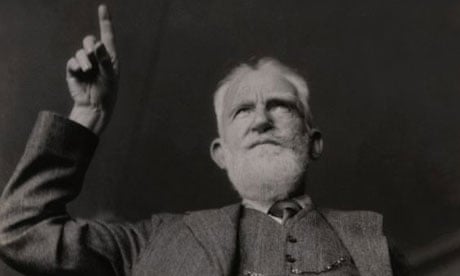

Herbert Beerbohm Tree and George Bernard Shaw were not obviously compatible men. Tree was the actor-manager who brought Shakespeare to the West End, supported playwrights, founded Rada and specialised in outrageous bombast, trowelled-on greasepaint and practical jokes. Shaw was teetotal, vegetarian, passionately political and had switched from being a starstruck critic to a painstaking playwright, taking eight long years to produce his "first and worst" play, Widower's Houses. He wrote Pygmalion as a gift for Stella Patrick Campbell, a capricious, raven-haired, bewitching star he loved "violently and exquisitely". On reading the play, she wrote thanking him "for thinking I can play your pretty little slut"; she was flattered, too, as Eliza was 30 years her junior. Tree would play Higgins and also direct.

Rehearsals were stormy. Shaw yelled at Tree for being "so damned treacly!" and wrote irate letters. Tree scribbled in his notebook, "I will not go so far as to say that all people who write letters of more than eight pages are mad, but it is a curious fact that all madmen write letters of more than eight pages." Just before the dress rehearsal, Campbell disappeared to get married secretly.

The press swarmed about the theatre, and Tree gave an impromptu press conference, lying that he had known all about the wedding. He also had to contend with questions on the play; all London knew that Eliza was scripted to cry out: "Not bloody likely!" The Daily Sketch speculated on the "forbidden word... Will Mrs Patrick Campbell speak it? Has the censor stepped in, or will the word spread? If he does not forbid it then anything might happen!" When Campbell did pronounce the "incarnadine adverb" (as the Daily Mail fastidiously put it), the audience laughed for a full 75 seconds. Appalled by the shallow response, Shaw stormed off.

The word was denounced by preachers, politicians and by a genuine flowergirl the Daily Express took to the play and then bribed with several pints of milk stout to say that the language was shocking. Campbell, on the other hand, was "just luvly - but she was not altogether what you might call true ter life. As for Bernard Shaw, well, he thinks a blooming sight too much of himself, he does." Another audience member wrote to the Sandwich Gazette to lament: "Ever since Mr Shaw flung his unprintable word at the play-going public, my wife, who is a refined and educated woman, has regarded it as a huge joke to use this expletive... May I ask whether one's sense of humour is likely to be still further strained?"

The critics were less prurient. The Daily Sketch judged the word "absolutely appropriate... and Mrs Patrick Campbell's consummate comedy acting robs the phrase of all offensiveness". Other critics speculated on whether Tree was lampooning someone famous, "Sir Herbert is made up to an astonishing likeness to Lord Northcliffe," asserted the Times, while the Northern Echo observed that "Sir Herbert contrives to resemble Mr Asquith" and the Observer thought he looked "exactly like Mr Winston Churchill". Overall, though, the verdict was that Pygmalion - the first of Shaw's plays to become a popular hit - was, as the Daily Telegraph put it, "the jolliest stuff".

Mollified, Shaw returned for the play's 100th performance, but was horrified to find that Tree had changed the ending; Higgins now threw Eliza a bouquet as the curtain fell, presaging their marriage. Now that his affair with Campbell was over, the romantic ending was particularly galling. "My ending makes money; you ought to be grateful," scrawled Tree. "Your ending is damnable; you ought to be shot," snarled Shaw. Tree would have been pleased to know that the musical, My Fair Lady, retained and extended his ending. Shaw might well have been horrified at seeing his argument for social mobility reduced to what may have been his secret subtext: a love-letter to the woman who spurned him.