When I say that Aaliyah’s “Are You That Somebody?” music video was responsible for my sexual awakening, I’m embarrassed by my own rehearsed performance of heterosexuality. But it’s true. During the summer of 1998, the only thing on my 11-year-old mind was when MTV, BET, or, in a desperate fit, VH1 would cater to my desire and play the only video that meant anything to me at the time. I usually wasn’t waiting long; “Are You That Somebody?” was in heavy rotation, as the second most-played video on BET during the first week of July in 1998, then the number one most-played video on MTVin mid-September that same year. I was able to see it virtually anytime.

I made a show of my love for the video, at least when my parents weren’t around. I’d talk of how I wanted to marry Aaliyah; I’d writhe with excitement during the moments where her impossibly flat stomach was onscreen, twisting in ways I was just coming to understand were sexy. I’d say that what I was really waiting for was the end of the video, the flamenco dance breakdown, where Aaliyah dons her skimpiest outfit, the full length of her bare legs exposed for my gawking. I wanted her, to be sure, but I also wanted it known among my peers that I wanted her.

Aaliyah wasn’t my first crush. That distinction belongs to Chilli from TLC. And “Are You That Somebody?” wasn’t my first brush with sexualized imagery, or even the most explicit. Adina Howard’s “Freak Like Me” had come out years before, along with the aforementioned TLC’s “Red Light Special,” among other, more raunchy fare coming from the world of hip-hop.

But Aaliyah was my first real crush after learning what sex was. I was only four when I was crushing on Chilli—a crush then amounted to wanting to have an extra-long hug, perhaps having my head pet gently. In ’98, I knew that there were more possibilities, and Aaliyah was the first to arouse the desire in me to explore them all. Those lips, those eyes, those legs, that voice …

Here I am, again, performing. Because I’m not here to recount the details of a preadolescent crush—or at least, that’s not the part of my pitch that was of most interest to my editor. But I needed to clear my throat a few times, because I’m still afraid to say what it is I came to say.

I wanted to be Aaliyah.

It’s not something I would have had the language to express at the time. It’s something I’m still trying to find words for now. But a couple decades of reflecting on my attachment to that particular video has opened up the part of myself that wasn’t only feeling the desire to have and hold, but the envy I felt for who Aaliyah got to be.

At that age, I would have said that I wanted to be Michael Jordan or Penny Hardaway or Allen Iverson—tall, muscular, perfectly masculine men engaged in a perfectly masculine pastime of dunking on their opponents and pounding their chests in accomplishment. Outside, on my driveway basketball hoop, in front of my parents, and neighborhood kids, that’s who I emulated. In the privacy of my bedroom, I rolled up my shirt and tried to wind and contort my abs like Aaliyah was doing—never standing up, lest someone walk by and seek explanation. I would lie on the floor and furtively copy what I saw in a way that could be corrected if anyone saw me.

I knew what was expected, who I was supposed to relate to. When the video came on in mixed company, I would mimic Timbaland’s Southern gravel and say, “Can y’all really feel me?,” until Aaliyah began her seduction, then nod along until Timbaland came back to rap his verse. I would bounce my shoulders and flex my arms and try to keep up with the switch to double-time flow in a way that was appropriate for my gender identity. I reassured everyone that I was normal.

I reassured myself by saying that what I wanted from Aaliyah was sex. I had already been branded shy and sensitive, and I knew these weren’t normal or desirable things to be. I couldn’t risk also being the boy who wanted to be like a girl.

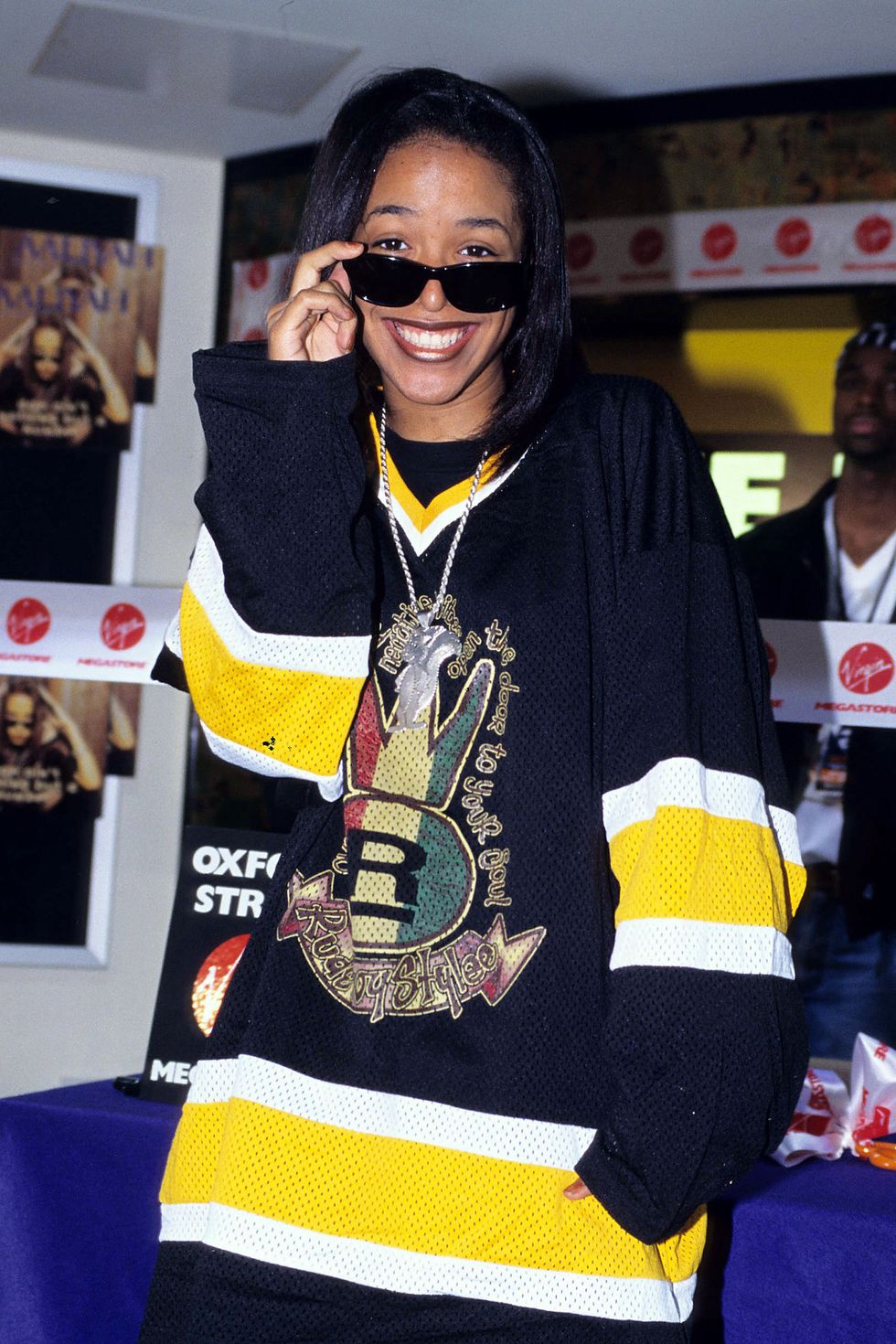

This is what I envied in Aaliyah: She got to be a girl who sometimes dressed “like a boy.” It was in style then. When she debuted in 1994, under the guidance of the (alleged) predator R. Kelly, Aaliyah looked like a long lost member of Jodeci. She wore oversized jeans, combat boots, leather vests, bandanas, and shades. She didn’t pioneer this look, as Mary J. Blige and others had already carved out the space where female R&B singers adopted male hip-hop fashion and posturing, but there were hardly any hints of girlishness in Aaliyah’s early presentation. She wasn’t like Brandy, who was the same age and debuted the same year, but was very clearly and deliberately presented as a teenage girl. I suspect this was a part of R. Kelly’s grooming, to have a 15-year-old singing provocative, adult-themed songs, to proclaim on the airwaves reaching millions that “age ain’t nothing but a number,” so she might believe that she was ready for their illegal marriage. I’m only speculating.

With her second album, 1996’s One in a Million, Aaliyah’s image shifted toward a late-adolescent feminine sexuality that’s now most closely associated with Britney Spears or Christina Aguilera. She didn’t ditch the baggy clothes altogether, but she started to incorporate items like crop tops and bralettes, and her eyes were no longer hidden behind dark sunglasses. It was playful and sexy in a way that felt more genuine to her.

I think her look reached its final form in the “Are You That Somebody?” video, and I have longed for what I saw. I didn’t want my body to look like hers, but I wanted—want—to feel like I could move and adorn my body as freely as she did. I wanted to roll, to sway, to entice, to wear sequins and lace, to pair men’s bottoms with women’s tops, to put on eyeliner and sneakers.

I’m saying this in 2021, when this isn’t unheard of for cis men to do, and yet I still feel restrained. I feel the pull of “normal,” of what my mother’s reaction would be. It’s not something that I even feel compelled to make into my day-to-day. I’m fairly comfortable with my gender expression as is, while noting that part of that comfort comes from the privileges it affords me. I won’t be assaulted or denigrated or chastised or insulted for my walking down the street looking the way I do now. I am protected.

The desire hasn’t faded though. I allow myself moments behind closed doors, in intimate space, with a trusted partner. My current girlfriend didn’t shy away when I told her; she embraced it with zeal and made me feel beautiful for the first time ever. It was one of the few times I’ve cried from joy.

But I am pained for the boy I was who didn’t get to play. When my father alerted me the night of August 25, 2001, that “that young singer, Aaliyah, just died in a plane crash,” in his detached manor, I mourned but couldn’t say all that I was mourning. I would have said that I lost a crush. I did. But I lost an opportunity to one day ask her, Can you teach me how to be free?

Mychal Denzel Smith is the author of Stakes Is High: Life After the American Dream and the New York Times bestseller Invisible Man, Got the Whole World Watching. His work has appeared in the New York Times, Washington Post, The Nation, and elsewhere. He lives in Brooklyn.