Book Bans Are Targeting the History of Oppression

The possibility of a more just future is at stake when young people are denied access to knowledge of the past.

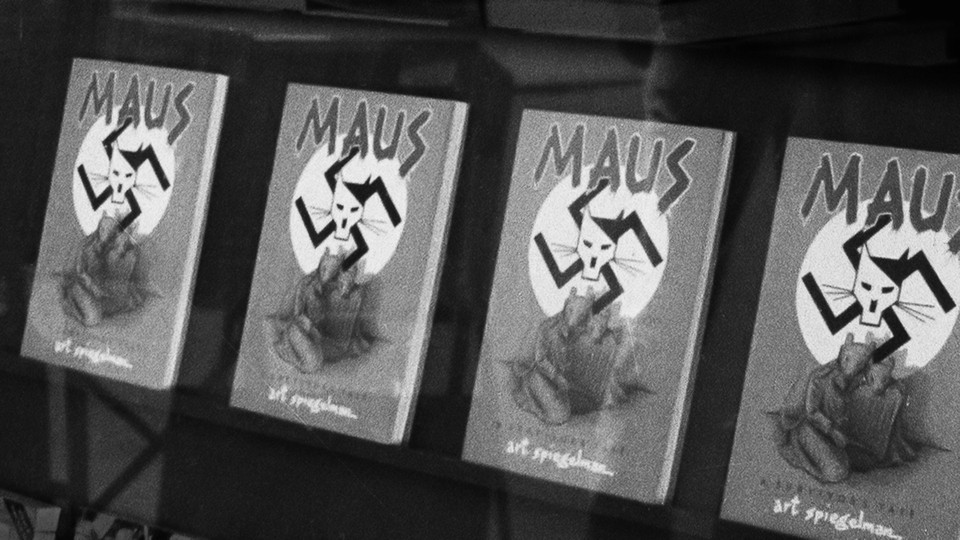

The instinct to ban books in schools seems to come from a desire to protect children from things that the adults doing the banning find upsetting or offensive. These adults often seem unable to see beyond harsh language or gruesome imagery to the books’ educational and artistic value, or to recognize that language and imagery may be integral to showing the harsh, gruesome truths of the books’ subjects. That appears to be what’s happening with Art Spiegelman’s Maus—a Pulitzer Prize–winning graphic-novel series about the author’s father’s experience of the Holocaust that a Tennessee school board recently pulled from an eighth-grade language-arts curriculum, citing the books’ inappropriate language and nudity.

The Maus case is one of the latest in a series of school book bans targeting books that teach the history of oppression. So far during this school year alone, districts across the U.S. have banned many anti-racist instructional materials as well as best-selling and award-winning books that tackle themes of racism and imperialism. For example, Ijeoma Oluo’s So You Want to Talk About Race was pulled by a Pennsylvania school board, along with other resources intended to teach students about diversity, for being “too divisive,” according to the York Dispatch. (The decision was later reversed.) Nobel Prize–winning author Toni Morrison’s book The Bluest Eye, about the effects of racism on a young Black girl’s self-image, has recently been removed from shelves in school districts in Missouri and Florida (the latter of which also banned her book Beloved). What these bans are doing is censoring young people’s ability to learn about historical and ongoing injustices.

For decades, U.S. classrooms and education policy have incorporated the teaching of Holocaust literature and survivor testimonies, the goal being to “never forget.” Maus is not the only book about the Holocaust to get caught up in recent debates on curriculum materials. In October, a Texas school-district administrator invoked a law that requires teachers to present opposing viewpoints to “widely debated and currently controversial issues,” instructing teachers to present opposing views about the Holocaust in their classrooms. Books such as Lois Lowry’s Number the Stars, a Newbery Medal winner about a young Jewish girl hiding from the Nazis to avoid being taken to a concentration camp, and Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl have been flagged as inappropriate in the past, for language and sexual content. But perhaps no one foresaw a day when it would be suggested that there could be a valid opposing view of the Holocaust.

In the Tennessee debate over Maus, one school-board member was quoted as saying, “It shows people hanging, it shows them killing kids, why does the educational system promote this kind of stuff? It is not wise or healthy.” This is a familiar argument from those who seek to keep young people from reading about history’s horrors. But children, especially children of color and those who are members of ethnic minorities, were not sheltered or spared from these horrors when they happened. What’s more, the sanitization of history in the name of shielding children assumes, incorrectly, that today’s students are untouched by oppression, imprisonment, death, or racial and ethnic profiling. (For example, Tennessee has been a site of controversy in recent years for incarcerating children as young as 7 and disrupting the lives of undocumented youth.)

The possibility of a more just future is at stake when book bans deny young people access to knowledge of the past. For example, Texas legislators recently argued that coursework and even extracurriculars must remain separate from “political activism” or “public policy advocacy.” They seem to think the purpose of public education is so-called neutrality—rather than cultivating informed participants in democracy.

Maus and many other banned books that grapple with the history of oppression show readers how personal prejudice can become the law. The irony is that in banning books that make them uncomfortable, adults are wielding their own prejudices as a weapon, and students will suffer for it.