There is a small monument to Sylvia Marie Likens in Willard Park in Indianapolis, Indiana, not far from a house that once stood at 3850 East New York Street, where they beat the girl with a police belt, a fraternity-style paddle, and a curtain rod, where they lowered her into scalding baths, pushed her down stairs, rubbed salt in her wounds, forced her to drink urine and eat excrement from a baby’s diaper, where they dehydrated and starved her and put out cigarettes on her body, where they branded words into her abdomen with a burning poker, and where they finally killed her.

Movies have been made about her. True crime stories about her have appeared regularly over the years. Several novels have been based on her story. One of the defense lawyers, Forrest Bowman Jr., wrote about the trial many years later and published a book in 2014. Kate Millett, artist and scholar, author of Sexual Politics, built cage sculptures about Sylvia and wrote The Basement: The Story of a Human Sacrifice, in which she tries to make sense of it all. Part true story, part cultural-philosophical-feminist critique, part novel, Millett’s book includes the running thoughts of victim and perpetrators, an effort to capture what the author imagines happened from the inside, but for me there is something wrong with this ventriloquism, and the imaginative intrusions fail. In House of Evil: The Indiana Torture Slaying, the journalist John Dean doesn’t try to make sense of it all. He tells a story, and he reports: “Child after child, when asked to explain why he or she participated, said simply, ‘Gertie told me to.’”

The Indianapolis Star, October 27, 1965:

A mother of seven children and a 15-year-old boy were arrested on preliminary charges of murder last night after they were implicated in the death of a sixteen-year-old girl who had been tortured and murdered. Investigators said a sister of the victim told them at least three of the woman’s children took part in some of the beatings while the victim, Sylvia Marie Likens, was bound and gagged.

Arrested were Mrs. Gertrude Wright, 37, and Richard Hobbs, 15, 310 North Denny Street. Another teenage boy was being sought. [Later reports would identify the woman as Gertrude Baniszewski.]

Detectives said Hobbs admitted to beating the girl “10 or 20 times” and carving the words “I am a prostitute” on her stomach with a needle.

The Indianapolis Star, October 28, 1965:

The 16-year-old girl was systematically beaten and tortured over a three-week period by at least 10 persons, probably more, police said.

The Indianapolis Star, April 30, 1966:

A weeping Jenny Likens was led from Criminal Court Division 2 yesterday as huge photographs of the fantastically mutilated nude body of her sister were shown.

From the Trial Transcript Testimony of Jenny Fay Likens:

Q. Did Sylvia eat at the table with you when you had meals?

A. Not all the time.

Q. When you first went there, did she?

A. Yes.

Q. In what way?

A. I don’t know they kept saying she was not clean and they did not want her to eat at the table.

. . . .

Q. What did you see and what was said?

A. She [Gertrude] said, “Come on, Sylvia, try to fight me.”

Q. When did this happen, Jenny?

A. In September.

Q. When did—where did it happen?

A. In the dining room.

Q. What did you see and what was said?

A. Well Gertrude just doubled up her fist and kept hitting her and Sylvia would not fight back.

Sylvia Likens was not Anne Frank, a girl who hid with her threatened family in an attic, wrote brilliantly about her life, and died in a Nazi death camp, Bergen-Belsen, because she was a Jew and had been designated unfit to live by the authorities of the Reich. She was not Mary Turner, who bravely spoke out against the lynching of her husband, Hayes Turner, and was then lynched herself in Lowden County, Georgia, during what is now called the “Lynching Rampage of 1918.” The mob disemboweled Mary Turner and then stomped on the eight-month fetus she was carrying, under the watchful eyes of another mob of several hundred white people who had gathered to watch. Likens’s death did not ignite protests, political writing, and activism as Mary Turner’s death did and still does. Likens was a poor white girl in a poor white neighborhood in Indianapolis. Deprived as she was, she was still a white Protestant in the United States. Her story isn’t easily swept into the narrative of a just cause. It is not obviously political.

The forces aligned against Sylvia Likens were not the fearsome powers of the state and a malign ideology of racial purity. The mother of seven, Gertrude Baniszewski, was not carrying out anyone’s orders.

When academics turn to the Likens case, it’s Millett’s book that interests them, the author’s fascination, obsession, and analysis, not the facts of the actual murder. In “The Basement: Toward a Reintroduction,” Victor Vitanza begins his essay with a warning. He will not “paraphrase” Millett but include direct quotations from the book: “Hence this discussion contains explicit descriptions of sexual violence.” He calls Millett’s style “paraorthodox.” His essay is clearly not intended for the uninitiated. In Murder: A Tale of Modern American Life, Sara L. Knox doesn’t discuss the news coverage of Sylvia Likens’s torture and death, although her subject is the role murder has played in the postwar United States. Instead, she devotes many pages to The Basement. The destroyed body of a particular girl, a body Millett cannot take her eyes off, is a blur in Knox. As I read, I paused to look at the spelling of the criminal’s proper name; a typo perhaps? Throughout her text, Knox misspells the last name of Likens’s torturer as Gertrude Baniewski. The s and the z have gone missing. (Victor Vitanza, Sexual Violence in Western Thought and Writing: Chaste Rape, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. Sara L. Knox, Murder: A Tale of Modern American Life, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1998.)

What’s her name? You know, the monster woman with a Polish last name who murdered that girl in Indiana? Kate Millett wrote about her.

The scholarly third person frequently serves as a hideout from horror. “All in all, intensive research on violence can be straining when one is emotionally involved, and detachment remains important.” This sentence appears in a paper called “Studying Mass Violence: Pitfalls, Problems, and Promises” in the journal Genocide Studies and Prevention by Uğur Ümit Üngör. Exactly how detached should one be? Reiterating the details of the torture and murder of just one person, Sylvia Likens, is more than “straining,” even though a woman and a gang of kids do not qualify as a mass. There is a leering fascination attached to the Sylvia Likens case, a queasy merger of moral outrage and titillation. To write about it is to become a vicarious participant in the girl’s victimization and humiliation. I am doing it now, writing about it, and to what purpose? The story has the tawdry outline of a horror film, and the crimes against Likens, although not all explicitly sexual, reek of shameful urges, veiled excitement, and sadistic sport of an erotic kind. Prurient voyeurism still clings to the case like cheap cologne to a crowd of people in an elevator. And the stink does not go away.

During the trial, it became clear that Sylvia had not been officially or technically “raped.” According to the coroner who examined her body, her labia and vagina were swollen from external assaults, but her hymen was intact.

How the world has worshiped at that absurd threshold: the border between female purity and impurity, between cleanliness and filth.

The surname of the accused woman was subject to considerable confusion. In the early days of news coverage, she was identified as Mrs. Gertrude Wright, but soon became Gertrude Baniszewski. In the trial transcripts, she is sometimes Baniszewski and sometimes Wright, depending on who is talking. At sixteen, the girl who would grow up to become the only adult in the Likens case charged with murder dropped out of school to marry John Baniszewski, an Indiana policeman. After ten years, four children, and assault and battery from Officer B., Mrs. B. divorced him and married a Mr. Gutherie. Gertrude’s metamorphosis into Mrs. G. lasted only four months, and the surname evaporated with the man. She returned to Mr. B. As far as I have been able to tell, the two never remarried, but before their alliance came asunder for a second time, she gave birth to two more children. Gertrude lifted the name Wright from her post-Baniszewski, much younger paramour, Dennis Wright, who beat her badly enough to send her to the hospital twice, fathered her seventh child, and then absconded.

Whatever legal niceties might have been involved in determining the name of the accused woman, the courts and news organizations finally settled on Baniszewski as the name that met the standards of legitimacy.

Six of Gertrude’s children, who ranged in age from eight to seventeen at the time of the murder, were the legal offspring of Baniszewski, who was himself a finger in what has been called “the long arm of the law,” but which in the Likens case turned out to have the reach of an amputee. Gertrude’s baby, who went by the first name of his vanished father, was not officially Dennis anybody, as he had, by no fault of his own, arrived in the world a bastard. It is helpful to recall that in 1965 in that neighborhood in Indianapolis, children born out of wedlock did not sit well with the neighbors. No doubt the eyes of the neighbors spawned the fictional character known as Mrs. Dennis Wright.

The forces aligned against Sylvia Likens were not the fearsome powers of the state and a malign ideology of racial purity. The mother of seven, Gertrude Baniszewski, was not carrying out anyone’s orders.Gertrude was not the only Baniszewski to be charged with homicide. Every one of Officer and Mrs. B.’s children hurt Sylvia Likens but only two of them were tried for murder: Paula and John. Paula, the oldest, pregnant after a misadventure with a married man, assaulted Sylvia with such ferocity on one occasion that Paula broke her hand. While on trial for her life, Paula pushed a new life into the world, a girl she belligerently named Gertrude. John Jr., twelve years old when Sylvia died, and two neighbor boys, Richard Hobbs and Coy Hubbard, were also tried for Sylvia’s murder. The three Baniszewskis, Hobbs, and Hubbard were all convicted, but none of them was executed. Gertrude served the longest sentence, twenty years. She became a model prisoner and was known to her fellow inmates as “Mom.” After the three Baniszewskis were released from prison, they all changed their names, as did Officer Baniszewski, who had not taken part in any of the household torture.

When my mother read about terrible crimes in the newspaper, she used to say, “No sane person could do such a thing.” Gertrude Baniszewski’s defense lawyer, William Erbecker, articulated the same sentiment in court: “She’s not responsible because she’s not all here.” He then tapped the side of his forehead with his index finger to emphasize that the problem lay in that part of the woman’s body. The deputy coroner of Indianapolis, Dr. Arthur Kebel, who had examined Sylvia’s corpse at the house, testified in court that when he had first seen the body, he had guessed the damage was the work of “a madman.” After perusing the photographs of the dead girl in court, he said, “If I had nothing to see except these pictures, I would say only a person completely out of contact with reality would be capable of inflicting this type of agony on another human being.” He said “person,” not “people.”

The lone gunman who “snaps” and begins firing his weapon in a church, synagogue, or school, and the sadistic psychopath who secretly stalks his prey are easier to keep at a comfortable distance by reason of mental illness than any group, small or large in number, that turns on its victim(s) with rabid fury. What about the underage mob that came and went at 3850 East New York Street in Indianapolis under the direction of a thirty-seven-year-old woman?

In La psychologie des foules, 1895, translated a year later as The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind in English, Gustave le Bon proposed a theory of the “group mind,” an unconscious force created by a contagion of feeling that quivers through its multiple individual parts to become a single mental reality. “The crowd is credulous and readily influenced by suggestion.” In the grip of this contagion mentale, a person enters a kind of hypnotic trance. His conscious personality vanishes, and he moves to the rhythms of the greater whole. Crowds, le Bon’s theory goes, are impulsive, irritable, irrational, volatile, and morally righteous. They become, he maintained, like those beings who are insufficiently evolved—“women,” “children,” and “savages.”

Gabriel Tarde, another French scholar of the period, was interested in how thoughts and feelings spread in populations. “What is society?” he wrote. “I have answered. Society is imitation.” Imitation, Tarde believed, usually worked by underlings imitating leaders, not the other way around. It can move beyond an immediate group and be caught by others. Bandits, for example, “an antisocial confraternity,” reinforce one another’s “toughness” within the group, but those mores “radiate” beyond the circle too, working their way into those vulnerable to its seduction. (Gabriel Tarde, The Laws of Imitation and Invention, trans. E. C. Parsons, New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1903.)

On May 19, 1966, the jury found Gertrude Baniszewski guilty of first-degree murder. Not three months later the same year, on the afternoon of August 5, tenth-grade students at the Girls Middle School in Beijing attacked three vice principals and two deans. They threw ink on their superiors, crowned them with dunce caps, forced them to their knees, scalded them with boiling water, and beat them with nail-spiked clubs. After three hours of torture, the first vice principal, Bian Zhongyun, lost consciousness. The girls tossed her into a garbage cart. She died. Bian Zhongyun was the first teacher to be sacrificed to the Cultural Revolution in China. Fourteen days later onstage in a concert hall near Tiananmen Square, students from Beijing’s Fourth, Sixth, and Eighth Middle Schools whipped and kicked twenty teachers in front of a crowd of thousands. One witness said they were beaten so badly “they no longer looked human.” The children had been given permission. They had the state on their side. (Youquin Yang, “Student Attacks on Teachers: The Revolution of 1966,” University of Chicago, Issues and Studies 37, 2001.) Does “Gertie told me to” constitute authoritative permission under the roof of a single-family house?

Gustave le Bon, creature of late-nineteenth-century science and its research into hysteria and hypnosis, believed in “suggestion,” a traveling underground message that infects the crowds that fall under its spell, a form of enchantment explained in the naturalistic terms of the period. Tarde, who was also interested in crowds and crime, posited “imitation rays” that move through society. Imitation can be a form of somnambulism. “To have only received ideas while believing them to be spontaneous: this is the illusion to which both sleepwalkers and social man are prey.” I think it’s my thought and my action, but it’s not. I am under the influence of contagious rays that have almost magical properties to sway my will.

If the ending were changed, the story of Sylvia and Jenny could be told as a fairy tale.

Long ago in the city of I., there lived a poor man and his wife and their five children. Try as they might, the man and woman could not make a living in town, and when only a few coins remained in the family purse, they decided their only choice was to leave the children behind and try to make their fortune with a traveling carnival. Their oldest girl had married and lived with her husband, and their boys had a home with their grandparents, but the two youngest daughters, Sylvia and Jenny, had nowhere to stay. Sylvia was a pretty, obedient girl, who liked music and dancing. She helped her mother keep house and watched over her little sister, Jenny, who wore a brace on her leg and walked with a limp. The man and woman watched their money dwindle and prayed they would find lodging for their girls.

One summer day, Sylvia and Jenny wandered into the street and met a merry, mischievous girl named Stephanie who took them home with her. After the sun had set and his daughters had not returned, the man went out looking for them, discovered their whereabouts, and knocked at the door of a tall, broken-down house. An ugly, haggard woman appeared, and the man took fright, but when she spoke to him, her voice was sweet and mellifluous, and he no longer felt afraid. He asked after his daughters, and the woman told him her name was Gertrude and she had seven children of her own. Soon the two had struck a bargain. For twenty dollars a week, Gertrude agreed to watch over Sylvia and Jenny as if they were her very own. Father and mother bade goodbye to their daughters, went on the road, and promised to return before the autumn leaves fell.

Now, this Gertrude was a powerful witch. When the money she had been promised didn’t arrive, she beat Sylvia and Jenny. When the money came in the post the next day, she beat them anyway. But as time went on, the witch turned all her wrath on Sylvia because she could not bear the sight of her youth and beauty. The witch cast a spell over the house so that everyone inside its rooms felt the same hatred she did for Sylvia, everyone, except Jenny, on whom the magic did not work. But when the children from the neighborhood entered the house, they too fell under the charm. The witch and the hexed children hit Sylvia. They laughed at her. They called her a slut, gave her crumbs to eat, and made her sleep in the basement on the floor. And Jenny with her lame foot was too afraid to say or do anything.

It is at this moment that a white dove flies through a small window and speaks, or a fairy godmother appears suddenly with her wand to grant three wishes, or a strange little man waddles into the room and asks our heroine to guess his name, but while Sylvia lies weeping in the basement of the terrible, enchanted house, no one comes, and she dies.

Most people want stories that make sense. The evil witch is banished or killed. She melts. Virtue rewarded. Justice done. Wishes granted. Moral lesson learned. Plucky hero fights like mad, defies all the odds, and survives. Music soars. Applause is heard. Standard cultural narratives are already there waiting for us. We pick them up, dust them off, and apply them when they come in handy. Beowulf, Cinderella, Odysseus. Stories are spun for meaning. They locate cause and effect. One thing leads to another, step by step. What is the cause here? A spell is akin to a hypnotic effect. In the old movies I watched as a child, the evil hypnotist would say, “You will obey my every command.”

Marie Baniszewski was eleven years old when she testified in court about the murder of Sylvia Likens.

Q. Tell the jury what happened.

A. Mom had scalding hot water running and she told Sylvia to come up from the basement and Mom putted her head under the hot water.

Q. How did she hold her head?

A. By the neck.

Q. By the neck?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Was there any soap on her head at the time?

A. No, sir.

Q. How long did she hold her head under the faucet?

A. Mom did not get to hold her head under there very long because Sylvia was hysterical to get away.

Marie lit the match to heat the poker they used to brand Sylvia. Was she afraid? Just following orders? Hypnotized by her mother’s authority? Did she catch the violence around her as one catches a cold, tuberculosis, the plague? They were all in on it. They slapped, burned, kicked, punched, and laughed. There was a lot of laughing and giggling.

Emotional contagion is alive and well in science. Mention of hypnosis, however, is mostly avoided. Mimesis, that old word, to mimic, imitate, is built in to the species.

Primitive emotional contagion: “The tendency to automatically mimic and synchronize facial expressions, vocalizations, postures, and movements with those of another’s and, consequently to converge emotionally.” (E. Hatfield, J. Cacioppo, and R. L. Rapson, Emotional Contagion, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1993.)

Newborns imitate faces. Parent-infant “synchrony,” coordinated timing between caretaker and baby, from biological rhythms to symbolic exchanges, is a much-studied subject these days. “Developmental outcomes of the synchrony experience are observed in the domains of self regulation, symbol use, and the capacity for empathy across childhood and adolescence.” (Ruth Feldman, “Parent-Infant Synchrony: Biological Foundations and Developmental Outcomes,” Current Outcomes in Psychological Science 16, 2007.) Unconscious imitation begins early before a child speaks. Mothers and infants coordinate heartbeat rates. They are attuned, a unit of reciprocal, mirroring gestures and feelings and sounds and glances.

“The reader should note that for this analysis, the non-rational, non-symbolic transmission of emotional states among individuals is treated as an aspect of information transit among populations.” (James Hazy and Richard E. Boyatzis, “Emotional Contagion and Protoorganizing in Human Interaction Dynamics,” Frontiers in Psychology 6, 2015.)

I see you. I imitate you. I feel what you feel. Think of smiles and yawns. And what about violence?

The epidemiologist Gary Slutkin: “Violence is a contagious disease. It meets the definition of being a disease and of being contagious—that is, violence is spread from one person to another… This paper intends to clarify how violence is acquired and biologically processed.” (National Academy of Sciences workshop, 2013.)

“Social contagion accounted for 61.1% of 11,123 gunshot episodes in Chicago.” The study covered the years between 2006 and 2014. (Ben Green, Thibaut Horel, and Andrew Papachristos, “Modeling Contagion Through Social Networks to Explain and Predict Gunshot Violence in Chicago, 2006–2014,” JAMA Internal Medicine 177, 2017.)

Emotional contagion is alive and well in science. Mimesis, that old word, to mimic, imitate, is built in to the species.The neuroscientist Marco Iacoboni writes, “The missing link between the compelling social science studies on the contagion of violence and the model of such contagion as an infectious disease is a biologically grounded mechanism. A recent neuroscience discovery, a type of brain cell called mirror neuron, may provide such a missing link.” (“The Potential Role of Mirror Neurons in the Contagion of Violence,” National Academy of Sciences, 2013.)

The scientists lay out their facts. Human beings imitate. They converge emotionally. Traveling emotion is information transit. Violence is not like a disease. It is a disease. The confident number 61.1 percent has been divined by an elaborate statistical method. The biological mechanism, the brain machinery underneath it all may be a kind of neuron. But it can’t be at work between violent attacker and victim. If the victim is like me, feels like me, how can I torture and murder her? The victim must be out of the imitation loop. The children mirrored “Gertie” (but not Sylvia) by biological mirror mechanism, an unconscious contagion, by which brutality travels via nonsymbolic information transit? Isn’t this what hipsters in the 1960s called “vibes”?

The marchers in Charlottesville are chanting, “Jews shall not replace us.” They are carrying torches. They are riled up, inflamed in their whiteness and their rage. James Alex Fields drives his car into the crowd and kills a counterprotester, Heather Heyer. The political meaning of this murder is not in doubt.

René Noël Théophile Girard died in 2015. A French native, Girard earned his Ph.D. at Indiana University in 1950. By 1965, when the police found Sylvia’s corpse, he was long gone from the state. He never mentioned the Likens case in his work, although he would have found it pertinent to his thought. Like a number of his countrymen, Girard had a weakness for the bold theory, and he claimed to have unlocked the secret to human violence. It all starts with what he called mimetic desire. The term may be foreign but the phenomenon is easily recognized.

A three-year-old girl skips across the floor in her nursery school and notices a discarded hand puppet on the floor. She bends down, picks it up, and begins to play happily with the nodding, talking mouse at the end of her arm. Another child, who had glanced at the puppet a moment before but had not displayed an iota of interest, watches his schoolmate and finds himself seized with an overwhelming desire for the mouse. He rushes toward her, snatches the thing from her hand, and a puppet war ensues.

Old, dying Mr. F. parades his beautiful young wife in public. His heart is too weak to endure the shock of orgasm, but it is enough that other men look upon him with envy.

Sylvia walks into Gertrude’s house. She is young, pretty, good-natured, and oblivious. Gertrude has asthma, eczema, and seven children. Does she look at the girl and want the impossible: her face, her youth, her innocence?

We are mimetic, imitators deep down. For Girard, all of culture, all social life is about imitation, but it isn’t really the puppet or the trophy wife or the unmarred face that is wanted, according to him; the rival seems to possess some inner quality the other lacks, a shine of wholeness, a magical property that must be wrestled away from her or him at all costs. Viewed from the outside, the two are doubles, mirror images, locked in a contest of desire for what is missing, and that desire leads to vengeful rivalry, which, according to Girard, is contagious. It spreads through the community and can turn into violence.

In Girard’s telling of this big story or myth, and stories this big are always myths, the epidemic can be relieved only by a scapegoat. The bickering, rows, and moral sickness that infect the group are transferred onto a vulnerable or marginal person, someone who has few or no defenders, a person who acts as a sponge to absorb the blame: the witch, the Gypsy, the Jew, the homosexual, the Black person, the Muslim, the immigrant, the epileptic, the beggar, the albino, the crazy person, the female candidate for president, the pretty girl on Facebook. The group does not know that this is what is happening. The group sincerely believes in the outsider’s culpability. Without belief, the scapegoat mechanism cannot work. The chosen one deserves to be punished and, through punishment and death, through the sacrifice of the one, the community emerges cleansed and harmonious once again.

After an eleven-year-old girl hanged herself in my hometown in Minnesota, the rumor circulated that she had been harassed and bullied to death by her classmates. One girl in particular had been the ringleader. The law was never involved, but I remember the gossip that flew through the town, and I remember that the eager telling of the tale was followed by silence and a sense of awe at how terrible it was—a dead child.

Every myth explains too much, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t truths to be found in the story. Girard’s grandiose explanation for human violence unearths part of the truth. Sylvia Likens was a scapegoat.

“This is the chill of an evil essentially collective, social, cultural, even political. It is the site of an old crime, old as the first stone, old as rape and beatings: it is not just murder, it is a ritual killing.” Kate Millett doesn’t mention violence as contagion, or Girard’s theory, but she wants to get hold of the story’s essence and calls it “a ritual killing.” She wants to unearth something true. What does this story mean? How can ritual killings take place without ritual? Or did the woman, the matriarch in that broken-down house, invent rituals from old stories she had heard? “You branded Stephanie and Paula and I am going to brand you.” This sentence attributed to Mrs. B. is repeated several times during the trial. Gertrude Baniszewski was the adult, the leader of the band, the authority in her little world, and she was no longer attached to a man, a higher authority in our world. She was no longer “under his thumb,” as the saying goes. No man was making love to, impregnating, or beating her up anymore. Is her dominant feeling humiliation or does she feel a sudden surge of power or both? “To teach her a lesson,” Mrs. B. said when asked why she “disciplined” Sylvia. “To teach her a lesson.”

There is a picture: a grainy photograph of Gertrude Baniszewski in the newspaper, a gaunt, scowling visage fit for a Grimm brothers’ ogress. She had chronic asthma, and she chain-smoked. During her trial testimony she denied everything. The children had lied to police, had lied on the stand. She moaned about her illness, the drugs she had to take, and how tired she was. She was lying down. She was asleep. She slept through the horrors. The kids must have done it.

There is another picture: a photograph of Sylvia Likens smiling with her mouth closed because she is missing a front tooth her parents couldn’t afford to have replaced. She lost it in an accidental collision with her brother years before. Her eyes are large and lit with vivacity. An article in The Indianapolis Star a week after her death reported, “friends said she was ‘shy’ and she was ‘the odd one in the family.’” Someone probably described her in this way. “Odd one”? Who were these “friends”? Sylvia was born between two sets of fraternal twins. She was literally the “odd” one, a singleton. Her nickname was “Cookie.” She liked to roller-skate. Her favorite band was The Beatles. She was careful with her clothes. She washed and ironed them herself. Her father testified that she had made money ironing for a Laundromat. “She was very good at ironing,” he said. Her mother testified that she was “orderly.” She went to church. She owned a Bible. She was clean. The latter facts came out in the trial, no doubt to prove that she was not a loose tramp but a good, clean, churchgoing, Bible-owning white citizen. And yet, the information about her personality is so scant, all that can be summoned to mind is a smiling vacancy.

From the Trial Transcript of Marie Baniszewski:

Q. What kind of a girl was she before she was beaten up?

A. A real nice girl.

Q. Was she nice to you?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Was she nice to the other children in your family?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Was she nice to your mother?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did she work or help around the house?

A. She always got home before us kids and would straighten up our bedrooms and the downstairs.

I recognize that girl from my own childhood in small-town Minnesota: the nice, helpful, cheerful, orderly girl, willing to serve, the girl who did not make trouble or made as little trouble as she could, the girl who folded her hands on her lap in church and endured the intense boredom of sitting through the service without complaint. This is how Sylvia struck Marie, anyway, as “a real nice girl.” Marie probably liked coming back to a straightened-up bedroom. And yet, “the real nice girl” is also a blank, a type, a nobody.

I was ten years old when Sylvia Likens died, the same age as Marie, the girl who lit the match to heat the poker they used to brand the naked Sylvia, who was tied up, gagged, and held down by Marie’s brother John and her sister, either Stephanie or Shirley. Marie lied stubbornly on the stand to protect her mother, got confused, cried, “Oh, God, help me!” and, after that, slowly began to break under the prosecutors’ examination.

“I know one thing,” Marie said to the prosecutor, “Paula was very jealous of Sylvia.” “Did she say that?” he asked her. “No,” Marie answered. “You could see it in her eyes.” Did they kill her because she was “nice” and “clean”? Was Sylvia an affront, a constant reminder of what the family had lost or was constantly in danger of losing—respectability? The other side of respectability is shame. Shame is not guilt. Shame is what you feel when others look down at you with contempt. Guilt is what you feel when you have internalized the morality of the larger society to which you belong and your conscience prevents you from behaving cruelly to others. Paula, pregnant and shamed, was her mother’s eager, violent enforcer.

The sickness that infects the house on East New York Street cannot be located in a single room or in any one of its residents nor can it be found in the neighborhood kids who come and go freely, in and out, in and out. Like an infestation of vermin, it swarms up the stairs, disappears into floorboard crevices, and crawls inside walls. The whole house is sick with fever, except the girl they have singled out and her sister who drags around a brace on her left leg from infant polio and does nothing, perhaps because she feels there is nothing to do.

From the Trial Transcript of Jenny Likens:

Q. You were perfectly free to go and tell anybody you saw, weren’t you?

A. Yes.

Q. You could’ve told the neighbors about this if you wanted to, couldn’t you?

A. I could’ve. That don’t mean I wanted to die though.

When Sylvia is dead and the police officer arrives at the house, Jenny whispers in his ear, “Get me out of here, and I will tell you everything.”

From a message board, Watching True Crime Stories: General Discussions.

Serene 196936: I am sorry but I have no sympathy for Jenny Likens. I know that’s harsh but I dont

Shar 001: . . . I would have taken Jenny Likens to the side and slapped her iin [sic] the face! She wasn’t some emotionally disturbed 4 year old, you know? I tell yo this my Daughter and her friends age 10 could have gang ed up on those bastards I know this by heart someone you love, your own sister.

The two discussants, true crime watchers, hate Gertrude and Paula and Ricky Hobbs and Coy Hubbard and the neighbor kids who participated in or watched the crimes take place, but they also hate Jenny. They hate her passivity. Sylvia was passive, too, but she is the victim. If Jenny had really loved her sister, she would have acted. Serene and Shar have immersed themselves in the details of the case. They are emotionally involved. They have read the books. They “appreciate” Kate Millett because she is as “passionate” about the Likens murder as they are. The story is a vehicle for their moral indignation. Moral indignation feels good. The imaginary slap serves the imaginary Jenny right. What kind of person looks on while her sister is kicked and burned and used as a living effigy?

From the Trial Transcript of Jenny Likens:

Q. Alright, did you—how many operations did you have on your leg?

A. Approximately six or seven.

Q. When was the last one?

A. When I was thirteen.

Jenny Likens’s polio was not an old story muffled in the amnesia of her babyhood. It was an ongoing drama of hospitalizations. I can only speculate on how this affected her will to act. It was Sylvia who had been her protector.

In September, the girls met their older married sister, Dianna Shoemaker, in a park. They told her that they had been hurt and beaten. Some credit Dianna with alerting social services. Some have speculated that Jenny made the call. According to the trial transcript, the call was anonymous. Some unknown person made a report that there was a child with “open running sores” at 3850 East New York Street. In response, a public health nurse, Mrs. Barbara Sanders, paid a visit to the house. Gertrude informed the nurse that the person she was looking for, the one with the sores, was Sylvia. Gertrude had kicked Sylvia out of the house because Sylvia did not mind and did not take care of herself. In this version of events, Sylvia is not a clean, orderly girl. Sanders recalled “Mrs. Wright” saying that Sylvia had “matted,” “dirty” hair and running sores on her head because she did not wash. Sylvia had called Mrs. Wright’s daughters prostitutes in school, but Sylvia was the prostitute who solicited men in the street. Mrs. Sanders testified that “Mrs. Wright” had claimed her own children were “good children, went to church on Sunday and were not in any kind of trouble and she did not allow them to play with the neighborhood children, she pretty much kept them at home so she knew where they were and so fort…” The nurse seems to have believed this story, and there was no further investigation.

In her book, Millett remembers the Midwest in those days. She was born in 1934—more than twenty years before me—in St. Paul, Minnesota, an hour’s drive from my town of Northfield. Millett identifies with Sylvia intensely in a way I do not. “Because I was Sylvia,” she writes. “She was me. She was sixteen. I had been. She was the terror of the back of the cave, she was what ‘happens’ to girls. Or can. Or might.” Millett also knows she is not Sylvia, admits that the girl often vanishes for her as an imaginative object, but the connection remains. The rigidity of the moral code for girls was matched by the joyous need to condemn the easy make, floozy, tramp, tart, hussy, slut, bimbo, moll, whore. “Aren’t nubile young females responsible in some complicated way for the sexuality they exude?” Millett writes.

“Decency” had a stressful punitive quality for girls in my world, and it was no doubt worse in Millett’s early life. I felt it. Simply reaching sexual maturity brought suspicion in its wake, especially from older women, a suspicion not directed at boys, a suspicion that you were already guilty of something, even before you knew exactly what you were supposed to feel guilty about. But that code began to loosen in my teenage years— idea winds blew across the country and they hit the plains, too. “The double standard” became a phrase.

And the terror at the back of the cave? The stiffening awareness that arrives with a man’s footsteps behind you on the street, the endless stories of rape and brutality meted out by familiars and strangers alike. Millett blames Sylvia’s death on “faith, a series of beliefs, systematic beliefs.” The hatred and shaming of women is alive and well—the threats are everywhere, to rape, behead, hack to pieces feminist bloggers—but when does religious, moral indictment become torture-murder?

Feeling and belief mingle. Belief opens the door to violence, but it may also serve to justify violence after the fact. Irrational hatred attaches itself to ideology. It isn’t just emotion that is contagious, after all. Ideas are caught, too, carried from one person to another, and ideas are used to shore up “identities.” There is no identity without perceived difference. I define myself against you. I am the pure, uncontaminated not-you.

Gertrude tells the nurse that her children are not running wild with the neighbor kids. She doesn’t even let them play with the neighbors. Gertrude’s children are pure of mind and body. They are in church every Sunday. They are never in trouble. It’s that girl, the boarder, Sylvia, the repository for all that is unclean: for literal and metaphorical filth, dirty hair and dirty mind. Gertrude’s intolerable feelings of shame have been dumped onto Sylvia. Gertrude performed “Mrs. Wright” for the nurse.

She acted the part of the good, vigilant, orderly mother, the upright moral citizen who forbids, disciplines, draws a hard line, and brandishes a Bible. To what degree did she believe in this role? Sylvia is the target of furious, if perverse, righteousness. Isn’t the same dynamic at work among some white evangelicals, who spew hatred for dark foreigners of all kinds whom the zealots have loaded up with their own misery and shame?

Nancy Chodorow writes about the psychoanalyst Melanie Klein: “Many of the major political events, crises, and controversies of our time can only be understood if the operation of rage, splitting, projection, and introjection is taken into account. For example, political and cultural demonization of the enemy is psychologically based on projection and introjection, in which all good resides in the nation, the ethnos, the group, and all bad resides in those who are not part of this group. Splitting bad from good… underpins all virulent racism, nationalism, ethnic conflict and attempts at ethnic cleansing or genocide. Splitting may also be used to ward off elements that are threatening because they are too attractive.” She mentions misogyny and homophobia—“attractions and desires that are too anxiety laden to be contained within the self.” (N. J. Chodorow, “Melanie Klein,” in International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, Oxford, UK: Elsevier Science, 2001.)

Larry Craig, former U.S. Republican senator from Idaho, vocal opponent of gay rights, supporter of a 2006 amendment to the Idaho constitution that bans gay marriage and civil unions, is arrested for soliciting gay sex from an undercover cop in an airport bathroom.

“On the campaign trail, you called yourself a nationalist. Some people saw that as emboldening white nationalists…” Yamiche Alcindor, one of the few Black women in the White House Press Corps, asked President Donald Trump on November 7, 2018. He cut her off. “I don’t know why you’d say that, such a racist question.” Swerve and dump.

In her testimony at the trial about her conversation with Nurse Sanders, Gertrude draws a pathetic self-portrait. She recalls the sad condition of her face at the time: “I was wearing sunglasses when I was up because my eyes were swelled and matted quite a bit and my face was swelled and it was raw to the point where it was starting to bleed here and there.” The word matted again, the same word Sanders remembered Gertrude had used to describe Sylvia’s hair—matted. Paula chopped off Sylvia’s hair in uneven hunks. Gertrude pushed her head under scalding water. No soap in the hair. Who and what is matted?

Every one of the actors in the story was poor and white. Sylvia and Jenny’s parents did not fit the description of a fairy-tale couple, but they weren’t a spectacularly wicked pair either. The girls’ mother, Elizabeth Likens, had been arrested for shoplifting. She and her husband had been separated. Lester Likens had trouble keeping a job. They moved a lot, fourteen times in the sixteen years of Sylvia’s childhood. They hit their children. The corporal punishment of children seems to have been a matter of course for everyone involved in the case, one that supports an argument for contagion. Reading the trial transcript, I had the impression that neither the lawyers nor the defendants seemed to believe spankings and whippings were not acceptable punishments. Violence directed at children was natural. The neighbors heard Sylvia screaming for weeks. It was just part of the auditory atmosphere.

The Likenses and the Baniszewskis belonged to what would later be dubbed “the precariat,” people who live from hand to mouth and have far too little financial security to predict their material futures. They make do. But precarious circumstances and hardship do not lead directly or even indirectly to the brutal torture and murder of a teenage girl.

In his book Facing the Extreme: Moral Life in the Concentration Camps (1991), Tzvetan Todorov meditates on heroism, sainthood, and acts of caring that took place among people in the camps who had been brutalized and had every reason to feel hopeless. He describes ordinary acts of kindness to others under extraordinary circumstances, the sharing of food, for example. “Here again,” he writes, “we find a limit beyond which sharing was impossible, simply because hunger and thirst were too great. Once these were even minimally satisfied, however, it seems some shared and others did not.” He cites Eugenia Ginzburg, who wrote a memoir of the eighteen years she spent in Stalin’s prison and labor camps. In her book, she remembers “an old convict [who] brought her some oat jelly he had lovingly prepared but would not eat himself. He was happy just to watch her enjoyment.” I look at your pleasure and it fills me with pleasure—the kind version of mirroring, of empathy. But under conditions of scarcity, of near-starvation, what is it that makes one person hoard food and another share it? Todorov is explicit that caring is to be distinguished from group solidarity and from sacrifice. “Caring,” he writes, “is its own reward, for it makes the giver happy.”

Precarious circumstances and hardship do not lead directly or even indirectly to the brutal torture and murder of a teenage girl.Who are the people who share and who are the people who don’t? How does one know who is who? I have never lived such deprivation. How can I know if I am one or the other? And yet, isn’t it also true that I have been selfish at some moments in my life and generous at others? I have acted bravely, and I have been a coward. Todorov also describes individual acts of kindness and generosity on the part of guards and others in positions of power, people who were during the same period responsible for monstrous acts. What are we? Isn’t this the ultimate question, the question that is terrifying? Do we know? When are we deluded? What about the sadistic urges that everyone feels at one time or another? When do urges become acts?

I remember a girl in my third-grade class with long, unwashed hair that fell in strings across her face, strings she pushed out of her eyes over and over again. It was a tic. She always made herself as small as possible. She sat with her head down and when her fingers weren’t in her hair, they were pressed protectively against her chest as if she were expecting a blow at any moment. When she was called on in class, she whispered. Mostly, I pitied her, but there were times when my sympathy for her paralyzing timidity vanished, and I felt an urge to slap her across the face and shout, “Speak up! Speak up!” I did not hit that girl or yell at that girl, but where is the threshold between thinking and doing? Is it when permission has been given? Is it when a soaring feeling of moral righteousness makes it right and proper to slap? “I would have taken Jenny Likens to the side and slapped her iin [sic] the face!”

“In any case, the condemned man looked so like a submissive dog that one might have thought he could be left to run free on the surrounding hills and would only need to be whistled for when the execution was due to begin.” (Franz Kafka, “In the Penal Colony,” in The Complete Stories, trans. Willa and Edwin Muir, New York: Schocken Books, 1988.)

“Revolution is not a crime! Rebellion is justified!” “Dare to think! Dare to act!” The teenagers were wild with their enthusiasm for Chairman Mao, quoting from the Little Red Book, singing on the buses that carried them from place to place. The fire was in them, a need to purge the pollution of bourgeois thinking from the bodies of the ideologically impure. Slap. Beat. Kick. Burn.

“Because children are often physically vulnerable, easily manipulated, and susceptible to psychological manipulation, they typically make obedient soldiers.” (Human Rights Watch, “Coercion and Intimidation of Child Soldiers to Participate in Violence,” www.hrw.org/en/topic/childreno39s-rights/child-soldiers.)

No one helped Sylvia. No one performed an act of caring for its own reward. None of the children, as far as I know, slipped her food or water or treated her wounds, much less ran off to seek help for her. No adult who visited the house was softened by sympathy either. An adult neighbor, Mrs. Vermillion, who lived at 1848 East New York Street, testified that she had seen Sylvia with a black eye Paula bragged about having given her. She had seen Paula throw hot water in Sylvia’s face and rub garbage into it. She had heard Gertrude say she hated Sylvia. Mrs. Vermillion testified that Sylvia had “looked scared,” that she didn’t seem to care whether she lived or died. Mrs. Vermillion did nothing. The family pastor, Roy Julian, visited the house several times, a man whose testimony at the trial demonstrated not just his willingness to swallow lies about the nasty Sylvia but his tacit approval of severe “correction” for wayward children, an approval that hung over the neighborhood like a lowering cloud.

Sylvia’s “difference” in that house was not a class, ethnic, religious, or ideological difference. She was not in the Baniszewski family, not blood, not Gertrude’s child. Not mine. Theirs. This was perhaps enough. “Come on, Sylvia, try to fight me.” But Sylvia did not fight back. Girls did not stage fights in the little world of my Northfield childhood. Wounding words, cruel gossip, hurtful notes left in lockers, hateful phone calls were routine. The occasional slap happened, but the only real violence I witnessed was among boys. Girls do fight in other worlds, however, and they take pride in defending their turf. They have a moral code that gives them permission.

“Sharon explains how the ferocity of Sophie’s temper meant that she quickly got the better of the other girl; Sophie had quickly knocked her opponent unconscious and then dragged the girl by the hair to a nearby parked car, smashing her head through the windscreen. Sharon laughs because she can see how horrified I am by the story and in a vain attempt to reassure me, she emphasizes that girls don’t fight as much as boys.” (Gillian Evans, Educational Failure and Working Class White Children in Britain, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.)

The neighborhood children came and went in the house, an intermittently violent horde Gertrude pretended she monitored closely while she was playing her alter ego, “Mrs. Wright.”

During the trial Gertrude was asked about the child traffic by her defense lawyer.

Q. Did you ever tell them to stay away?

A. Yes, I did many times. I would try to lock the doors and Paula would—you know chase them out or chase them away because—I mean I was to the point where I could not stand noise or anything anymore. It was, I just could not take it anymore. I had everybody’s children.

But Sylvia was the only child forced to eat the family’s demons. “It is always possible to bind together a number of people in love,” Freud wrote in Civilization and Its Discontents, “as long as there are other people left over to receive the manifestations of their aggressiveness.”

A worn face crusted with sores in the mirror, old before its time. Memories of a man’s flying fists visit every room. A belly swells with the inevitability of another life. Slut. An infant squalls. Wheezing. Laughter. Cigarette smoke. Young voices inside and out. The screen door opens and slams shut. And the undefiled border blooms with seductive promise as she sings to herself and carefully irons her blouse for school.

The only letter the woman they called “Gertie” had the strength to impress with a burning needle on the girl’s body is the capital letter I. Then she gave the task to her lackey, Richard Hobbs, who finished the job but needed help spelling the word prostitute. “I am a prostitute and proud of it.” The crime of sex work was written onto Sylvia Likens’s body, but to whom did that wandering “I” belong? Who owned it? Is this the problem? Who is “I”? The irony is fierce. The frenzied effort to blame and brand the other, to build a wall between self and other, collapses. What is “me” and what is “you”? But the commonality is visible only from the outside. Girard writes, “The proper functioning of the sacrificial process requires . . . the complete separation of the victim from those beings for whom the victim is a substitute.” (Violence and the Sacred, trans. Patrick Gregory, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1977.)

Gertrude Baniszewski had been pregnant thirteen times. Six of the pregnancies ended in miscarriage. Paula’s pregnancy had become obvious, but it was Sylvia they insisted was with child. Over and over they told her she was pregnant, and once, after someone belted her in the stomach, Sylvia grabbed herself around the middle and said, “My baby.”

Who’s who in this game?

Once Gertrude had looked ahead toward the fuzzy but hopeful geography of the future, a place reached by means of one thing only: sexual allure. Without education or money, this was a girl’s ticket to Somewhere through Someone, but that ticket is as dated as a package of meat. This is a contagious thought, surely, an idea that survives in a culture of female beauty worship that may easily take on a quality of desperation. Gertrude was sixteen when she married John Baniszewski, exactly Sylvia’s age; Sylvia, who but for a missing tooth was hale and whole and perfect when she first came to stay in the house and her future had not yet been written.

But it’s very late in the story now, and the woman must admit to herself that the girl’s traveling carnival parents might return any day or the law might get wind of the indoor blood sport that has been so popular at 3850. What reasonable explanation can be given for the child’s ruined body? She does not even “look human anymore.” The game has become war. The woman dictates a letter to the girl for her parents. Obediently, the girl writes, “Dear Mr. and Mrs. Likens.” The woman is blind to the mistaken mode of address. Is she panicked or seized by some other fundamental confusion? Who is writing? The woman invents a tale about roving boys with whom the girl had sex for money, boys who then beat her and cut the sentence into her, a ready narrative stolen from the tabloids, and the girl writes this down, but the girl’s hand no longer belongs to her. The pencil moves across the page and forms the letters of the words: “I have done just about everything I could to make Gertie mad and cost Gertie more money than she’s got. I’ve tore up a new mattress and peed on it. I have also cost Gertie doctor bills that she can’t pay and made Gertie a nervous wreck and all her kids.” The letter is not signed.

No, Gertrude Baniszewski was not a clever criminal who plotted the perfect crime. She was not one of those steely psychopaths of fiction so admired by millions of readers and moviegoers. She did not outwit or outthink anyone, but the absurd letter reveals her malignant narcissism nevertheless. It’s all about Gertie all the time. She is the queen of 3850, despot for the moment, the one who gives orders: Take a letter. And there is never any evidence of guilt. Gertrude’s crowd is a small one, but it’s a crowd nevertheless. And this is the woman into whom all the suspects’ identities have merged. The monster criminal is a hydra with many heads. The criminal is Gertie-and-the-kids, a collective nervous wreck acting in concert like a swarm of bees or a flock of geese, and Sylvia, the scapegoat, is part of them, too, isn’t she? Isn’t her body the site of their cast-out demons? Who is having the baby?

Is this the fable I have been looking for? Politics writ small?

In I See Satan Fall Like Lightening (1999), René Girard writes, “The torture of a victim transforms the dangerous crowd into a public of ancient theater or modern film as captivated by the bloody spectacle as our contemporaries by the horrors of Hollywood. When spectators are sated with that violence Aristotle called ‘cathartic’—whether real or imaginary it matters little—they all return peaceably to their homes to sleep the sleep of the just.”

When the task of the lynch mob is finished and the mutilated body of the Black woman or Black man hangs from a tree, a calm descends on the frenzied throng of whites and unanimity reigns.

After the rally, after the full-throated joy and venom of “Lock her up!” or “Send her back!” the crowd disperses and they climb into their cars to drive home appeased and smug that justice has been done.

I do not think the gang at 3850 would have tortured a boy, not a white, straight, healthy boy, anyway. No, it had to be a girl in this particular hierarchy in this particular story at this particular time and place, in which a brutal morality of feminine purity serves as the whip that transforms the clean, obedient, passive virgin into the filthy, rebellious, actively malevolent whore.

In the last hours of her life, Sylvia tried to run from the house, but was dragged back by Gertrude and, later, she tried to alert the Vermillions by scraping a shovel on the basement ceiling. Mrs. Vermillion testified she heard “hollering” and “scraping noises” from the basement next door the night before Sylvia died, that she and her husband went out to investigate and threatened to call the police. They did not call. The scraping sound stopped. Close your eyes. Plug up your ears. It will go away.

From The Indianapolis News, May 2, 1966:

The sobbing sister of Sylvia Marie Likens today quoted her as saying, “Jenny, I know you don’t want me to die. But I’m going to die. I can tell.”

John Baniszewski, Coy Hubbard, and Richard Hobbs were convicted of manslaughter with varying sentences from two to twenty-one years. All three were released after eighteen months in a reformatory. Paula, convicted of second-degree murder, was paroled after serving two years. Not long in a country with the largest prison population in the world, but the punitive lock-them-up-for-everything-and-anything policies and their barely disguised racism that resulted in the mass incarceration of Black men did not begin until the 1970s. And this is a white story, so the youngsters who committed these acts were treated as children, not monsters.

The house at 3850 East New York Street was demolished in 2009, but before then it was a featured destination on Historic Indiana Ghost Walks and Tours. “Explore the undead underbelly of Indiana’s most haunted places with Indiana’s most accomplished professional paranormal investigators.” Sylvia Likens is surely a ghost, with or without “professional paranormal investigators.” She lives on in the stories and in the books and in the true-crime watchers and in me because the case is fascinating and terrifying, and because I do not think it is as aberrant or unusual as is comforting to believe.

“The people of the world do not invent their gods,” Girard wrote. “They deify their victims.”

For some, Sylvia Likens is a martyr to the cause of ending child abuse. Thou shalt not torture and murder children. To others she is a saint—not a real one, of course. The girl wasn’t even Catholic, and miracles are required. And yet, the torture she endured seems to qualify her for some status beyond ordinary mortal. Saint Agnes was stripped, thrown into a brothel, and tortured. Legend has it that they cut off her breasts, which in the iconography she sometimes carries on a plate. St. Agnes’s faith was resolute, and her hymen remained unbroken.

One of Sylvia’s fans online, MichaellovesSylvia, wrote, “I’m not an overly religious person but Philomena has always been my favorite saint and she is the one I most closely associate with Sylvia.” It seems that this third-century Greek princess refused the advances of Emperor Diocletian and was sentenced to death. She died at thirteen, her virtue intact, but she was awfully hard to kill. Time after time, angels intervened to save her life, but their ministrations did not prevent her horrific pain. She was lashed bloody, cast into the sea to drown, shot full of arrows, and finally died when they chopped off her head. They say her grave was discovered in 1802. Inside it were her tiny brittle bones and a small vial of dried blood.

People like stories that make sense. Virtue rewarded. Poor Philomena may have left this earth headless, but the angels carried her broken body up toward the firmament, and, as they ascended, a celestial choir sang harmonies never heard before by human ears. Down here among the living, things are not so simple. The scapegoat mechanism is churning away among us. I feel it and I see it in others. Girard writes, “Each person must ask what his relation to the scapegoat is. I am not aware of my own, and I am persuaded the same holds true of my readers. We have only legitimate enemies.” I must ask myself. Was the timid girl in my third-grade class enacting exactly what I most hated in myself—my own fear of authority, my own failures to speak up when I should have? The crowd gathers at a rally or it forms online. It bellows with one voice. It has its reasons. It is rife with pious feelings and honorable proclamations, and then it turns on its victim.

____________________________________________________________

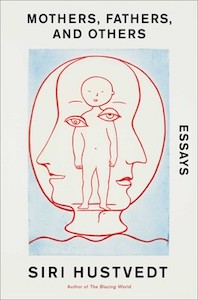

From Mothers, Fathers, and Others. Used with the permission of the publisher, Simon & Schuster. Copyright © 2021 by Siri Hustvedt.