‘Translators are like ninjas. If you notice them, they’re no good.” This quote, attributed to Israeli author Etgar Keret, proliferates in memes, and who doesn’t love a pithy quote involving ninjas? Yet this idea – that a literary translator might make, at any moment, a surprise attack, and that at every moment we are deceiving the reader as part of an elaborate mercenary plot – is among the most toxic in world literature.

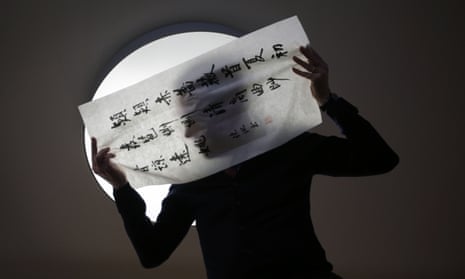

The reality of the international circulation of texts is that in their new contexts, it is up to their translators to choose every word they will contain. When you read Nobel laureate Olga Tokarczuk’s Flights in English, the words are all mine. Translators aren’t like ninjas, but words are human, which means that they’re unique and have no direct equivalents. You can see this in English: “cool” is not identical to “chilly”, although it’s similar. “Frosty” has other connotations, other usages; so does “frigid”. Selecting one of these options on its own doesn’t make sense; it must be weighed in the balance of the sentence, the paragraph, the whole, and it is the translator who is responsible, from start to finish, for building a flourishing lexical community that is both self-contained and in profound relation with its model.

Since I began an MFA in literary translation at the University of Iowa exactly 20 years ago, there have been numerous positive changes in the way translators are paid and perceived. Take the International Booker prize, which since 2016 has split the generous sum of £50,000 between author and translator, thereby genuinely recognising the work as a fundamentally collaborative entity that, like a child, needs two progenitors in order to exist.

Despite this type of extraordinary progress, there is ample room for improvement still. Often enough, translators receive no royalties – I don’t in the US for Flights – and a surprising number of publishers do not credit translators on the covers of their books. This is where the author’s name always goes; this is where you’ll find the title, too. People tend to be surprised when I mention this, but take another look at the International Booker, and you’ll see what I mean.

Since the 2016 launch of the redesigned prize, not one of the six winning works of fiction has displayed the translator’s name on the front. Granta didn’t name Deborah Smith there; Jonathan Cape didn’t name Jessica Cohen; Fitzcarraldo didn’t name me; Sandstone Press didn’t name Marilyn Booth; Faber & Faber didn’t name Michele Hutchison. At Night All Blood is Black by David Diop, 2021’s winner from Pushkin Press, doesn’t name Anna Moschovakis on its cover, although its cover does display quotes from three named sources. Four names, in other words, on the cover of a book Moschovakis wrote every word of. But her name would have been too much.

The underlying assumption on the part of many publishers seems to be that readers don’t trust translators and won’t buy a book if they realise it’s a translation. Yet is it not precisely this type of ruse that breeds distrust, and not translation itself? What tends to encourage a reader to pick up an unfamiliar book is the thrilling feeling that they are about to embark upon an interesting journey with a qualified guide. In the case of translations, they get two guides for the price of one, an astonishing – an “astounding”, a “wonderful”, a “fantastic”, a “fabulous” – bargain.

We desperately need more transparency at every level of literary production; this is just one example, although I do feel it’s an urgent one. Translators aren’t like ninjas. But we are the ones who control the way a story is told; we’re the people who create and maintain the transplanted book’s style. Generally speaking we are also the most reliable advocates for our books, and we take better care of them than anybody else. Covers simply can’t continue to conceal who we are. It’s bad business, it doesn’t hold us accountable for our choices, and in its wilful obfuscation it is a practice that is disrespectful not only to us, but to readers as well.