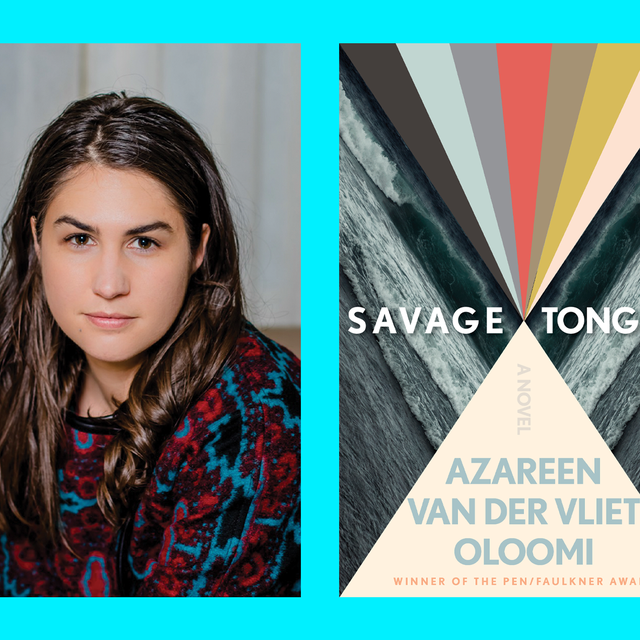

Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi is a celebrated writer whose previous novels — 2018’s Call Me Zebra and 2012’s Fra Keeler — won her multiple awards, including the 2019 PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction and the 2015 Whiting Award, respectively. She is Iranian-American and has lived in Italy, Spain, Catalonia, United Arab Emirates, and Iran and is the founder of a lecture series called “Literatures of Annihilation, Exile, and Resistance.”

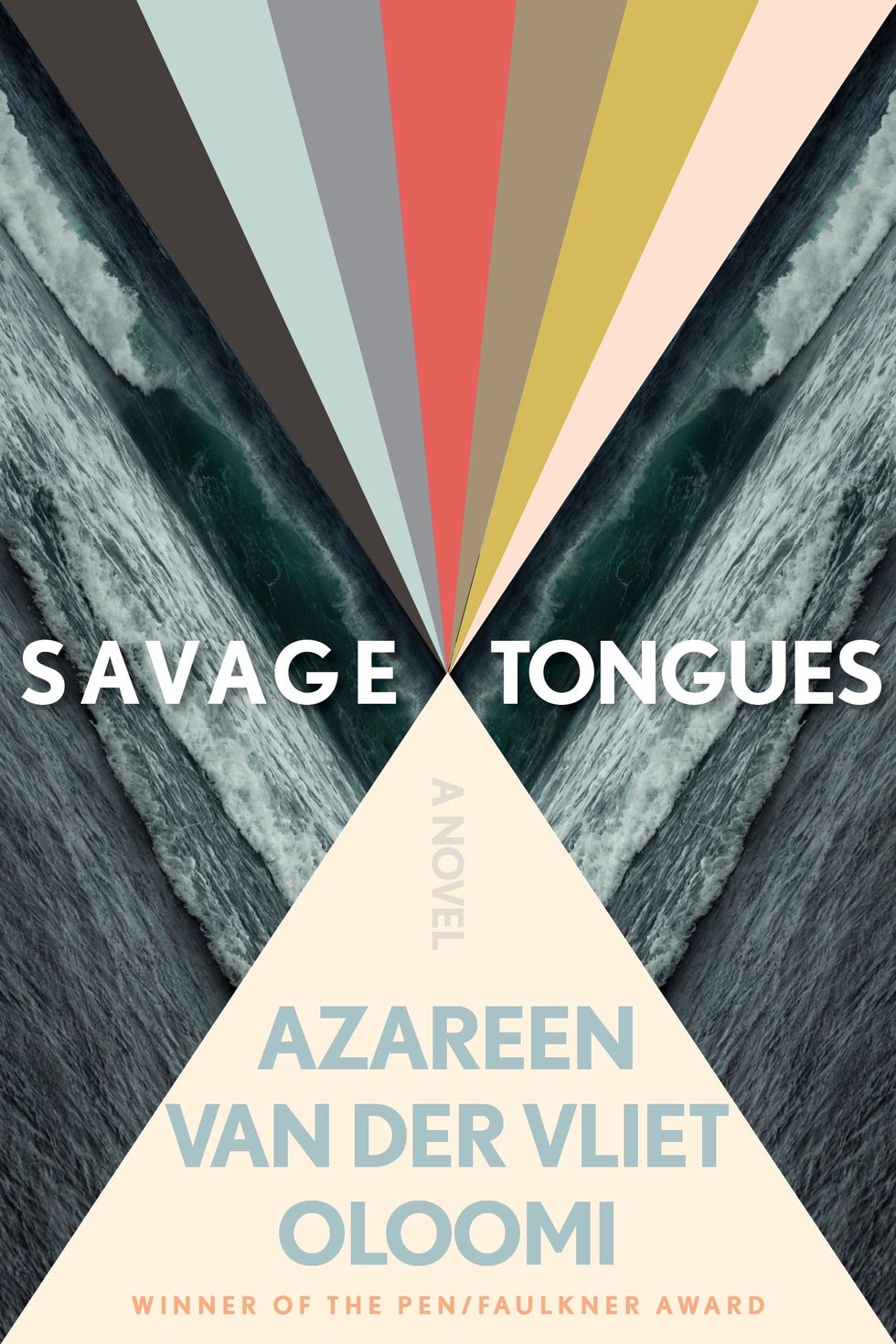

With her new novel, Savage Tongues, Van der Vliet Oloomi delves into these ideas and themes with the story of Arezu, a 40-year-old Iranian-British writer who returns to the apartment in Spain where she had an affair with her father’s then-40-year-old step-nephew as a teenager. When her father dies, Arezu inherits the apartment and is accompanied by her best friend, Ellie, an Israeli-American scholar and professor dedicated to Palestinian liberation, to clean it out. As the two clean, they engage in their ongoing relationship of intellectual and spiritual connection and witnessing each other’s movement through trauma and through life. Savage Tongues is a story of healing and intimacy between friends, especially among their queer friend group, who are the strongest family both women know.

Shondaland spoke with Van der Vliet Oloomi about how nations shape identities, queer relationships, the intersections of geopolitical and interpersonal violence, and complicated questions of sex, gender, agency, and morality.

SARAH NEILSON: One of my favorite things about this book is how well it captures the way friends can witness each other, and how important that is. How would you describe the relationship between Arezu and Ellie and its central role in this story?

AZAREEN VAN DER VLIET OLOOMI: It was my intention for it to be very female-centered and queer-centered. I think that there’s a way in which Arezu and Ellie bear witness to each other. They never flinch when they’re being exposed to one another’s traumas from their deep pasts, nor the ways that their traumas get replayed as their identities evolve and they acquire new aspects or dimensions of their character through their professions or their relationships. They’re both also very intellectual characters, and they’ve been in this deep intellectual conversation with one another that has some spiritual undertones, about how to move through grief and how to bring some joy into the process of bereavement rather than to think of it as something that is finite and that needs to be dealt with quickly and then compartmentalized or moved on from. They really understand the ongoing nature of witnessing our own trauma over and over again as we evolve. They both also have very complicated personal identities and political identities.

Ellie comes from a very Orthodox family, but she’s no longer practicing. She leaves home in part because she’s queer, but she also resists some of the covenants and some of the restrictions put on her gender, and some of her own sexual trauma as a result of being homeless or cast out of her community. Over time, she comes to understand her own politics against the occupation of Palestine as interconnected with her queerness and has a pretty articulate way of understanding discourses of domination and the ways that domination operates in different arenas of her life, whether it’s a kind of patriarchy or heteronormativity that both Arezu and Ellie perceive as extensions of nationalism and colonialism.

Arezu is Iranian, she’s British, she’s American. So, she’s both oppressed and part of the oppressor and has these warring factions inside of her psyche and her body that I obviously share with the narrator. So, for me, it was a way of working out and integrating parts of myself that live in conflict with one another. And I think, against all odds, Ellie and Arezu understand each other perfectly.

SN: A lot of your work explores how geopolitical violence intersects with trauma and interpersonal violence, and how that shapes individual lives and physical bodies in obvious and subtle ways. How did you approach exploring that theme in Savage Tongues?

AVVO: I think that’s been a difficult part of the novel for some reviewers to really grasp, the ways that these things intersect with one another. It’s such a complex question to unpack. The way that Arezu sees and examines her consensual but deeply abusive relationship with Omar — consensual with an asterisk because it’s not entirely consensual, so it’s already in this kind of ambiguous zone — she’s trying to take a step back to widen the aperture, to understand the web of enablers who made way for this abuse to happen. Which includes both of her parents, her father through neglect, and her mother because she is stuck in a state of helplessness even though her intentions are good. And once she takes a step back to understand that, then she realizes that her mother is also homeless and is no longer rooted in her cultural points of reference, and the way that she’s parenting her children only leads them further into danger and lack of safety. They leave Iran because they feel unsafe, and they come to America, and the brother is attacked by a skinhead.

Arezu witnesses that, which is actually based on a real-life event that happened in my family. And the witnessing of that event and the lack of safety when you’re coming somewhere else to look for safety, and then you realize that you’re racially or ethnically being mapped onto the landscape in ways that you couldn’t have foreseen, it complicates Arezu’s understanding of her relationship with Omar even more because she decides to self-destruct. She sees Omar, feels sexual desire, she’s sexually almost initiated by him and awakened by him, which is part of her agency that she doesn’t want to let go of as a woman. At the same time, she also knows there is some danger there. She underestimates the danger, but she goes into that danger head-on because she has so much survivor’s guilt and confusion around what happened to her brother. So, it’s really about connecting these intimate wounds to these larger historical wounds and understanding that these lives, Ellie’s included, are unfolding and caught inside of these structures that are systemic, that are institutional, and have to do with human rights on a global scale.

SN: I want to latch on to something you said about cultural reference points and the different kinds of ways societies define good and bad behavior, especially as it relates to gender and sex. How does this story complicate ideas of morality and agency around gender and sex, and what draws you to explore that complication in your work?

AVVO: Arezu is really aware of the way that the colonial discourse is a sexual discourse as well. The way that the very oppressive or suppressive Victorian ideal of white masculinity, which is quite repressed and quite tucked in, defines itself as pure by defining Black and brown bodies in the colonial territories as either asexual and emasculated — so that they’re not posing a threat — or out of control and hyper-sexual and unable to control their impulse and therefore a danger to the white woman. We see the way that the white psyche, even in the American landscape and the British landscape, defines its ideals of purity by standing in opposition to something that is impure or savage or barbaric, and the title of the book is really playing with that and the erotic dimensions of it.

One thing that I think about a lot is how that state-sanctioned violence and colonialism is a form that generates identity. It doesn’t just suppress identity. Arezu is a difficult, risky character to write because she’s very intellectual and is trying to figure out how her own desire for Omar was informed by the fact that, on the one hand, she was told that he’s dangerous and this animal brown body who would not be able to control himself. On the other hand, emotionally, I think Omar feels safe, like a safe way to explore her desire, because white masculinity she begins to associate with violence.

SN: Can you talk about the meaning of place and how you shape your ideas around it in the book and in general?

AVVO: Place is so evocative for me to write. It’s three-dimensional. It’s sensual. It transports the reader. I think it’s one of the reasons why we read, to be able to inhabit another physical space. [In the book], the apartment is definitely a haunted space for Arezu. All of the ghosts of her relationship with Omar live on in this apartment that’s really a ruin that she then inherits when her father dies. They spend so much of the novel trying to clean the apartment. Every time they clean it, the dust seems to resettle almost immediately. So, there was a symbolic aspect to that — it’s like a conceit for the trauma but also the way that our consciousness is entirely shaped by space and landscape and how parts of our identities really live on in certain spaces or get left behind in certain places.

I was very interested in a kind of somatic journey of return to the site of the trauma in order to reconstruct it for herself so that in that reconstruction, in that physical return, she’s able to actually find the language that she needs to catalog what happened. That physical reencounter with those items that were so personal immediately allows her access to her younger self, as a 40-year-old woman, that she didn’t have before because she was cut off. It’s like bearing witness from the future to a part of [her] in the past. And she doesn’t go back alone; she goes with Ellie. By the end, there’s three of them — her younger self, herself, and Ellie.

SN: In what ways is this a queer story, and how is queer resilience and resistance built into its narrative?

AVVO: The friends that are the core of the story. They’re each other’s chosen family; they’re each other’s queer family, so in a lot of ways the novel is also looking at what does the conversation around trauma and healing look like when it’s being held by queer bodies and bodies of color and by queer family? There’s four characters in the book — Sahar, who is queer Palestinian; Ellie, who’s queer Israeli-American Jewish; the narrator, who’s pretty queer but in a mixed-orientation marriage; and then Sam, who’s from the south and has transitioned. And the recovery journeys that they go on with each other, the level of commitment that they show each other in their healing processes around political trauma, sexual trauma, displacement, I think is the most extraordinary part of the novel. They’re the real love story. It’s not even so much about Omar. It’s about the forever journey of healing and the way that these queer friends are there to witness that without a time line. It’s just this deep conversation that they know they’re going to be in forever. It’s a novel about post-colonial healing.

Sarah Neilson is a freelance writer. They can be found on Twitter @sarahmariewrote.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY