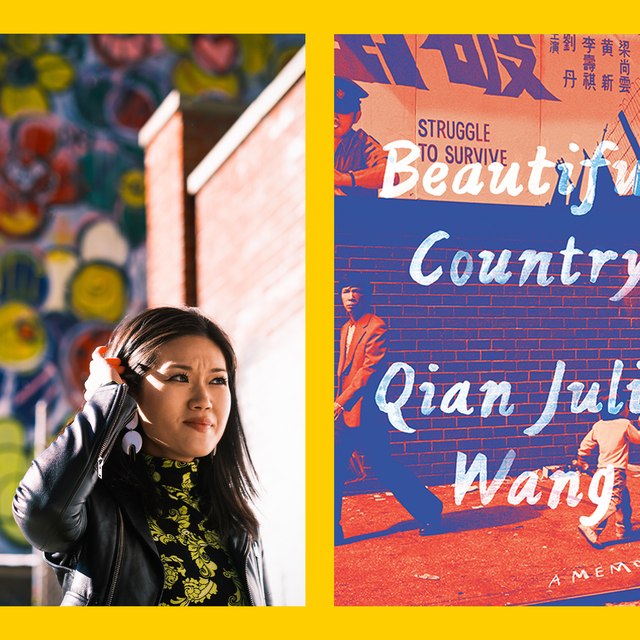

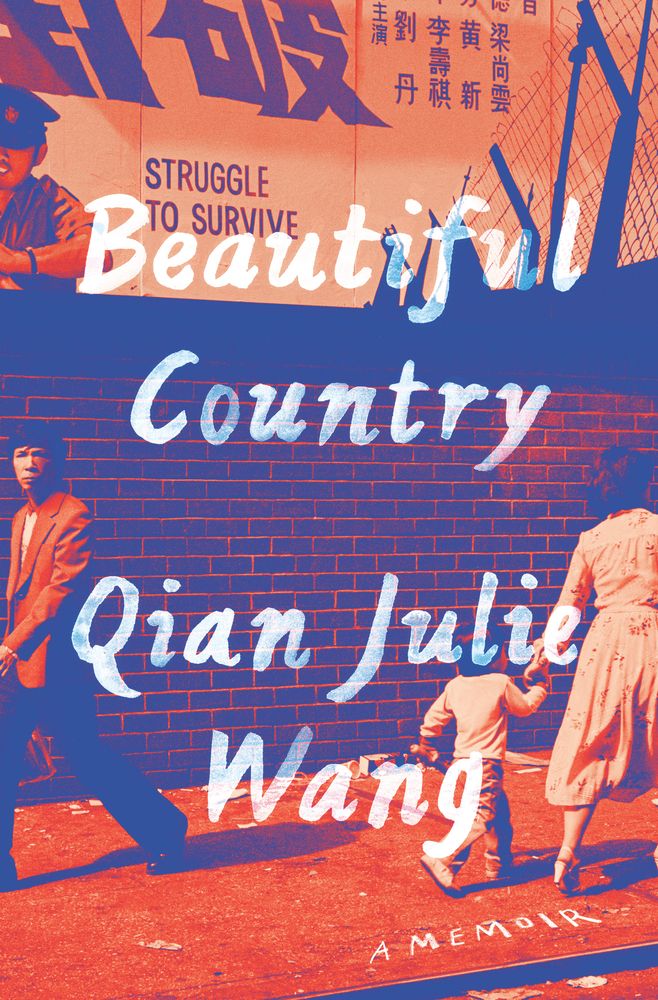

Reading Qian Julie Wang’s debut memoir, Beautiful Country, you wouldn’t know it’s her first book. A graduate of Yale Law School and currently a litigator and managing partner of Gottlieb & Wang LLP, Wang is also a skilled writer, rendering her childhood in rhapsodic sentences that immerse the reader in her experience. At age 7, Wang moved with her academic parents from China to Brooklyn, where they lived undocumented for five years. During that time, she and her parents navigated school, sweatshop work, poverty, and a lack of access to basic needs like medical care — the trauma inflicted by a country bent on dehumanizing people it deems “illegal.” But Wang’s world was also filled with imagination, love, and discovery, and Beautiful Country vibrates on every level of nuance and storytelling.

Shondaland spoke with Wang over Zoom about education, equity, and her relationship to work, play, and joy.

SARAH NEILSON: How did you access and embody your childhood voice in the book?

QIAN JULIE WANG: It was very difficult at first because these years were years that I never allowed myself to think about or talk about for decades, because my parents and society told me that it had been bad and I would have gotten in trouble if I ever talked about it. I decided to embark on writing this when I became a citizen in May 2016, six months before the election. During the naturalization ceremony, a videotaped President Obama said, “Greetings, fellow Americans.” It clicked for me then how much I had needed to hear the word American ascribed to me, and how it never had been until that point. Then, going into the election and hearing all the discourse, I felt something fundamentally change within me, where I recognized for the first time that I had a profound privilege to be on the other side of the experience and that I was choosing not to think about it and not to speak about it.

For me, that was very much a choice, whereas for the millions of people who are still undocumented today, that is not a choice. After that, I thrust myself into writing. That required a lot of intensive therapy, unearthing traumas and memories that I had shoved into the basement of my mind and of my heart. I looked through my old diary entries; I was very inspired by Harriet the Spy, and I wrote down a lot of mundane details of my worlds in hopes that I might be able to solve some sort of mystery. That mystery never materialized, but it really helped me as an adult to look back and try to place myself in that little kid’s shoes. Once I opened the floodgates and really let myself feel everything, it came back fairly quickly. It was really important for me to share the story from that childhood perspective because I know that some of the horrors of life can be much more palatable when presented to adults through the lens of a child, but at the same time deeply disturbing because this is a child who’s filtering it through and not seeing everything that the adult should. I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou was a North Star in this project. I would say the first year of working on the book was just me in therapy trying to break everything apart and understand what had happened.

SN: What is the importance or role of education, inside or outside of the American education system, in the book and in your life?

QJW: It’s deeply problematic to me when people try to frame my story as the American dream because there were profound privileges that I came into these years of being undocumented with, with the primary privilege being that my parents were able to get a good education in China, however you may define it. I think that kind of background at home cannot easily be supplanted by an external education system. That said, an education system formally, certainly is crucial and is the way that we can ensure that there is social mobility in this country. In New York City, and I’m most familiar with New York City because I practice law here and I grew up here, there’s so much segregation based on the wealth of zip codes and where children are just slotted in based on who they’re born to and how much they make. It is deeply problematic, and it creates this whole system of specialized high schools. Making more equitable access to books and literacy is, I think, number one. It was always drilled into me that literacy was my way out, and that was because I had a dad who was a literature professor, who had read Mark Twain and Dickens, and it was part of why he came here. Also, I knew the way that I could convince people not to ask me about where I was from — if I spoke English perfectly, then maybe they wouldn’t even think about it, and I could pretend I was born here. So, from day one, I knew the books were my salvation. They became that in so many ways, not just in terms of learning English, but also finding a sense of emotional safety in America that wasn’t readily available to me, and understanding the power of storytelling. That’s something that still guides me to this day. The stories that we tell ourselves about ourselves are the most powerful of all, and we have a lot of choice in how we allow society to tell us how to tell our story.

SN: How did your work as a lawyer influence the writing of this book, and vice versa?

QJW: It’s definitely a two-way street. I think litigation really saved me. Coming out of college, I was an English major. If I had all the money in the world, I probably would have become a writer right away because I loved books and that’s where I lived. But I had to think about making an income, and law seemed like a way that I could use storytelling to make a difference in people’s lives and still make sure I could pay off my loans. I always knew that I would be good at the writing and researching part and had no idea how it would be on my feet in the courtroom. I was very fortunate in getting a lot of early experiences that forced me to take on big cases and go into court and speak up. That experience really changed how I think about my story and my right to speak up and share it. If you’re doing a pro bono immigration case, and you’re telling your client, “You have this right. You don’t have anything to be afraid of,” you can’t say that too many times without starting to believe it yourself.

As I started writing this book and then editing it, I was reacquainted with that 8-year-old little girl who found the condensed biography of Thurgood Marshall and Ruth Bader Ginsburg and was reminded of all the reasons why she wanted to go into law, and how, in her mind, lawyers were so powerful. They could choose to do whatever they can for the world. What would that little girl think about me having paid off all my loans and having no excuse anymore to be afraid of being hungry, to continue to work for and represent corporations and billionaires and be in this kind of golden-handcuff situation? I wrote the first draft of the book while making partner. After we finished most of the substantive edits, I made partner, and then it was a fork in the road. Do I want to go down this path, which is just following the momentum of what I’d done with my adult life, or do I want to listen to little Qian and do what she would want me to do?

So, I turned down partnership, and it shocked absolutely everybody in the firm, and I opened up my own firm to focus on education law, civil rights, and discrimination work. When I quit, I was terrified, but every day that has passed since, I don’t know how I ever questioned that choice. This is absolutely what I was meant to do.

SN: Can you talk about your relationship to work in the narrative of the book, or in general?

QJW: I think it was very difficult for my parents to shift their relationship to work. Having been professors in China, their work was mostly intellectual through the use of their ideas and concepts and thought, and we came here, and work became very much physical. It was a physical kind of labor, and that was especially taxing for my mother not just because of her health issues, but also because she was a woman, and the ways that manifested I think deeply, deeply affected her. I mean, they were in their early 30s at the time. I can’t imagine going from being a lawyer to someone who has to work in a sweatshop and a sushi factory and just has to endure.

For me at the sweatshop, it was kind of like play because it was physical. I was just playing with things, and I didn’t really have that concept of work yet. But having had that ingrained early on, in my adult life there is nothing that is too much work for me. It’s interesting because you think about lawyers and litigators as people who work with their minds, but it’s also a huge toll on your body because you’re working 13 to 14 hours straight. When I’m at work, I snap into that hyper-focus survival mode, and I could just go on working forever. It created that route in my brain where I just keep going. Now as an adult, stepping back and having looked at everything in my childhood that led me to interact with work that way, I am now very consciously teaching myself boundaries that my work is indeed intellectual; it does not need to be physical.

SN: There’s a line in the book that reads, “Ma Ma didn’t know it, but she was the reason my imagination burned alive everywhere I went, the reason I saw love in all beings and things.” Can you talk about the joyful, playful aspect of your relationship with your mom and your parents, and how they inspire your creativity?

QJW: I’m just so grateful for that, to have had that as a child and to still have that. It’s less in the book with my dad, but over the years as he’s processed some things and started to move on from the past a little, I see these glimmers of moments where the child comes out. They say you regress to the age at which your root trauma is. I think that is true for all three of us. And for all three of us, it just happens to be around the same age of 7 or 8. So, when all of us have our guards down and the children come out, it’s like the best playtime ever. For a few magical minutes, I don’t even care that I didn’t have a real childhood, however you want to define it, because to be children with your parents right there is just so rare. And my parents have held on to their childhood selves, for better or for worse, more than any adult or older person that I have met. They just have these moments where you see like, oh, this kid never got to play. So, now my mom is in her 50s, and she’s playing with the carrot peel to just create something out of it. That was just natural for me. I never even thought about it until my husband pointed out, “Your parents are super-playful. You do pranks. You do fart jokes.” Everything that’s super-immature, we do. I just assumed everyone was like that. But I guess when you’re not carrying the trauma of never having had the chance to really play, you actually get to play for your entire life because it just comes out. It’s a human need to do that. I think that is the magic of life, when all of our adult selves can come out in their true forms and our childhood selves.

Sarah Neilson is a freelance writer. They can be found on Twitter @sarahmariewrote.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY