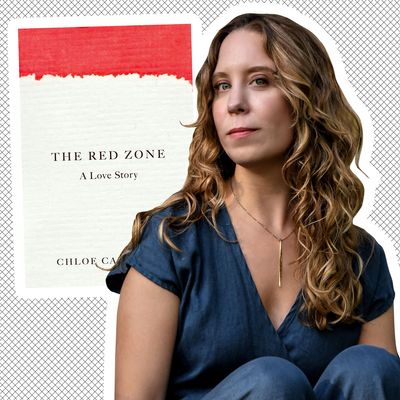

Chloe Caldwell’s new book, The Red Zone: A Love Story, is all about her period (see the red-soaked cover). More specifically, Caldwell — author of the novel Women and essay collection Legs Get Led Astray — has premenstrual dysphoric disorder, or PMDD, a little understood and very severe form of PMS. It’s unknown what exactly causes PMDD; like so many health conditions primarily affecting women, the disorder is under researched. In writing her book, Caldwell wanted to provide a case study. It may not be like this for everyone, but this is what PMDD is like for her: debilitating pain and fatigue, cystic acne, paranoia, severe irritability, and “massive outbursts.”

Characteristically affecting, sharp, and funny, The Red Zone is also (per its subtitle) a love story about Caldwell’s relationship with Tony, her now-husband, and Sadie, her stepdaughter. Because Caldwell started learning more about PMDD at the same time she started dating Tony, the two threads intertwine, sometimes messily, as she’d be the first to admit — like the time she texted him a picture of her blood clots while he was making breakfast, which he asked to finish first. Here, Caldwell talks to the Cut about her experience living with (and writing a book about) PMDD.

What made you want to write a book about PMDD?

It was easy to decide I wanted to write about PMDD; it’s what I was experiencing. It was what I was thinking about and what I was talking a lot about. When you write nonfiction, if you’re thinking and talking about something all the time, there’s usually something there. I was into the challenge. PMDD is so mental, and I had never seen it depicted in literature or memoir. There are a few scientific books about it, but that’s it. I knew it would be challenging, because it’s such a tough thing to describe to people without looking like you’re “crazy.” But I knew I wanted to see a memoir about someone’s period, because I had never seen one. And I was like, Okay, well, everyone already thinks that I’m this person who writes all this personal stuff about their life, so I might as well take that and run with it — like, “Oh, you thought I wrote personal stuff then? Well, what if I write a book about my period?”

For those who aren’t familiar, what’s the difference between PMS and PMDD?

PMS is the natural cycle that’s supposed to happen. Of course, we’re going to feel different every couple weeks with our changing hormones, because we live in these phases that people who don’t get their periods don’t live in. With PMS, maybe some months it’s more prevalent and some months it’s really subtle. But it’s what’s supposed to happen – you feel a little bit antisocial, irritable, tired, and introverted. PMS doesn’t disrupt your life and your relationships, whereas PMDD starts to affect people’s work, their marriages, their relationships, their friendships. It’s much more obvious, and it’s actually dangerous.

PMDD is still really controversial. I’m thinking about the Catherine Cohen joke from her new Netflix special. When she’s talking about PCOS (polycystic ovary syndrome, a hormone disorder), she has this joke where she’s just like, “Yeah, everything we know about women’s disorders online is just like, ‘We don’t know.’” That’s exactly it with PMDD — people still don’t know why it happens.

I think it’s challenging, as a feminist, to know how much to acknowledge one’s period. You don’t want to give it too much power or say that it’s incapacitating, because then people might think women can’t do things. But on the other hand, it doesn’t feel fair to not acknowledge the effects it has. How did you reckon with that?

After thinking about that for a couple years while writing this, I now stand by the fact that anyone who’s going to tell another person to shut up about their period or say that what they’re experiencing isn’t real — that’s just not cool. No one who has PMDD and has suffered from it would ever want it or wish it on anyone. I think the feminist standpoint is to let each person have their experience.

I feel that periods are powerful. I think that sharing my struggle with PMDD gives my period good power. It’s good to honor those cycles and teach people around us to honor them. I have a stepdaughter. I think it’s important to tell her, “Hey, if you don’t feel good and you have cramps, it’s okay to say, ‘You know what? I don’t feel good. My body is doing this thing, and I’m actually gonna go lie down.’”

You were very careful to use gender-inclusive language around periods, which is important, especially because periods have become a favorite topic for TERFs. Maybe it’s awkward to say “menstruators” for people who get their periods, but saying it’s just women (or all women) isn’t accurate. How did you approach the evolving thinking around this subject?

It used to be so binary — “Men are from Mars; women are from Venus.” “Women get their periods; men don’t.” I have some interviews in a chapter called “The Linen Closet” with a few trans and nonbinary people, because that gendered piece of it was on my mind. I remember a trans friend getting his period with me once, and I never forgot that. I have another friend who was like, “Can’t women just have this? This is something that has really bonded women, and there’s something special to that.” But you can’t look at someone and know if they have a period or not. I feel each person should get to use whatever terminology they’re comfortable with.

In your book, you cite a few excerpts from Reddit. I wonder what finding that community has done for your experience of PMDD.

I love Reddit. I feel like this book could have been called Reddit: A Love Story. At first, I used it for acne advice. It helped me clear up my skin. (My acne was in conjunction with my period.) Then, when I found out what PMDD was, I looked that up on Reddit and found the ”Werewolf week” group. I was so relieved. I couldn’t talk to anyone else who was experiencing PMDD in person, because I didn’t have any friends at the time who had it. So I would go to Reddit and just read everything.

When I was in a better mood and reading it with my husband, it was actually really healing to hear people’s experiences, because when you have distance, there are funny parts. I think there are TikTok people and there are Reddit people. I’m all Reddit. I can find any community there — no matter how specific it is. I love that.

You referenced worrying that people will think you’re crazy because of this book. How much of your relationship with your husband figured into that worry? Were you worried people would judge your relationship and the way your PMDD affects it?

There are definitely other versions of this book that he is less of a character in, but, over time, the book developed into a richer memoir. In a memoir, you really need characters, and he is a big part of this story, so I succumbed to that. Luckily, he’s the kind of person who totally rolls with it and thinks the book is hilarious. He has read it a bunch of times, so that definitely made it easier. My worry was that I was going to come off as the neurotic, crazy writer and he as the stable partner. I don’t feel that’s our story. I wanted to protect our relationship, so I mostly kept our relationship in the book PMDD-specific and left out a lot of the other stuff.

What do you wish more people who are getting their periods, or who already have their periods, knew about menstruation? Or what do you wish you had known when you first got yours?

I actually asked a friend that, and she said, “I wish I had known that it was completely different for each person.” You go to the doctor, and they’ll ask, “Is your period heavy or light?” And you’re like, “I have no idea. I don’t know who to compare it to.” I’m 36, and when I grew up, it was kind of like the blind leading the blind. One of my friends was stapling pads to her underwear. I’m not trying to say everyone should be loud and proud about their period. Everyone has a different comfort level. But I just want to lay out the options and the choices, which people have more of now. There’s even period underwear now!