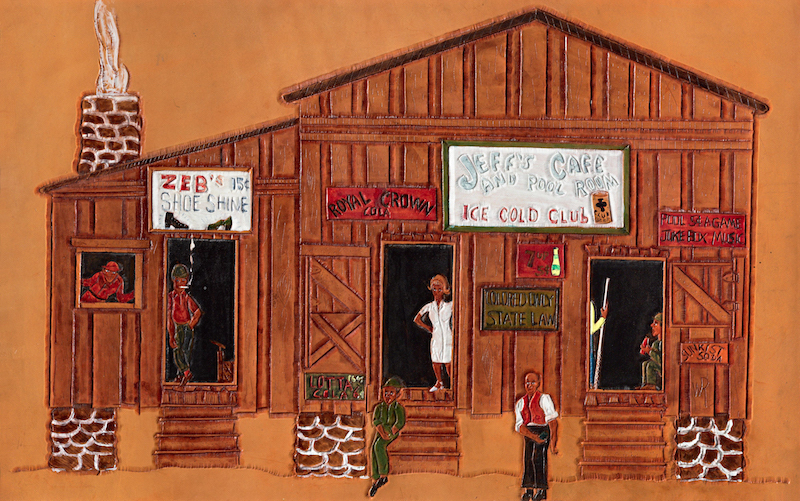

Illustrated by Winfred Rembert. All artworks made with dye on carved and tooled leather.

It was 1961 or 1962. I was working in Jeff’s poolroom. One day I was surprised to see all these Black folk, especially adult Black men, coming in the poolroom. They were all sitting around, having a meeting and talking about civil rights. I never heard people talking about civil rights before. They were NAACP people, though I didn’t know it at the time. I thought they were coming in there to shoot pool, but, lo and behold, they were talking about civil rights. It turned out, if I got it right, that Buddy Perkins, the funeral home director, was the headman of the NAACP in Cuthbert. Jeff was some kind of official too, and Jeff’s poolroom became the meeting place for talking about ideas, businesses, and civil rights.

Jeff’s Cafe, 1997

Jeff’s Cafe, 1997

Black people in Cuthbert had to sacrifice to make a change. In the 1950s, Ben Shorter Sr. was president of a voters’ league in Randolph County. The authorities in Randolph County would not let Black people vote. I remember Mama talking about wanting to vote, and it was obvious that she was afraid. Ben Shorter and some other folks from Cuthbert—Ulysses Davis and Charlie Will Thornton—worked with an NAACP lawyer named Dan Duke to get Blacks onto the voting rolls. As Ben Sr.’s son Wesley tells it, “During the time my father was meeting with a lawyer from Atlanta, they would meet at our house. The lights would be turned out and they would meet in the back room. There were people outside for protection because of threats by the Ku Klux Klan and others.”

The voters’ league was successful in court, but after that Ben Shorter lost his job as a mechanic. Charlie Will Thornton lost her job as a schoolteacher. Ben was also the leader of a swing band that had been very popular in our part of the South since the early 30s.

Wesley’s brother, Ben Shorter Jr., told me that when his father played in some White places, they couldn’t come through the front. He talked about how they all had to come through the back to set up, and how he sat there in this chair waiting on his dad to get through playing. After the voting rights case, it was several years before Ben Sr. was able to get gigs in Cuthbert again.

Ulysses Davis’s granddaughter, Naomi Jenkins, lives in Cuthbert today. She remembers sitting on her grandfather’s knee in the Albany law offices of C.B. King. “Somebody could threaten your life or threaten your livelihood. It just so happened that my grandfather was a carpenter, so he was able to maintain. You shouldn’t have to die for things to be equal and fair, but people died. You should not have had to lose your source of income, but people did. It was very very difficult. The fear was greater than you could ever imagine. Charlie Will. She is my hero. She was very outspoken. She was never able to teach again in Randolph County, simply because of her stand on equal rights.”

*

I had never been to a demonstration or a sit-in. It was all new to me. The NAACP guys talked about how, if you go to the marches, you’d get in the fetal position to keep from getting kicked in the stomach and to keep the dogs from biting you. They taught us to cover our heads if the police were beating on you with those billy clubs, and to fall on the children to protect them. Those were the conversations. My buddies Charlie Brookins and Eddie C. Howard came by the meetings too. Their parents didn’t want them to get involved, so they had to slip out of the house. Charlie says there was no way his parents would have allowed him to go to the demonstrations that were going on in Albany. “It was real dangerous back in those times. White people had guns and they were killing Black people in those marches, far more than you would ever think about or that you saw or heard in the news. It was unbelievable. Stuff you read about in a book is on the good side. My mama would have killed me if I had left and went over to Albany.”

Later on, at the meetings, people talked about Americus. Americus was a tough one. They had this terrible sheriff named Fred Chappell. He was a mean monster. He was above the law. He was the law. He was worse than Bull Connor, the commissioner of public safety in Birmingham who attacked the Freedom Riders. This guy wouldn’t bend. This sheriff was kicking Black folks’ butts every chance he got, hitting them upside the head with his nightstick and giving orders to turn the fire hose on. Back then they would deputize just anybody that was White and give them a badge, and I’d be willing to bet that some of those people wearing the badge and turning on the hose were Ku Klux Klan.

I heard about the demonstrations in Americus in the early days of the Americus movement, and sometimes I would ride over there in a car with guys from Cuthbert and we would sit around in a place on Cotton Avenue called the Bryant Pool Hall. We would play pool and listen to people talk about strategy and what was happening. In 1962, SNCC (the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) started a voter registration drive. Americus had a population of 13,000. Over half of the people were Black, but there were only 300 Black people on the voting rolls. Sam Mahone was a high school student at the time. I didn’t know him back then. I met him in Albany in 2010. He talks about how he escorted people to the courthouse to register.

One day, when he was 17 years old, he took ten people down to the courthouse. Sam was standing across the hallway from the registrar’s office, waiting until each person had a chance to register, when Sheriff Chappell attacked him from behind. “I didn’t hear him coming or anything. He knocked me down, literally, with a fist to the back of my neck. I immediately curled into a fetal position, as we were trained to do, to protect our most vulnerable parts, like our head and our midsection, and he commenced kicking me.”

People who witnessed what the sheriff did would go back and tell others what had happened. Some people who were standing in line even left the courthouse without registering. As Sam tells it, “There was intimidation from the moment you walked into the courthouse, not just from the sheriff but all the Whites who held office there. They were just menacing people who came in there. They did not want Black people to vote.”

People got arrested for trying to buy tickets at the “White” window of the movie theater. The demonstrations got bigger after that. The police brought in dogs and burned demonstrators with electric cattle prods. After the civil rights bill passed, in 1964, there were confrontations over segregated restaurants and a swimming pool. Some SNCC workers, including Sam Mahone, were beaten with tire irons and baseball bats by a White mob after they were refused service at the Hasty House restaurant.

Back then they would deputize just anybody that was White and give them a badge.

Now you had a lot of people in Cuthbert who were afraid to demonstrate. They didn’t want to jeopardize their families or businesses. They didn’t want to take a chance on losing any of that. They would come to the meetings, but they wouldn’t go to the marches. And you had this other group that would put their life on the line. It turned out that was the group I fell into. I was a young boy, 19 years old, in 1965. There were 15 to 20 of us ready to go. We got into a big gray bus that looked like it used to be a school bus and we rode to Americus, which was about 45 miles away. We gathered at the Bryant Pool Hall there on Cotton Avenue. Cotton Avenue was a Black street, with all Black businesses—Black clothing stores, Black poolrooms, Black restaurants, Black funeral home. It’s the main drag for Black folks who hang out in Americus. It was familiar to me because I frequented the place when I thought I was a good pool player.

People were gathering around there from Americus and every which way, too many people to fit into the poolroom, so some were standing around on Cotton Avenue. The leaders say where we’re going to march, and they told us what our strategy was. The strategy was to obey orders—when the authorities say move on, then we move on. We marched from Cotton Avenue down to the main street in Americus. Cotton Avenue ends right at the main street downtown. That’s where we went. It was a peaceful demonstration. People carried signs. The police were there, and the fire department, but they didn’t intervene. People sang freedom songs like “We Shall Overcome.”

Even though it was peaceful, the demonstration was scary. Angry-faced White folks were standing around with their weapons. It was like they were just waiting to jump us. They had guns and axe handles, and we had nothing to fight back with, not even a stick. I had never participated in anything like that, and I wasn’t really demonstrating like I was supposed to. I wasn’t up front, ready to take a beating. I was holding back, somewhere in the middle of the crowd. I was more watching than anything. I didn’t want to take a chance on getting bit by a dog or hit with a billy club. But while I was there, and afterward, I thought about it and decided that if I was going to go, I might as well get out front. So, the next time I went, I didn’t hold back. I jumped off the bus and started yelling, “Come on, y’all. Let’s do this!”

A big crowd was gathering. People came in together, from every which way. This time, the strategy was that when they ask us to move on, we won’t, because we want to get our point across. We want to integrate. We started marching down the street, singing and demonstrating. It was a slow march, just nice and slow, so we know we’re going to get into a confrontation. I’m talking about when they come and ask you to move on, and you don’t move on. You might slightly move on, but you don’t move to the pace that they want you to move.

The first thing they bring out is their dogs, holding them back some, but they are threatening you. I really didn’t want to get bit by those dogs. Then here come the fire department with the hoses. A lot of people get hurt when they turn the fire hoses on you, and I’m pretty sure people got hurt that day, but all that was a little farther down the street. I was up at the other end where the dogs were.

The Attack, 2018

The Attack, 2018

What happened next is that some civilian White folk showed up with shotguns. No uniforms. Some used their guns as billy clubs and were hitting people. Then a gunshot went off and everybody started running and scattering. It was mayhem. I started running too. I knew a little bit about Americus, so I knew where to run. I didn’t wait for anybody to run with. I ran down an alley that was just big enough to drive a car down. It was a small alley off Cotton Avenue, just north of West Forsyth Street, right in the center of Americus. There were a few cars parked here and there. I ran down that alley, and when I stopped to catch a breath, I looked back and saw these two White men coming with shotguns. They didn’t have those shotguns just to shoot squirrels, I’m telling you. They weren’t playing. It happened there was a car sitting there, and I saw the keys sitting in it. Folks left the keys in the car back in the day. I jumped in and took off.

I took that car and drove it to Cuthbert. While I’m driving, I’m thinking to myself, What am I going to do? I didn’t know whether to ditch the car in Cuthbert or to keep driving it, or where to go or who to tell. I was worried about staying alive. That’s what I was thinking about most. I took those folks’ car and I thought I was going to get killed when the police caught me. One thing you just don’t do in Georgia is steal. You can kill somebody and you won’t get as much time in jail as you would if you took something from White folks. White folks in Georgia don’t like for you to take things from them.

You know how you might think one thing and you do another? I was thinking about getting rid of the car, but then the more I rode around in it, I’m saying to myself, Let me keep it for a while. I asked Duck whether he’d like to take a ride in the car. I was riding around in it just for the hell of it. It was something to do. The next thing I knew, the police were riding behind me. If I got it right, my friend Jimmy Greene was in the car with me. I said, “Jimmy, you want to get out? Because I’m going to keep going. I’m taking them for a chase.” Even though I knew I was going to jail, I didn’t want to give up. I wanted the police to have to earn their money. After all the abuse I’d seen them put Black folks through my whole life, I didn’t want to make it easy for them. That’s another reason why I think they hated me so. I gave them problems. They’re used to telling a Black man to stop or come back, and he’ll do that. They actually thought I would stop. I didn’t.

The Getaway, 2015

The Getaway, 2015

Jimmy got out, and I gave the police a chase until I ran the car in a ditch. Then I ran like hell. I was running and running and running until I got tired and climbed up a tree. A little while later, here they come with the most sorry-ass country hound I’d ever seen. I was up the tree and the dog was sniffing around underneath it. Nobody saw me and they left.

They probably went back there and talked to Jimmy. He might have told them it was me driving the car. People will talk when they think they’re going to get in trouble. Some time after that, I was sleeping in an old raggedy car in Cuthbert. The police came and shined a flashlight through the window. They said, “Oooooh Shiiiiit. Look what we got! We got Winfred.” They were really happy to get me.

The police roughed me up and locked me in the calaboose. A couple days later, the sheriff showed up and took me to the county jail. The cook in the jail, Minnie Cooper, told me that Buddy Perkins had been up there looking for me, like he had done before. But they wouldn’t let me out. I never saw Perkins’s face that day. I was in too deep. I don’t know whether they told Perkins I was there or not. But there was nothing he could do; they weren’t going to let him have me.

Weeks went by and I sat in jail. Poonk’s sister, Yolanda Carter, yelled up to the window of my cell from the street. She wanted to know whether I was going to get out. She had to scream to talk to me. That girl got a lot of nerve. The police tried to run her away and she come right back.

I thought about my family, about Mama and all the things she tried to teach me about surviving in a White world, and I knew that old lady was worried about me. I was a young Black man with no structure in his life headed down a path with no good end. I could see that. I remembered men in prison stripes working by the side of the road in Cuthbert. I expected to end up there too, I just didn’t know how long it would be before they sent me to prison.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Chasing Me to My Grave: An Artist’s Memoir of the Jim Crow South. Used with the permission of the publisher, Bloomsbury Publishing. Text copyright © 2021 by Winfred Rembert and Erin I. Kelly. Artwork copyright © 2021 by Winfred Rembert/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.