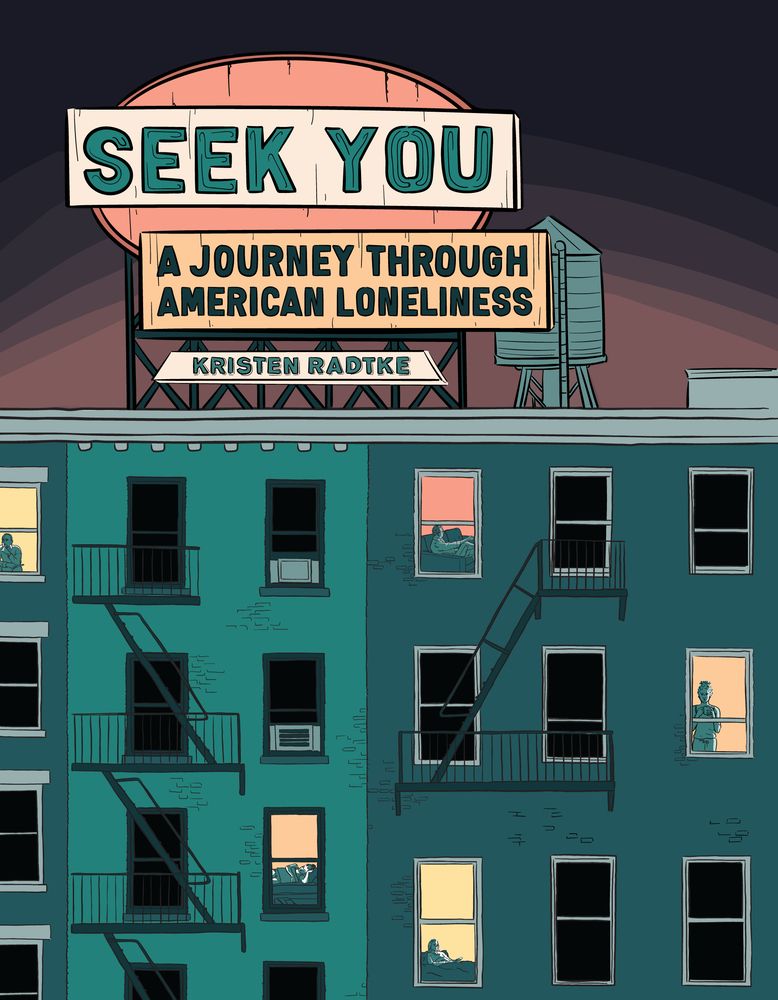

As art director at literary magazine The Believer and contributor to publications like The New York Times and The Atlantic, Kristen Radtke is an illustrator and writer whose work has a wide reach. Also the author of 2017’s Imagine Wanting Only This — about what and who is left behind after death — Radtke is here with another ruminative book of graphic nonfiction titled Seek You: A Journey Through American Loneliness.

In it, she uses her own experiences with loneliness as a jumping-off point to explore the meaning of this misunderstood and universal emotion. Through interviews with friends, research into scientific literature and discourse around loneliness, and personal story, Radtke paints a fascinating picture of what it means to be lonely and connected in a country where individualism is highly valued. She explores tropes of cultural narratives like the lone cowboy and the isolated princess; how changes in technology over time influence people’s perception of how we interact with one another; health outcomes of loneliness and how they are different from living with others; and American psychologist Harry Harlow’s disturbing experiments involving separating and isolating infant monkeys.

In braiding these threads together, Radtke paints a compelling and multifaceted picture of how loneliness exists and is experienced in the U.S. Though the book doesn’t touch much on Covid-19, it is only more prescient because of the widespread isolation induced by the pandemic.

Shondaland spoke with Radtke about Harlow’s horrors, what surprised her about her research, and the importance of stories in connecting with one another.

SARAH NEILSON: What was the impetus for embarking on this exploration of American loneliness, and how did the questions you were asking about it change over time as you were working on the book?

KRISTEN RADTKE: In 2016, I did this illustrated series about loneliness where I was drawing people alone in public settings, and I thought that that was as far as it would go. I thought I was just going to do this illustration series, and that would be it. But then I started questioning loneliness in general and what loneliness is, and what loneliness does to us, and got kind of fascinated by it. I realized that I was writing about loneliness for a long time before I knew that I wanted to make a book about it or that I was writing about it at all. Over time, I think my understanding of loneliness changed an enormous amount because I learned what it actually was. I thought of it as just a bad feeling, like feeling sad or depressed, but I didn’t understand that it was actually a psychological state that has roots in our biology.

SN: What was your research process like for gathering the historical and scientific information and the context for the book?

KR: I just kind of followed my interest. You read one book, and then that makes you think about another thing, and then you pick up five more books, and then all of a sudden you’re just deep into this subject area that you didn’t necessarily intend to get into, which I think was the most fun. For me, the most fun part of a project is just learning. It was very unexpected the places that I ended up going. I didn’t anticipate doing research about much science at all. Certainly, I didn’t expect to be writing about princesses or cowboys and stuff like that. Research just brings you to all these different interest areas.

SN: I wanted to ask you about the cowboys and princesses and those gendered historical narratives; what did you find most interesting or compelling about the ways that gender and loneliness interact?

KR: One of the things I write about in the book is that male TV protagonists, if they’re lonely, they get to be lonely-cowboy archetypes, like all of our antiheroes. All the Don Drapers of TV are just like a regurgitation of a sort of cowboy Hollywood trope. I think that’s really interesting because it’s rare that women get portrayed that way. Certainly, there are exceptions like Mare of Easttown. There’s certain characters that get that sort of cowboy treatment, but even then they’re portrayed as more tragic, I think, than men. With women, their loneliness is often portrayed in a makeover romcom kind of way. As soon as they find a man, everything is fixed.

SN: You explore the idea of how changes in the technological landscape over time influence both real and perceived loneliness. Can you talk about that a little bit and what you learned about the vocabulary and paradigms of conversations about technological change?

KR: As I was doing this research, I realized that every time there’s a new technological advancement — like the internet or cell phones or even radios and TV or telephones, regular, old rotary telephones — there’s always this big outcry of like, “This is going to change everything. This is going to ruin the way we interact with one another.” And I think in some ways the internet is definitely changing the way we communicate and is perhaps damaging it in certain ways. Obviously, there’s been a lot of collateral damage with the internet in terms of news and things like that. But I think, in general, some of that stuff is a little bit overstated because it’s just a new tool to enact the same thing we’ve always been thinking or feeling. I don’t think the internet has brought forth problems that didn’t already exist. It may exacerbate them, but the internet is always kind of an easy scapegoat when we’re talking about disconnection. But for a lot of people, the internet is a major source of connection.

SN: I want to touch on what you said about the internet’s collateral damage because it ties in with this idea of trust and mistrust in America specifically. It’s so important for bonding on an individual level, but how does the large-scale mistrust in American society and politics, which is maybe sometimes necessary, filter down and influence our relationships or our loneliness?

KR: I think skepticism and distrust are different things. I think it’s very important that we are skeptical of what elected officials are telling us and things like that. But I think that trust is very essential. It’s the basis for forming bonds. We can’t have significant, meaningful long-term bonds without some level of trust. If you look at research that’s been done about people who live under totalitarian regimes or people during the Cold War in [the Soviet Union] who felt like they couldn’t trust their neighbors because anyone might sell them out or be a member of the secret police, the levels of loneliness just go sky-high. You can’t trust the people you’re supposed to be able to trust, like your neighbors. So, I think that distrust of one another, and also the more isolated we are, the more likely we are to assume the worst in people we don’t know. Without making too generalized comments, if you look at places that vote very conservatively, they’re more isolated communities.

SN: You included a lot of information from several different scientific studies around loneliness. The big-picture takeaway for me was that people experienced different degrees and layers of loneliness in different situations and contexts, which makes it really complex to study and understand. Was there anything in particular that either surprised you or most interested you in the scientific research that you read?

KR: I was fascinated by all of it. Like the way in which when we’re lonely, we have weaker immune systems. The fact that people who are chronically lonely die sooner. What I think is really interesting about that is that scientists often attributed that to, for example, people who live alone are more likely to die prematurely than people who live with at least one other person. For a long time, scientists were just like, “Oh, of course, there’s no one there to call for help if you’re hurt,” which is what I assumed at first too, but then over time, the more they studied those numbers, they realized that the distinction in death between people who live with others and people who live alone is too great to attribute it to things like accidents or not getting to the hospital on time if you have a fall or a heart attack or something. I think things like that are quite startling.

SN: Yeah. For me, one of the most striking parts of the book was all about Harry Harlow and his studies on monkeys. I found it extremely disturbing. It seems like it was so heavily fueled by his own loneliness. But he also used the word “love” to describe what he was doing. Was there anything that struck you most about Harlow and his experiments, and in what ways do you think reading about his work made you think about the intertwining of love, loneliness, and attachment and how those things are maybe not the same?

KR: I think Harlow is very interesting because obviously he was doing horrible stuff. He was very sadistic and did torturous stuff to animals. But it was an interesting experiment to try to write about someone who was doing such horrible things with empathy and to try to understand what his mind frame was, which is not a way of condoning or excusing the behavior at all because it was horrific. But I think it’s very interesting that someone like him was one of the first people to publicly, in the scientific community, talk about love when the common word in science at the time was proximity instead of love. I think it’s fascinating that someone who sort of proclaimed that love was real seemed incapable of showing it to animals or really to the other people in his life, because he was horrible to his wife.

SN: One of my favorite lines in the book reads, “Stories are how we draw ourselves closer to one another, and how we remember, and sometimes how we reshape.” What stories have been important to you, both in creating this book and in navigating loneliness in your own life?

KR: It’s a really interesting and very difficult question. In one of the parts of the book, I asked friends, “What’s the loneliest you’ve ever felt?” I was really amazed by the stories, how specific they were and how much people could feel them. Some people would cry when they told me the stories, even if it was something that happened a really long time ago. I think there is a way in which we can try to reclaim moments by telling stories about them. Certainly, that’s true for trauma. A way we can take charge of it is by telling it from our own perspective, and when people witness it, it sort of makes it real or validates it for us. To me, I talk a lot. I like to talk things through. Really the only way I can even figure out the way I think or feel about something is by talking about it with my partner or with my friends and sort of seeing it reflected back. So, it’s hard for me to think of a specific story other than to say all of them.

Sarah Neilson is a freelance writer. They can be found on Twitter @sarahmariewrote.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY