essay because it encapsulated so much about what the book was ultimately about?

HA: Yeah, I mean, that piece feels like a thesis statement for the project of the book as I saw it. And also, you know, that that piece is really, especially about movement in dance and the connectivity of bodies moving together, or movement as survival, even. And that, to me, felt like a thesis statement for what the book was attempting and where the book was trying to go. And the Soul Train stuff was at the top of my top of my head because I was spending so much time watching Soul Train. And so to honor all of those things at once, I wanted to open the book with something that I was excited about, something that got me going immediately and instantly, and that was where I landed.

SN: One of the things in that essay that stands out to me is surrounding the Soul Train line. You say, “The line was an instant hit because it afforded each person their own time to shine.” And then, “The Soul Train line became an essential part of the Soul Train viewing experience. Black people pushing other Black people forward to some boundless and joyful exit.” Is there anything that you can think of now in popular culture that does the same thing for Black people? Is there anything that’s taken Soul Train’s place?

HA: Well, I don’t know if anything could take Soul Train’s place, but, of course, Black people that I know, at least, are — I think because of the advent of social media and all this — find our excitements in many things. The shared watching of certain TV shows. One thing about Black folks that I love is that there’s so much innovation around the shared consumption of popular culture that it is sometimes enriched by our regional differences. There are many modes of Blackness depending on where we’re from, where we came up, where we migrate to, all of these things. And Soul Train embodies that to some degree, of course. But what I love now is that I can connect with Black folks watching the same thing, in some cases across the globe, and share these joyful reactions.

SN: The section in that essay on dance marathons destroyed me. Do you think that dance marathons and other endurance contests like the old “hands on a hard body” contest are exploitive, especially of marginalized groups of people in ways that it’s just difficult for those empowered to understand? It almost seems like simply trying to vote has become this new form of the dance marathon or the endurance contest for many people, unfortunately.

HA: Those Depression-era dance marathons are horrifying. I think the fact that there were spectators is maybe the most horrifying thing for me. If you read about it, some of the spectators were not that far off in terms of class. There wasn’t a massive class divide always between the spectators and the dancers. But those who are maybe just a little bit better off — watching those dancers allowed them to kind of have power. Being able to comfortably watch allowed them to have power. Some of this too is the question of what an endurance test looks like in America. Sometimes, you know, depending on the identity of those engaging in the endurance test, it is not as physical as a marathon. But there’s something embedded into the living experience that cannot be shaken free from, and so it becomes almost the ever-present background noise. It does not blend in. You’re always aware of it. But you’re also aware that it’s a little bit harder to break free.

SN: I feel like books like this, in a way, help though, right?

HA: For me personally, I don’t think the writing of a book gets anyone free. And I don’t think my writing of a book gets anyone free. I mean, there’s a way that this book can adjust some thinking around the full humanity of performers and performance. That’s great. But I think political education and community solidarity and revolutionary upheavals of oppressive state apparatuses — that actually gets people free. That doesn’t mean that I’m ashamed I wrote a book. I’m just not overselling the potential. ... There have been countless books that have been read that I’ve loved, maybe people have loved, and that has yet to shift the cultural consciousness of America on the whole. Perhaps this is a cynical outlook, but I just don’t think that my writing of a book is going to get anyone free. Which doesn’t mean ... Again, I am proud of this book. I’m proud of the work in it. I definitely did my best with the tools I had. And I’m thrilled about that. But I don’t want to oversell the potential for what it can do in the world. My hope is that it is pleasurable to read, and it sends people down some joyful rabbit holes.

SN: You’re described as a poet and essayist, a cultural critic, and your work has touched on all of those elements. Do you ever get the urge to write fiction or a novel?

HA: No, no. I mean, I think I’m someone who, if there is one strength that I think I have, it’s that I know my limits. And, you know, I have a pretty poor fiction-reading practice that I’m working on. You know, it’s funny, because I grew up reading primarily fiction. And I love fiction. It’s not like I’m averse to fiction. I just kind of feel like I require a level of focus getting into fiction that I haven’t been able to tap into for the past year or so. But a goal of mine this year is to kind of reform and rejuvenate my fiction-reading practice. And when I read good fiction, when I’m present with fiction, it seems like a real impossible task for me to write, you know, where I’m just so in awe of the work. I’m often in awe of poets and nonfiction writers, but I think what I am in awe of those folks — it’s very, like, I find myself asking, “Well, how did this happen?” or “How did this get made?” But I think there’s a part of my brain that can, if not make a path to do that, can make a path to understanding that. But fiction, I’m always kind of like, “I don’t know if there’s any way that I can wrap my head around the crafting of this, or how this was crafted.”

SN: One of the things that you’re well known for is your ability to perform your work in public onstage and really move people. How difficult has it been for you over the past year to not have that outlet?

HA: What I really miss is the post-reading moment, the Q&A and the book signing where you can talk to people. I get engaged with people who come out. That, to me, is the most exciting thing, and you have so much gratitude for booksellers and event runners and people who stay while the book event happens because I know my book-signing lines are kind of notoriously hours-long at this point, but it’s in part because I just love getting to talk to people. I miss the post-reading wind-down interaction with folks. Signing a book is a cool thing. I don’t want to make it seem like it’s trivial. But for me it’s like someone coming up and is, like, not just handing you a book but telling you a story. Because I’m hyped on that.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Scott Neumyer is a writer from Central New Jersey whose work has been published by The New York Times, The Washington Post, Rolling Stone, The Wall Street Journal, ESPN, GQ, Esquire, Parade Magazine, and many more publications. You can follow him on Twitter @scottneumyer.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY