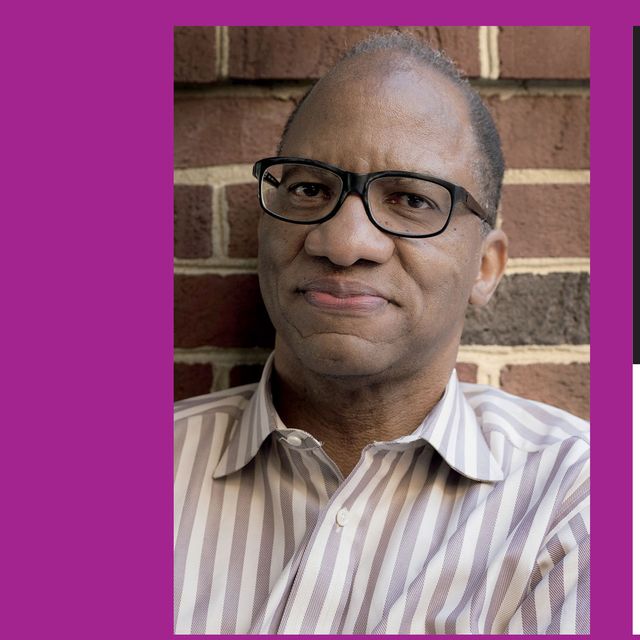

Author Wil Haygood is no stranger to cinema. He not only has a lifelong love of film, but the author and Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Humanities fellow also got a firsthand look at the movie-making process when his 2008 Washington Post article “A Butler Well Served by This Election” (and the subsequent book The Butler: A Witness to History) inspired the 2013 film Lee Daniels’ The Butler, which featured an all-star cast including Oprah Winfrey, Terrence Howard, Vanessa Redgrave, John Cusack, Jane Fonda, David Oyelowo, Robin Williams, and so many others.

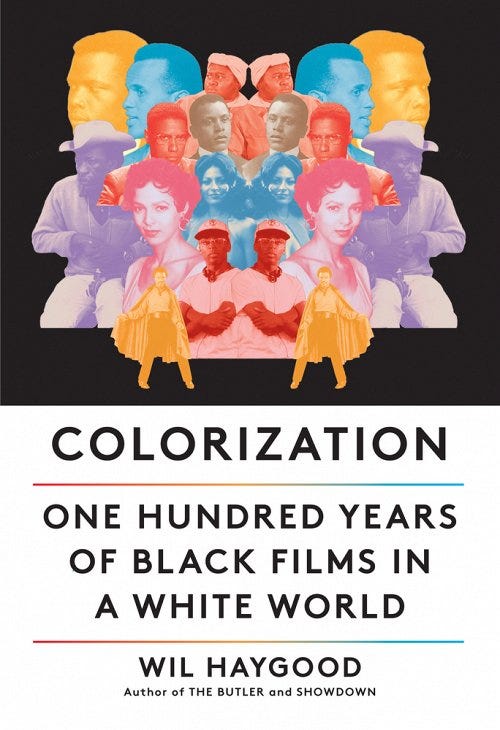

It was on that very film set that the seed was planted for Haygood’s new book, Colorization: One Hundred Years of Black Films in a White World. Starting in 1915 with D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation and spanning all the way to present-day Hollywood with sections on Black Panther and Jordan Peele, the book is an exhaustive look at the way cinema, race, and history have all changed, commingled, and adapted over the past 100 years. At once a film book, a history book, and a civil rights book, Haygood’s tome is a stunning achievement in every possible way: extensively researched, intricately detailed, beautifully written, and massively entertaining. Colorization is, without a doubt, not only the very best film book of 2021, but it is also one of the best books of the year in any genre. An absolutely essential read.

Shondaland recently spoke with the author via Zoom to discuss the book, Black cinema, the changing face of history, and the amazing piece of advice he received from the master himself, James Baldwin, more than three decades ago.

SCOTT NEUMYER: I really do love this book. I think it’s extremely well written and super-comprehensive about a subject that for far too long hasn’t been given enough attention. Can you give me a little bit of insight as to why you decided to write this book and why now was the time to do it, aside from the obvious 100 years tie-in?

WIL HAYGOOD: When I was a kid growing up in the ’60s, my mother would allow me to go to the movie theater every Sunday. I would walk like seven blocks, and they were really my first solo trips outside of the house as a kid. I would go straight to the Garden Theater movie theater and sit in the dark. They had velvet curtains that would open, and it just seemed like a very magical time to be someplace. I would look up at the screen, and I fell in love with all of these actors. It was Charles Bronson, Lee Marvin, Robert Mitchum, and Elvis Presley. There was Connie Stevens and Richard Burton and Paul Newman — just a wide array of actors and actresses. And they all had one thing in common: They were all white. At this neighborhood movie theater, they were all white. And as the years went on — I went to college in the ’70s — I would come home, and there was a new theater, the Southern Theatre downtown. And it was the first theater in my hometown of Columbus, Ohio, that was showing Black movies. Superfly. Foxy Brown. A lot of Pam Grier movies and Richard Roundtree movies.

I think, as the years went on, I started to realize that there are two Americas, in a sense: Black America and white America. And with that, there were also two mindsets when it came to filmmaking. It really fascinated me. As I started to become a journalist and then a foreign correspondent traveling around the world, I would land in these foreign cities, and the first thing people I met would want to talk about was cinema and movies from America. Movies really do bind us all. We all have something in common in this world, and it’s film.

I was on the set of The Butler in New Orleans, and I was around much of the talent one evening — we were having a kind of a soiree — and I was looking at this talent, Black and white actors. There was Oprah Winfrey. There was Terrence Howard. There was Vanessa Redgrave and Jane Fonda. It was just a really, really wonderful cross section of talent who had gathered to make this movie about this White House butler who worked for a president. And I was just standing there and said, “Wow, somebody should write about this moment and this history of cinema, and how when it works for the good, it is really astounding.” So, Terrence Howard was near me, and he walked over to me, and he said, “Well, you’re the writer. So, you write that book.” And I think that the seed was set.

I think too for me to write about film is one thing, but then to write about what’s going on in the street at the same time is something we rarely see done in books. I think that really drew me to it as well. To be able to tell the story of the growth of cinema right alongside the growth (or setbacks) in this country.

SN: It casts such a wide net, but it’s also so detailed that it doesn’t feel like there’s anything missing. This feels like a cinema book and a history book and a civil rights book. And it’s beautiful in all those ways. It’s also quite current, so I assume you were still writing and researching up through the pandemic. Did that time over the past year and a half provide any additional insight into the subject, especially in terms of Black agency, ownership, and the difficulties faced by underserved communities?

WH: That is a super question because I started the book in 1915 with D.W. Griffith’s incendiary movie The Birth of a Nation. So, I’m sitting here in my home, and there is the Charlottesville Nazi march with KKK flags, and I’m almost getting tears in my eyes because I’m sad, thinking, oh, my God, it is happening again. The same thing as in 1915. Here we are in America, Charlottesville, not far from where I live in Washington, D.C. That happened. And then a few years later, you have the George Floyd murder in public. The whole world woke up to the question of “What does it mean to be Black?” And then you had the film community into that conversation as never before.

During the March on Washington in 1963, a lot of actors wanted to go who were white, and they were told by their agents, “Don’t do it. It might harm your career.” So, there were just not very many white actors there — you can name them on your hand. There was Paul Newman and Tony Franciosa and Marlon Brando. It was a very small contingent of white actors. A whole lot of Black talent came there. And so it really was wonderful to see Hollywood raise its head [recently]. Actors and actresses, movie directors who are Black raise their heads, because they’ve been saying this sort of quietly for years, but now I think they have more boldness to say it outright.

SN: What are some of the films that you wish you could have included in the book but didn’t for some reason, either due to space or they just didn’t fit?

WH: One of them is Sparkle, the 1976 film. Another is a kind of unknown film with [Philip] Michael Thomas called Book of Numbers (1973). I wish that I could have written more about some of the Black Westerns that were made in the 1930s. Maybe a little more about the silent-film era, but I do give a whole chapter to that amazing, amazing Black filmmaker, Mr. Oscar Micheaux. Just what he did is so phenomenal. I mean, he goes to South Dakota, has a farm, raises animals and crops. Then he writes books and tells himself that he has the talent to adapt his own books. So, he raises money and travels around the country to talk to theater owners and charms them to show his films. Where is the Oscar Micheaux movie, you know?

SN: That’s a great question. I’d love to see one made. If someone saw your book, picked it up, and now wanted to start diving into Black cinema in a really meaningful way, what are the four films you would tell them to watch first?

WH: One would definitely be Porgy and Bess (1959). Great film. Great cast. Another one would be another Sidney Poitier film, In the Heat of the Night (1967). I’m trying to go decade by decade. Spike Lee’s Malcolm X (1992). Phenomenal. And another one would be Lee Daniels’ The Butler (2013). Those are the four I would say they should start with.

SN: What are some of your go-to books that touch on these subjects?

WH: One is The New Biographical Dictionary of Film by David Thomson. Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood by Mark Harris. And the third is not really a film book, per se, but it’s a book by James Baldwin called The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction: 1948-1985. Baldwin wrote a lot about film. He loved the movies, and he was heartbroken with Hollywood. And so there are quite a bit of his film reviews in this book.

SN: Those are great choices. What are you proudest of in your life and career?

WH: I think what has mattered to me is hearing folks say, “I hadn’t read a major Sammy Davis Jr. biography until yours,” or “I hadn’t read a major Sugar Ray Robinson biography until yours.” And folks are now starting to say to me, “This book that you’ve just written on film is not like any other book on film that I have read.” And I think that is what makes me feel good. It’s that I have found a side door, an added door, to dive into the home where I could ferret out or haul out the stories, and that people find that they seem like new stories, and these characters have been around. We know about Sammy Davis Jr. and Harry Belafonte, but I think to tell them in a new way, like I have tried to do in this book, that matters to me, and it makes me feel that my hard work has been worth it.

SN: What’s the best advice you’ve ever received?

WH: I hate to name-drop here, Scott, but it was before I had ever written a book, and I was at The Boston Globe. They sent me up to the University of Massachusetts at Amherst to interview a writer who was a visiting writer there that year. And the writer happened to have been James Baldwin. And I had not written a single book at that point. This would have been 1984. [Editor’s note: The story actually ran on October 27, 1985, in The Boston Globe.]

And I had said to myself that, at the end of my session with him, I was going to ask him if someday I would be able to write books. And I did. I said, “Sir, can I ask you something personal?” and he said, “Oh, sure, baby. Yeah, go ahead.” And I said, “I wonder, Mr. Baldwin, if I, someday, will be able to write books.” And he looked at me, and he said, “How in the hell should I know that?! I have no idea, my man, if you’ll ever be able to write books!” [laughs].

Scott, my head dropped out of shame. I wanted to run out of that house where he was staying. I was just ashamed that I had asked something that he thought was so silly, but then he leaned into me, and he said, “But I will tell you this: Whatever you do in life, you must go the way your blood beats.”

I have that quote on my wall in my writing room.

SN: That’s amazing.

WH: He was nose to nose with me, and he said, “Whatever you do in life, you must go the way your blood beats.” And I just took that and wrote it down. And I have had that note with me all these years later, all these nine books later, because that’s what I wanted to do. Even when I became a newspaperman, I always had ideas to write books. And he told me to go the way my blood beats, and that’s what I’ve been doing.

Scott Neumyer is a writer from central New Jersey whose work has been published byThe New York Times, The Washington Post, Rolling Stone, The Wall Street Journal, ESPN, GQ, Esquire, Parade magazine, and many other publications. You can follow him on Twitter @scottneumyer.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY