Many years ago, when I was twenty-one, I met this woman named Cleo. Her style was a careful, curated mix, a curation I now can only describe as a trans dyke who takes pains to pass, but she’s still a dyke. She wore a long black hoodie with red trim and patches sewn on with dental floss. Bright red lipstick and a nose ring big enough to hurt somebody. She had black hair and green eyes.

This was during a time when I didn’t know anyone like myself. We were on a bus going downtown. She had a water bottle in one hand and was whispering into her phone in the other. I was a row behind, where I could watch her. She got off in Old Town, and I got off, too, and followed after her and said, “Hey!”

Her shoulders tensed before she turned. She softened when she saw me.

“Sorry,” I said. “Hi.”

“Hi? Do I know you?”

“Maybe. Sorry, this is weird. Are we sisters?”

The internet taught me that move.

She finally smiled then. “I think we are.” She shook my hand, and it sent a cool bolt through my arm. “My name’s Cleo.”

“I’m Nicole.” We stared at each other awkwardly. It’s age-old. You meet someone whose mould of pariah weirdo looks something like yours, and you try to reach out, but you’re on guard, because what if you hate each other, or what if she sucks—plus, what if somebody clocks the two of you together when on your own you would’ve gone undetected? That mode of thought was around more back then, partly because of gatekeeping bullshit and partly because of good reason.

Cleo said, “Do you want a drink?”

I sipped from her water bottle (vodka) and handed it back and she tipped it up. And her body visibly relaxed. Like I could see the electricity running through her veins.

Next thing I remember, we were walking over the Burnside Bridge. She asked, “How old are you?”

“Why do you care?”

“Because you’re cute, that’s why.”

It was there, right there, that I knew I loved the sound of trans women’s voices. I remember the exact cadence of how she said it. The memory of this sentence would have me clocking would-be stealthers for years, no bullshit. The slight elongation at the end, the pitch-dip in the middle of the sentence. Not that we all talk the way she did. But some of us do.

“Are you saying you want me older or younger?” She laughed. “Okay, that’s creepy. Let’s talk about something else.”

“I’m twenty-one exactly. How old are you?” “Oh shit,” she said. “Girl, older than you.”

She led me to an old warehouse in the Central Eastside with offiCe liQuiDAtors painted on the front in three-foot letters. Cleo moved through an open door. “Follow me.”

We walked through lit hallways. We heard the voices of people at work, faint and far away. Cleo turned up a flight of stairs, and suddenly, we were in a cavernous, slanted room. It was like an enormous lecture hall, but filled with desks and rolling chairs and filing cabinets instead of seats.

“Check it out!” She scrambled up toward the back. Her hoodie was falling off her shoulders, and the light made a huge shadow of her on the wall. We were at the top and panting. “Turn around,” she said.

There was a huge window on the other side of the room taking up the upper half of the wall, looking onto the interstate. It was near sunset, and the concrete was blasted with light. You couldn’t see the skyline on the river’s other side.

“This is pretty,” I said, awed.

“You’re pretty,” she said. She said it with sass. She said it without looking at me. Then she said, “Do you want to make out?” That was another first for me: the idea that you’d ask. We kissed slow, delicately, and I felt for the first time the largeness of another human’s body as beautiful.

Later, in the dark, we walked through a cemetery swigging from her water bottle, and there was, of all things, a rolling office chair sitting in the middle of a path. She flopped into it and said, “Push me!” I pushed her down the walk until the chair spun out and she landed in the grass. I got in and she pushed me, hooting all the way out to the street.

We passed a woman in the cleanest, crispest shirt in an empty, bright shop. She was putting racks up on a wall and her front door was open. Cleo asked, “What are you doing?” and the woman in the crisp shirt said, “I’m putting in my store. I’m going to sell clothes!”

Cleo pushed me on ’til we stopped at a light, and I stood up and kicked the chair spinning into a doorway. “I’m drunk!” I said with surprise. A falter of sadness crossed Cleo’s face. “Yeah,” she said. “I have that effect on people.”

She led me through a backyard filled with purple lights to a detached garage. Inside: a concrete floor and no insulation, a dresser and a space heater and a bed with a sleeping bag for a blanket. She turned on the heater and said, “Come here.”

She fucked me with my legs straight up, gathered in one of her arms.

The next morning, she took me in the house to make breakfast. There was detritus on every surface of the kitchen and a bookshelf filled with gay shit and mass-market sci-fi. In the living room was a makeshift bench press, above which was a Sharpie’d sign: I AM A QUEER MUFF-DIVING SPARKLE GLITTER FAGGOT AND PROUD.

I leaned over to kiss her as she whisked eggs. She kissed me back, and then suddenly she had me by the hair and leaned me back over the stove with her hands in my crotch and, God, it was fucking hot, and I cried out, and then I apologized and she gave me a look that was very stern and said, “Loud sex is allowed in this house.”

I had to work after we ate, and noon found me on a bus going into the far north of the city smelling like cum and grease, looking out the window onto what felt like a different earth.

We hung out once more before she split town. She was already drunk and we went to the old nickel arcade. We had a hoot. She dominated at pinball. The next morning, she put on country tunes while we lay in bed. A man and a woman were singing together and it was beautiful. Punks who like country! There’s a lot of them, huh? I have fond memories of that.

Cleo got up and told me to wait. She returned with breakfast in bed, and ugh, how fucking sweet is that, right? But—it freaked me out. I don’t know. I was attracted to her, I liked hanging out and I liked the sex, but I didn’t feel anything more. Which I wasn’t able to say.

You may remember I did not always understand how one responds to romantic intimacy.

I ate her toast and eggs, and then got up and was all “Well, I gotta work!” though my shift didn’t start ’til one.

And as I was getting dressed, with the space heater roaring, Cleo said in a voice that broke out of a sob, “Could you…Could you just come cuddle me for a bit?”

Cleo had radiated power and confidence until that point, power and confidence I had given to her without knowing. (Here’s a secret: I used to fret my name was boring, but know why I like it now? No one overestimates a Nicole.) I took my clothes back off and got into bed and I felt her body unclench while mine left the room.

She said, “We’re meant to be kept from each other, you know,” her verve returned.

She bounced out of town a few weeks later. She was one of those punks who did that, drifted. How she stitched her life together, I don’t know. But before I left that day, Cleo burned me that country album. I found out later it was Robert Plant and Alison Krauss doing covers, and I thought of Cleo every time I listened to it, though I wouldn’t see her again for a dozen years.

You know the rest of what happened to me, or some of it, anyway. I fell in love with a boy, a young boy from Lake Oswego whose innocence and sweetness befitted his eighteen years. He’d just left his family and the Mormon Church, and we bonded for a long time over that. He more or less moved into my room while we were together. He was a magical boy. Good at fixing things. Twice, he bought me groceries while I was literally napping, exhausted from work. He was a nice boy. We had both been made for different lives, except I couldn’t go back, and he could, and eventually, that’s what he did.

I moved in with Lloyd after that. I had no idea what else to do. He posted that he was looking for a roommate, and I responded, and suddenly, I was living with him.

I called him, by the way, with the news about you. He always thought of you fondly, always, I want you to know.

One night, I went out for dinner with Lloyd and his girlfriend at Marie Callender’s. I told them I’d been talking to this Canadian guy on the internet.

Lloyd said, “Wasn’t your grandfather born in Canada or something? Can’t you apply for citizenship with that?”

I said, “Yeah, New Brunswick, but I dunno.”

Lloyd lost it. “How many people like you!”—he paused—“I mean, in your situation, would give an arm to just up and go to Canada?” Provinces had just begun to fund bottom surgery again, and Lloyd knew I wanted it. (Lloyd asked me about bottom surgery a lot.)

I didn’t have a good answer. His girlfriend put a hand on his arm. “Sweetie, this is her home. Maybe it’s not that simple.”

That night, after jerking off before bed, I started crying. (Very tragic tranny.) I slumped against myself and I thought, He’s right. There’s no shame in taking an exit that’s good. When else will it happen?

I might really believe that. Every now and then you get offered an exit, something you didn’t plan for, something you don’t deserve, and something you don’t believe you can rely on. So you don’t take it. Eventually, I realized: It doesn’t matter. No one deserves anything, really. I was on a plane a year later.

I stayed in Edmonton with that boy from the internet for a long time. He worked camera at a news station, he was obsessed with urban planning; he had a thing for getting tied up and he thought that was extreme and I loved that about him. And his parents—ugh—they were beautiful souls, apostates from a little Mennonite town. They made room for me in their family without question, and they were so incredibly kind. Those were a good few years. I built a life in that city, and yes, I got my pussy. I could’ve stayed with that boy forever, but one winter evening, as wind rage-whistled outside, he looked at me in the yellow kitchen light and he said, “I’ve been seeing someone.”

I looked for a job to get me out of town, anywhere away from him. The publishing company here had a paid internship, and I jumped on it, and then they kept me. I’ve been here a while. Cleo came back into my life last fall.

Cleo was part of this network I’ve only ever glimpsed through the internet, a network of trans women travelling and loving and fucking each other. She lived in LA, working as a midwife, but still, one day I’d see pictures of her picnicking in Chicago with other girls in sundresses, and then suddenly I would see pictures of her in Tennessee, the girls wearing leather shorts and glitter and holding chainsaws.

This isn’t to say I wanted what I assumed these women had. I knew the life I wanted and the life I didn’t. I mean to say it fascinated me, and that when Cleo messaged me last November, to say that she was here, she was stuck, and could she crash with me?—sure, it was a surprise, but it also made perfect sense. Like of course, after all this time, this was the context in which I’d see her again.

I’d been walking home by the river when she messaged. The air was brisk and cool. There was bullshit with my passport, Cleo explained. They just let me through but my bus left hours ago.

I told her I was close to the tunnel; I’d be on my way. She said, What’s your compatibility with bars?

__________________________________

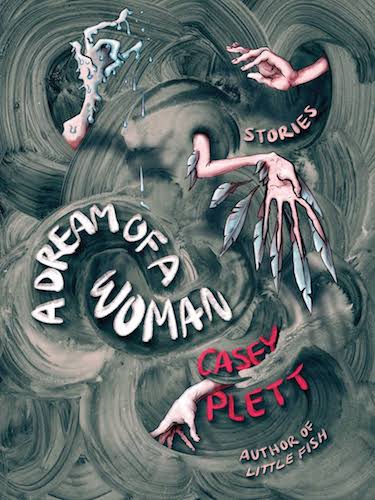

From the short story collection A Dream of a Woman by Casey Plett (published by Arsenal Pulp Press, 2021). Excerpted with permission from the publisher.