The world in which Lauren Groff’s Fates and Furies became a national phenomenon was decidedly different from 2021, at least on a surface level: The Atlantic declared 2015 “the best year in history for the average human being,” a laughable departure from our recent state of political and pandemic-born tohubohu. Yet the parallels to our current landscape were everywhere: the police killings of Walter Scott and Freddie Gray; the mass shooting at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston; the steady, creeping rot of racism, oppression, and misogyny permeating the fabric of our communities. Groff, the National Book Award-nominated mastermind who also imagined the worlds of Arcadia, Florida, and The Monsters of Templeton, is finally releasing her next novel, Matrix, this year, in a world she’d argue has not shifted as much—not in six years, not in hundreds—as we might think.

Matrix is set in the 12th century and follows real-life poet Marie de France, a 17-year-old cast out of the French royal court and sent to England to be the new prioress of an ailing abbey filled with sick and starving nuns. At first shocked by her new life but soon humbled by it, Marie finds purpose and spiritual fervor in this all-female enclave and commits herself to blazing a new trail for her devoted sisters. But her nation and era cannot make sense of a woman like her, and that shortness of vision could eclipse her dreams before she has the chance to nurture them.

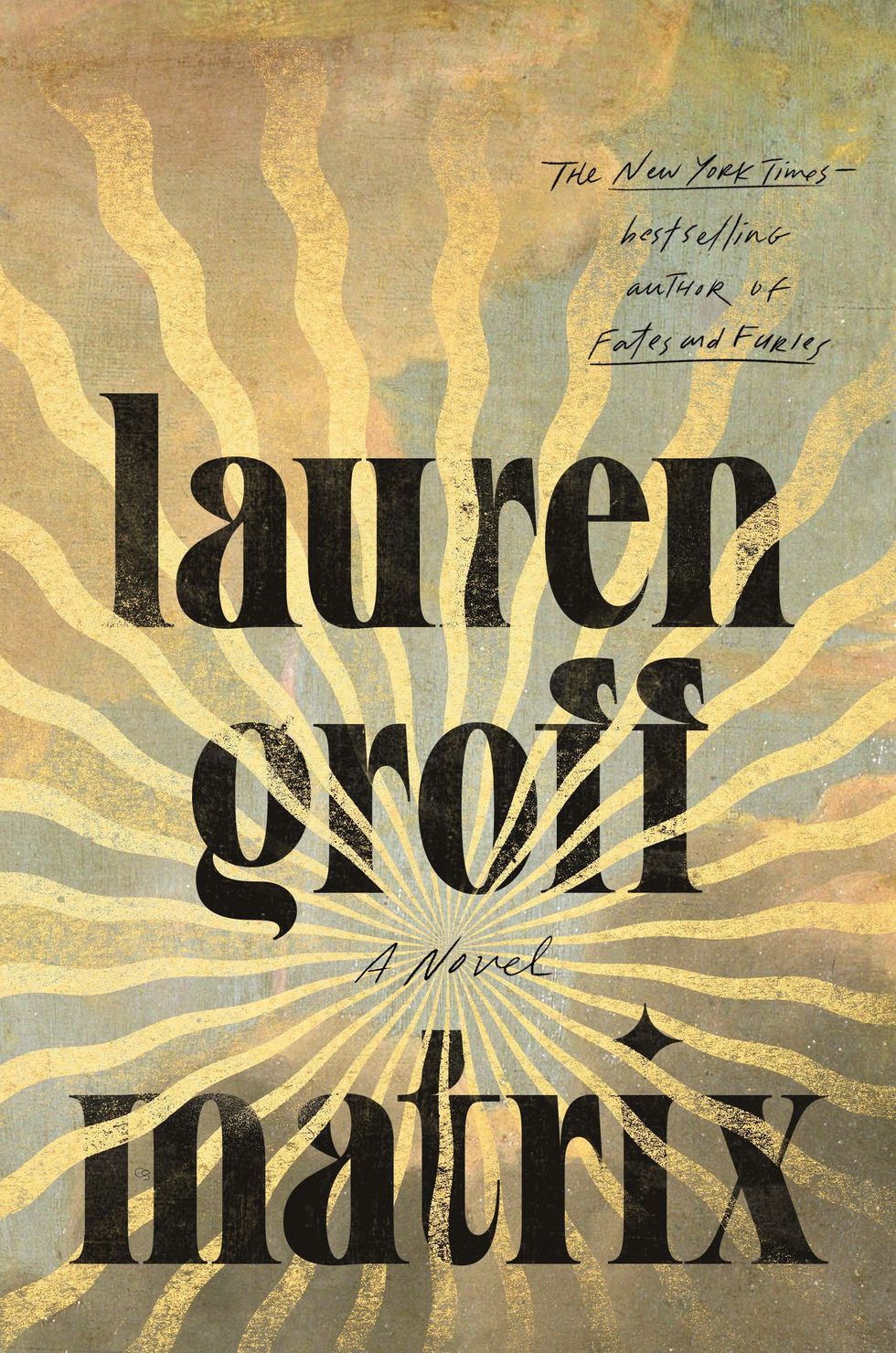

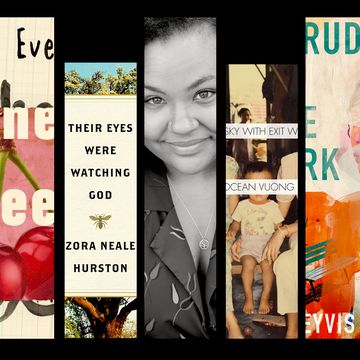

In an ELLE.com exclusive, Groff reveals the cover for her new novel and dissects how writing about the past always reveals something about the present, too.

Your first novel since Fates and Furies takes a dramatic shift from your usual contemporary settings. How did you land on this particular setting and where did the idea first come to you?

I was actually working on a different novel, which is also historical in nature, about 1609 in the Americas. I was at a fellowship when I heard this incredible friend of mine, Dr. Katie Bugyis, give a speech on medieval nuns’ liturgical notes. I thought going in that it wasn’t something I would be interested in, and it just sort of exploded my brain. I had learned to read the romances of the 12th and 13th centuries in college, and it all came back to me. Matrix came out of Katie’s talk. This was also in the middle of the Trump presidency, and I was exhausted. I just wanted to live in a female utopia, not worrying about men at all. And how else could you do that but go back to a nunnery, back in the days of Benedictine enclosures, where you’re just surrounded by women? It was the right lecture at the right time, which just lit the wick.

Your main character was a real person, Marie de France. When you were conceptualizing Marie, how much came from historical text, and how much was your own creation?

Luckily nobody knows all that much about Marie de France. She’s a person that’s sort of shadowy. There are suppositions about her being an abbess, the illegitimate sister of the king, but again, that’s kind of a beautiful place to go, back into history, to find clues from her own records. And those scholars who’ve read Marie de France will be overjoyed to find a lot of Easter eggs throughout the book, joyous little moments that actually show up in her poems, showing up in the life of my character.

I leaned a lot on very serious literary books of historical fiction—like Penelope Fitzgerald's The Blue Flower, which gave the outlines of what is known—but in a light way, so that one could get into the sort of interpersonal issues of the characters, these invented characters, which I found really exciting and fun and fascinating. And the thing about historical fiction, too, is you cannot not talk about the contemporary world, because we are creatures of our moment. And so while Matrix is about the 12th and 13th centuries, it’s still also about the 21st century.

Where did the title come from?

First of all, “matrix” comes out of the Latin for “mother.” And the abbess is obviously the mother of a community. Even if she doesn’t give birth out of her own body, she’s still the interlocutor between her nuns and God. But also, matrix, it’s just such a fascinating word! I went down eight different rabbit holes: It applies to mathematics as sort of a gridwork in which you see things. It applies to sculpture as the foundational mold out of which you create plaster casts or records or things like that. In geology, it’s the bedrock in which you find gems. It’s the pattern, the original pattern. It was such a beautifully expressive word to talk about the potential model that might’ve been lost or that was lost through time, as a lot of voices of very powerful women have been lost through time.

You’ve described your own religious upbringing as this sort of paternalistic, harsh Christianity. But it left its mark on you in profound ways, and many readers will see the Biblical influence in your work. I’m curious how that background impacted the way you thought about this novel, especially given its religious setting.

I’m so ambivalent about my preliminary religious training. Part of it is profoundly hierarchical, profoundly patriarchal. And I resist that in every fiber of my being. But at the same time, when you are versed in Biblical narratives, you’re versed in the most rich and gorgeous stories. It’s the best training for storytelling, I think, in some ways.

I’m raising my children secularly and I feel very bad about it, because they’re not getting this underpinning of knowledge. They can’t read Paradise Lost and understand what is meant by all these little asides that are happening. And they could learn that in the future—that’s part of a classical liberal arts education—but when one is given religion, one is given the stories of the religion, and that’s just profoundly…it’s the deep tissue of my storytelling and it has been throughout all of my work.

And it’s something against which I can write, too. Often, when you’re writing novels, you’re not only writing toward things. You’re also pushing against them as you’re working. It’s an oppositional art, and it’s really beautiful to have these deep, deep narratives to write against.

In your work, you seem drawn to insulated communities. You have the small town in Monsters of Templeton and a cult in Arcadia, and of course, the abbey in this book. What fascinates you about these small groups?

I don’t really see the world in bifurcated ways, but I do feel as though a lot of the tensions that are happening to us right now are tensions that arise out of an imbalance in the impulses toward individualism and impulses toward communal living. I know that’s really reductive, and I don’t mean to be reductive at all, but I do think the political struggles we are undergoing now are informed by this unsettled push and pull. While novel-writing feels intensely individualistic, it’s also never individualistic. It’s always communal, because a novel just exists until there’s another person to read it. It’s sort of a floating bunch of words on dead trees, and it’s the reader that actually creates the novel themselves. And when you write a novel, you’re not just writing for yourself; you’re sort of joining into the larger cultural, artistic river that all humans have collectively created.

I’m trying to understand the difficult balance between individualism, particularly American individualism, because a lot of our political struggles are based on this very intense matter that we’re having such a hard time even articulating—the way we are beholden to each other; the way that, in our society, we need to actually look out for each other. Art is the field in which one can explore these issues without devolving into binaries or dissolving into tightly knitted explanations.

You’ve said that, even now, you never really feel like you know what you’re doing. Was that still the case when you were writing Matrix?

Oh, yeah. That’s the joy and the glory of sitting down every day. Sometimes I will write a novel between other novels that feels easy and I won’t publish it, because if it’s not challenging for the writer, the likelihood of it being challenging to the reader is very, very low. So even though I have no control of the way that any of my books are going to be received, if anyone’s going to like them, I do have control over how engaged they make me feel toward the world and toward other people. That’s what you’re seeking when you sit down.

You’ve said that you never want to write the same thing twice, but did you find similar patterns as you wrote Matrix that you’d also discovered in Fates and Furies or Arcadia and the like?

A lot of times I don't see [themes] until after the fact. Someone will say something to you and you’re like, “Oh my God, I wrote another community novel. You’re right, I only talk about community, I guess.” I think that we are inadvertently always telling on ourselves in some ways. I’m certainly probably a community writer, a writer about God. Most of my books have something about God. I’m a writer about women and longing, but to be honest, it’s so hard when your face is pressed to the rug to see the pattern.

How has the pandemic impacted the way Matrix will be delivered into the world? How has it impacted the way you think about the book itself?

I was finished with it before lockdown happened last year, and I spent a lot of the last year refining and editing and trying to make it better. But the truth is I don’t have any idea. It has been a very challenging time. I think there are a lot of people struggling right now, a lot of artists in particular struggling just to find the space and the time. I think giving ourselves the grace to be fallow is always a challenge, but it’s always something that we need to seek for ourselves. That has been something I’ve been struggling with a lot, just the feeling of not being productive, but also thinking about why we need to be productive. Do we really need to be capitalists in terms of art? Is that really something that we want art to even be subject to?

I think we’re going to have a lot of brilliant work come out of this time. It may take a while and it may not be directly about the pandemic, but it’s going to change the course of literature, and I have great optimism about it.