The albatross filled with plastic suffered. Susan Middleton wanted to make sure I understood this.

Jen and I flew to San Francisco, which put about 900 pounds of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Susan invited us on a bright spring day into her office in the basement of the California Academy of Sciences, below the ground of Golden Gate Park. The basement serves as resting place for twenty-six million plant and animal specimens. The word comes from the Latin specere, to look at. This basement also houses artifacts (which are things made by people) and scientists carrying out the academy’s mission: to explore, explain, and protect the natural world.

Explore, explain, protect. To boldly go. But Susan Middleton is not a scientist. She’s a photographer. She had recently photographed the Academy’s collection of specimens for a book called Evidence of Evolution. Mostly, though, she takes portraits of living plants and animals. In 2003, she and her colleague David Liittschwager traveled to Kure Atoll in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands to document the birds and plants and sea creatures there.

Hawaiians call Kure “the elder,” said Susan. It is the oldest of the Hawaiian Islands, moving like all the others slowly northwest on the Pacific plate, eventually to disappear beneath the water.

In fact, Kure the island is already gone. The atoll represents the submerged mountain’s coral remainder, the skeletal base of countless translucent creatures eroded over time to fine sand.

The photographers almost didn’t get there. At fourteen hundred miles northwest of Honolulu, Kure is, from the human point of view, the most remote atoll in the planet’s most remote island chain.

The albatross filled with plastic suffered. Susan wanted to make sure I understood this.For the albatross, Kure is one of the few places on Earth it comes to rest. The bird spends its life in flight, ranging over thousands of miles of water, sleeping and feeding in motion, landing only to breed on specks of ground surrounded by a liquid horizon.

In-spire. The albatross is filled with air: Tiny sacs pack the vault of its ribs, curving around its organs and extending through the narrow bones of its wings that span six feet, eight feet, eleven, the longest of any creature.

Flight. That’s not the right word. The albatross glides, its shoulder and elbow joints locked into place. It avoids the muscle power of flapping; instead it snaps open its wings and dips into global wind flows to cross miles of liquid earth, sniffing out squid, crustaceans, and flying-fish eggs.

No one knew until recently where albatross really traveled. Now people tape transmitters inside the bird’s upper back feathers, so that an antenna sticks out. It sends radio signals to orbiting satellites that use Doppler shifts to calculate the bird’s position: jagged, erratic tracks following food across thousands of miles of open water. Eventually the transmitter battery dies, and the albatross path disappears from human sight.

*

No people live on Kure. It appears in historical records mostly as a site where ships ran aground on the shallow reefs. The State of Hawaiʻi, which manages the atoll as a wildlife refuge, allows no visitors, except scientists and researchers. Susan and David got special permission to go. They caught a ride on a research boat searching out old shipwrecks. They intended to stay on the island three days. They stayed three weeks.

They arrived just before breeding season for the Laysan albatross, a goose-sized bird with a white body and a dark cape. It has a hooked orange beak it uses to spear prey, and pinkish feet. Dark feathers surround its eyes and shade onto its cheeks, making it look dramatic, serious. Hundreds of thousands descend on the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands in winter to mate and lay eggs.

They form a carpet so dense they look like a living snow.

Anyway, that’s how a biologist described the breeding birds. Like Coleridge, I have never seen an albatross. Since it’s an animal synonymous with motion, it doesn’t keep well in captivity.

*

Matter is pitiful; form is terrible.

–Lisa Robertson

The albatross hardly appears in the poem by Coleridge. He names the bird seven times in six hundred lines: when it first becomes visible, flying through fog, the only living thing the sailors see in the land of ice; when it follows the ship for nine days eating human scraps; and when the mariner shoots it with his cross-bow.

At no time does Coleridge describe the bird or give any sense of its physical presence—not even in its fourth mention when the others hang the albatross around the sailor’s neck. The dead bird, lying against his heart, must have been an awkward weight; it must have stunk as it decayed, but Coleridge remains silent on these points.

The albatross is filled with air: Tiny sacs pack the vault of its ribs, curving around its organs and extending through the narrow bones of its wings that span six feet, eight feet, eleven, the longest of any creature.It is the sea serpents that burst to life inside the poem. The mariner recoiled from them at first, monstrous, slimy things. After he is the only living being left on the boat, he looks closely:

Beyond the shadow of the ship, I

watched the water snakes:

They moved in tracks of shining white,

And when they reared, the elfish light Fell

off in hoary flakes.

Within the shadow of the ship I

watched their rich attire:

Blue, glossy green, and velvet black, They

coiled and swam; and every track Was a

flash of golden fire.

There follows a gush: a copious or sudden emission of fluid; a rush (of water, blood, tears).

It is not the poem’s first. The first gush aborts. It dries up. The sailor is surrounded by bodies on a rotting ship on a rotting sea:

I looked to heaven, and tried to pray;

But or ever a prayer had gusht,

A wicked whisper came, and made

My heart as dry as dust.

*

Heidegger also has a gush. In his meditation on the clay jug, he writes that its character consists in holding in and pouring out. The pouring is a giving, he says, sometimes for people and sometimes in honor of a god:

“Gush”… is the Greek cheein, the Indoeuropean ghu. It means to offer in sacrifice. To pour a gush, when it is achieved in its essence, thought through with sufficient generosity, and genuinely uttered, is to donate, to offer in sacrifice, and hence to give.

Heidegger uses the German word giessen, to pour, which his translator renders “gush.” The English word “gush” has a murkier origin. It appears in Middle English with no clear antecedent in Old English or any other Germanic language. The Oxford English Dictionary presumes it is onomatopoetic and cites as its earliest source the poem Morte Arthure, written by an unknown author around 1400. The reference is a violent one, from Arthur’s fight with the giant:

Bothe þe guttez and the gorre guschez owte at ones.

Other sources say the word appeared earlier. According to vocabulary.com: “Gush comes from the 12th-century English word gosshien, originally ‘make noises in the stomach,’ and later ‘pour out.’”

*

Albatross chicks have to grow very fast. They need to mature enough in just a few months to fledge and spend several years in flight without touching land, hunting their own food. The digestive coil inside torments them without ceasing. The parents hear it also, this gush; it pushes them out thousands of miles across the ocean and reels them back. The adults take turns feeding, making constant calculations about how long to leave the nest, how far to fly and in what direction to find enough food to fill the ravenous hole.

*

As I read about the albatross, I also was reading The Odyssey, in its new translation by Emily Wilson, the first woman to publish a major translation of the ancient poem in English. I am struck by the fact that hunger also haunts Odysseus throughout his journey. It brings death to his men who, starving after being marooned for a month, kill and eat the forbidden cattle of the sun god. The flayed hides begin to crawl, and the meat moos on its skewers. Still the men eat, feasting for six days. Once they are back at sea, Zeus hurls a thunderbolt and kills them all for their transgression.

Like Coleridge, I have never seen an albatross. Since it’s an animal synonymous with motion, it doesn’t keep well in captivity.Hunger propels Odysseus to humble himself and beg; its animal need makes him both dangerous and vulnerable. When he washes up on the island of the Phaeacians, he approaches the princess and her slaves:

Just as a mountain lion trusts its strength, and

beaten by the rain and wind, its eyes burn

bright as it attacks the cows or sheep, or wild

deer, and hunger drives it on

to try the sturdy pens of sheep—so need

impelled Odysseus to come upon

the girls with pretty hair, though he was naked.

Hunger is cruel; it drives the body toward survival. Odysseus tells the Phaeacian king, Alcinous:

The belly is just like a whining dog:

it begs and forces one to notice it

despite exhaustion or the depths of sorrow. My

heart is full of sorrow, but my stomach is

always telling me to eat and drink.

*

Albatross are far older than humans on the Earth, descendants of the dinosaurs. They evolved over thirty-five million years into finely honed gliding beings with bills curved to hook prey. The Laysan albatross mostly spears squid, but it also collects floating chunks of pumice and wood with fatty, nutritious flying fish eggs attached. Bits of plastic gather in the currents along with stone and wood, and the albatross picks them up.

Like other birds, the albatross regurgitates what it can’t digest. Before it fledges, the chick sheds weight by coughing up a cigar-shaped lump called a bolus filled with squid beaks, stones and, increasingly, plastic. But plastic doesn’t wear smooth in the waves. It retains its shape or breaks into shards, and sometimes the bird can’t get it out.

*

A new image of an albatross has etched itself inside my brain. This one comes from the scientist Carl Safina. He traveled to Midway, an atoll in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands about fifty miles southeast of Kure. Midway is home to the world’s largest Laysan albatross colony: 600,000 breeding pairs.

In his book Eye of the Albatross, Safina describes watching an adult glide in from the ocean, pick out its chick among the crying and begging thousands, and open its bill to deliver food into the thrusting, frantic mouth. “The adult hunches forward, neck stretching, retching,” he writes. It delivers several chunks of “semi-liquefied squid and purplish fish eggs.”

The adult continues to retch and the chick to beg for more, but nothing comes. Then Safina sees the tip of a green toothbrush emerge from the bird’s throat. The bird tries several times to get the toothbrush out with no success. It gives up and wanders off.

A new image of an albatross has etched itself inside my brain.An albatross can live for sixty years. A plastic toothbrush can last—no one knows how long. Five hundred years? A thousand? How long can an albatross live with a green toothbrush stuck in its gullet?

*

O happy living things! no tongue

Their beauty might declare:

A spring of love gushed from my heart,

And I blessèd them unaware:

Sure my kind saint took pity on me,

And I blessed them unaware.

Awed by the beauty of the sea serpents, the mariner in Coleridge’s poem prays, and the albatross drops from his neck and disappears into the ocean. The bird is not a burden. It never was in the poem; it never had that physical heft. The albatross around the neck is a mark of guilt.

The mark remains, even after the body of the bird is gone. The sailor is compelled to spend the rest of his life telling others what he has seen.

__________________________________

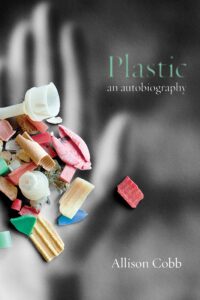

From Plastic: An Autobiography by Allison Cobb. Used with permission of Nightboat Books.