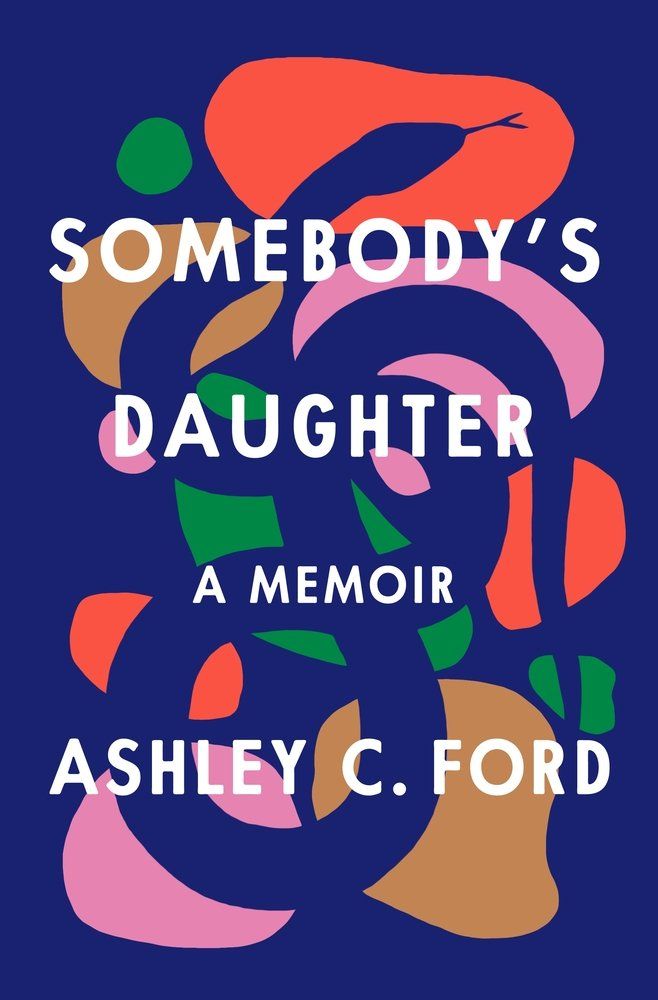

When Ashley C. Ford logs on to Zoom to talk about her much-anticipated memoir, Somebody’s Daughter, it’s from Indiana, where she lives with her husband and dog. In some ways, that’s a surprise because she’s been such a celebrated figure in the New York media, landing on the Forbes “30 Under 30” list in 2017, along with receiving piles of other accolades for her writing and interviewing. But Indiana is where she grew up, and it’s where she wants to be now despite the challenges of her childhood.

Somebody’s Daughter chronologically details her growing up and slips us into the child’s point of view. Grown-up Ashley doesn’t explain how poor her family was; child Ashley shows us. She lives with her mother and brother in a studio apartment. She knows her father is in prison but doesn’t know why. She spends time with her grandparents and witnesses a different kind of kindness (but also cruelty) than she experiences at home. As she grows older and understands things more clearly, she’s often at risk from violence at home and outside it.

While she longs for her father, idealized and absent, she grows up surrounded by extended family but is basically unparented. Her narrative shows how far she’s come in treating gently now those who treated her harshly then, including her mother.

The New York Times writes that the book, which is published by Oprah’s imprint at Flatiron Books, “is the heart-wrenching yet equally witty and wondrous story of how Ford came through the fire and emerged triumphant as her own unapologetic, Black-girl self.”

Ford talked to Shondaland about her book, social anxiety, what it’s like to interview someone like Serena Williams, how the publishing industry can do better at finding stories like hers, and what question she’s never asked that she’d like to be asked.

CAROLYN KELLOGG: Congratulations on the book! What does it feel like now to be at the precipice of it being out in the world?

ASHLEY C. FORD: It is exciting and terrifying. You know, it’s the goal. I didn’t write it just to have written it and have it; I wrote it hoping people read it. And then they would be able to find something useful in it, in some capacity. I’m realizing, as we get closer, that my expectations for my book — I think I tried to temper them so much — I probably didn’t do enough to prepare myself for some of the reactions to it. Which has all been good. That’s the weirdest part. I just wasn’t prepared for some of the people who read it to like it as much as they did.

CK: You’re doing an online book tour being interviewed by some great people, including Oprah.

ACF: When my book proposal was with different publishing houses, my publisher, Flatiron, one of the things that was the heart of their offer was that they had sent the book to Oprah. Oprah has a publishing imprint with them, and apparently she liked my book enough to buy it. As I was writing it, as all this was happening, I know that my publicity people were talking with her people, and my expectations were really low, and not because I didn’t think she would like it or wouldn’t want to support it, but really just because I’m like, she’s busy. She’s busy! And this is just me coming out with this debut memoir out of nowhere. She’s already said that it can be on the Oprah imprint. That’s already a boon for a book like this. Like, what else could she possibly do? What else could I expect from her? When they asked, how do you want Oprah to be involved? I’m like, is adoption available? And it wasn’t. So the next best thing I wanted was I would love to be in conversation with her. I want to know what she thinks about the book. I want to know what questions she has about the book. If not the best, she’s one of the best interviewers in the world. To be interviewed by her is this honor; it’s the dream I was scared to dream.

CK: Your book pulls off a tricky mix. Early on, you embody your childhood perspective without bringing adult knowledge into it. Later, there’s a kind of wholeness with the way that you write about your subjective experience that is generous to people who might have harmed you, like your mom, say, which seems really informed by therapy. How did you balance that in writing?

ACF: I mean, I had to do a lot of therapy to finish the book. I had to do a lot of therapy. At the point that I started writing it, I had been in therapy for a few years. And I really felt like there’s a lot going on in me, but I think I understand where it comes from, or at the very least I think I understand that these things don’t make me a terrible, no-good, unworthy-of-love person. I think I understand that. That’s where I started the book, and that’s why the book took me 10 years to write.

When I was growing up, there was a great belief in adults that kids just didn’t experience painful emotions the way they did. They confuse a child’s inability to sometimes name and express emotion with that emotion not being present in the child. I wanted to very clearly convey how aware I was as a child, because I was. I was extremely aware, and I was confused at times, and I was noticing patterns and picking up on those patterns. It was a lot. It was a lot. And the worst part about it was that I wasn’t allowed to talk about it. I was not allowed to talk about my sadness. I know that if I said I’m mad, or I’m sad, or something like that to my parent at that age, her reaction would have been one of extreme defensiveness and possibly physical violence. And so you have to ask yourself as a child, is it worth it? Is it worth it to say that I am angry or say am I willing to fight? Because that’s really what it is. Am I willing to fight or be beaten for expressing this emotion? So, it’s dealing with all of these emotions, all these feelings, all these experiences with child logic, which isn’t accurate but feels real because you’re a child, and nobody is telling you anything different. I wanted to write out what that felt like and how much that hurt.

CK: You write about being an adolescent and spending time after hours at your old school seeking out teachers. Was school a safe space?

ACF: Well, first of all, school was a place where nobody could hit me. School was a place where, if somebody hit me, they were going to get in trouble, which felt very free to me. That no matter what I said or what I did, nobody was allowed to hit. That was amazing. And then part of the reason why I titled the book Somebody’s Daughter is that part of the point of the book is found family — friends, boyfriends, teachers. These people, in a lot of instances, were filling in real parenting gaps that my biological parents could not or would not meet. My boyfriend taught me how to drive. My college roommate taught me how to cook.

CK: Your high school boyfriend talked you into applying to college.

ACF: Yes, he did. My mom never asked me if I applied to college. She was never like, are you doing that? Have you done that? Did you take the SAT? She wouldn’t know. My mom wanted me to graduate high school because she would have been embarrassed if I had not graduated high school. Anything beyond that just wasn’t really the case. And so my encouragement always came from teachers or friends or my boyfriend.

CK: Yet I think you’re really fair to your mother. If there’s anger about your experience, you’re not expressing it on the page. You’re just showing what happened.

ACF: Yeah. I think that is partly because, like, that is how I feel about my mom. Like, it’s not that I’ve never had any anger toward her. It’s just that I processed it, you know? And, in a certain sense, I processed my anger at my mother, or toward my mother, for me. It’s not about her at all, really. It’s about me. I needed to process that anger. I needed to get that out of my body and out of my head. That’s what I needed. And, you know, for all the ways I wish my mother would have taken care of me differently, I can take care of myself in all those ways right now. I think what I tried to do on the page, and being fair with my mother, is like the places where it may seem like my anger is missing — you know it’s there. You’re a smart reader. Do you think this happened to me, and I walked away like, oh well. I walk away in my mind, thinking, that bitch! In my head, that’s what I was absolutely thinking. Even as I internalized, even as I then turned around and said, this is your fault, Ashley, because why did you even try to talk to her? All of that stuff, I was really good at turning my anger at her into anger at myself. So that’s why there’s not a lot of anger toward my mother in certain places on the page; you see it turn inward, because that’s what happened. I was mad, but I found a way, always, to turn it inward. And that’s why processing my anger is not about her. I love her. I want her to be well. I want her to do well; she’s my mama. You know what I mean? But at the same time we don’t have the kind of relationship you’d see in a Hallmark movie. Sometimes it is hard to explain to people that it is more distant than you would be comfortable with, but it works for me.

CK: If you don’t want to talk about this, just tell me, but I want to ask about the chapter in the shed [where Ford writes about sexual assault]. It’s horrifying, and I’m sorry it happened to you. You write with such precision about the experience of dissociating from yourself. How did you capture that?

ACF: Well, I think part of the reason why I was able to write about it the way I did is because I still experience it. It’s not something that’s gone for me. It’s not something that went away. I honestly think that once you do it, once it’s a practice of something that you do, even in childhood, it’s like a place you can always go. I have to be able to have more control about when I slip into that place. Is it a choice to slip into that place? Like, am I going — you know what, actually, I’m dissociating for five minutes. Is that what’s going on? Or is it, I find myself there, which is a little bit scarier.

CK: Like as the result of trauma or anxiety?

ACF: As a result of anxiety, triggers. There were things that it took me years to realize were triggers from my trauma and not just weird things about me. There were some things that are obvious — like, I could not deal with, like, crashes or things breaking or loud sounds. If something happened like that, [snaps] gone. I’m just gone [snaps again]. There’s also, you know, intimacy — you know, physical, sexual intimacy — and realizing that, for a good portion of my life when I was intimate with somebody, I was dissociated. Then getting to a place where you’re like, I don’t want to do that. But then what does my body want when I’m not dissociating? What does my brain want? Having to figure those things out. You can only figure that out if you go into it. I never knew why the cold made me angry. I spent years, whenever I got cold — I mean, a cold office, a cold classroom; I hate air conditioning. I know now that the circumstances of what happened to me trigger that.

CK: You’ve done so many different things, and have often interviewed people. What do you get out of those in-person interactions?

ACF: The interviewing is actually really easy for me. I don’t get, necessarily, starstruck. Even if I’m nervous, a lot of times my nervousness is the same nervousness I have around everybody. I have social anxiety. I think one of the things that comes from my social anxiety, where I find some power and some control in that, is that I’m really good at soothing other people’s social anxiety. Because I’m already there; I’m already in it. So you don’t have to worry about impressing me. You don’t have to worry that I’m here to get you or anything like that. We’re not doing that. We’re having a conversation; we’re having an experience. I’m going to go write the story from the perspective of the experience that I have with you right now.

The piece that I wrote about Serena Williams for Allure, the thing that people always say to me about that piece is I knew I was going to like it when you said that you were embarrassed of your socks. Which was true because I showed up not thinking about the fact that I was going to walk into her home, and I wore Pac-Man socks! I had all these Pac-Men all over my feet, and I was up immediately like, oh no. Serena Williams will be like, who is this reporter with these Pac-Man socks? At the end of the piece, she compliments me on my socks. And that story is as much about how I see her as how she then turns around and sees me. I think that’s relevant. I think that’s kind of what we want to know, sometimes, about these people. We know how we see them already. I think a lot of people think, what would that person think about me if I was in that room? Would they talk to me? Would they have an opinion on me? I like to bring all that into it and build a story. And sometimes it works out, and that makes me happy.

CK: What’s a question that you have not been asked that you would like to be asked?

ACF: My first major in college was fashion, and I never get asked about fashion. I also never get asked about boy bands, which is also a huge subject of interest for me, specifically ’90s boy bands.

CK: Um, okay. ’N Sync or Boyz II Men?

ACF: That’s so great. And I would absolutely choose Boyz II Men.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Carolyn Kellogg is a former books editor of the Los Angeles Times; she can be found on Twitter @paperhaus.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY