Joan had to look beautiful.

Tonight there was a wedding in goddamned Brooklyn, farm-to-table animals talking about steel-cut oatmeal as though they invented the steel that cut it. In New York the things you hate are the things you do.

She worked out at least two hours a day. On Mondays and Tuesdays, which are the kindest days for older single women, she worked out as many as four. At six in the morning she ran to her barre class in leg warmers and black Lululemons size 4. The class was a bunch of women squatting on a powder-blue rug. You know the type, until you become one.

*

Forty-two. Somehow it was better than forty-one, because forty-one felt eggless. She had sex one time the forty-first year, and it lopped the steamer tail off her heart. After undressing her, the guy, a hairless NYU professor, looked at her in a way that she knew meant he had recently fucked a student, someone breathy and Macintosh assed, full of Virginia Woolf and hope, and he was upset now at this reedy downgrade. Courageously he regrouped, bent her over, and fucked her anyhow. He tweaked her bony nipples and the most she felt of it was his eyes on the wall in front of her.

The reason the first part of the week is better for older single women is that the latter part is about anticipating Rolling Rocks in loud rooms. Anticipation, Joan knew, was for younger people. And on the weekends starting on Thursday young girls are out in floral Topshop shirts swinging small handbags. They wear cheap riding boots because it doesn’t matter. They’ll be wanted anyway; they’ll be drunkenly nuzzled while Joan tries ordering a gin and tonic from a female bartender who ignores her or a male bartender who looks at her like she’s a ten-dollar bill.

But on Mondays and Tuesdays older women rule the city. They drizzle orange wine down their hoarse throats at Barbuto, the dressed-down autumn light coming through the garage windows illuminating their eggplant highlights. They eat charred octopus with new potatoes in lemon and olive oil. They have consistent bounties of seedless grapes in their low-humming fridges.

Up close the skin on Joan’s shoulders and cleavage was freckled and a little coarse. For lotion she used Santa Maria Novella, and her subway-tiled bathroom looked like an advertisement for someone who flew to Europe a lot. When her pedicure was older than a week in the winter and five days in the summer, she actually hated herself. The good thing about Joan was, she wasn’t in denial. She didn’t want to love charred octopus or be able to afford it. But she did and she could. The only occasional problem was that Joan liked younger guys. Not animalistically young like twenty-two. More like twenty-seven to thirty-four. The word cougar is for idiots, but it was nonetheless branded into the flank steak of her triceps.

Now Joan knew the score. For example, she was never one of those older women who is the last female standing at a young person’s bar. She didn’t eat at places she didn’t have a reservation or know the manager. For the last decade she’d been polishing her pride like a gun collection. She no longer winked.

In the evenings she would attend a TRX class or a power yoga class or she would kickbox. Back at home before bed she freestyled a hundred walking lunges around her apartment with a seven-pound weight in each hand. She performed tricep dips off the quiet coast of her teak bed. She wore short black exercise shorts. She looked good in them, especially from far away. Her knees were wrinkled, but her thighs were taut. Or her thighs were taut, but her knees were wrinkled. Daily happiness depended on how that sentence was ordered in her brain.

In a small wooden box at her nightstand she kept a special reserve of six joints meticulously rolled, because the last time she’d slept with someone on the regular he’d been twenty-seven and having good pot at your house means one extra reason for the guy to come over, besides a good mattress and good coffee and great products in a clean bathroom. At home your towels smell like ancient noodles. But at Joan’s the rugs are free of hair and dried-up snot. The sink smells like lemon. The maid folds your boxers. Sleeping with an older woman is like having a weekend vacation home.

In addition to the young girls, Joan envied also the women who wake at three a.m. to get stuff done because they can’t work when the world knows they’re awake. They have, like, six little legs at their knees. She told her therapist as much, and her therapist said, That’s nothing to be envious of, but Joan thought she could detect a note of pride in the voice of her therapist, who was married, with three small children.

Tonight there was a wedding and she had to look beautiful. She needed a blowout and a wax and a manicure and a salt scrub and an eyelash tint, which she should have done yesterday but didn’t. She needed five hours, but she only had four. She needed cool hairless cheeks. She was horrified by how much she needed in a day, to arrive not hating herself into the evening. She knew it wasn’t only her. Everything in Manhattan was about feeding needs. Sure, it had always been like that, but lately it seemed like they took up so much brain estate that a lady hardly had enough time to Instagram a photo of herself feeding each need. Eyelash tinting, for example. Nowadays if you have a one-night stand you can’t run into the bathroom in the morning to apply mascara. It’s expected that your eyelashes are already black and thick as caterpillars. be nice to you, said signs outside Sabon on the way to Organic Avenue. But the problem, Joan knew, was that if you be nice to you, you get fat.

The twenty-seven-year-old caught her plucking a black wiry hair out of her chin, like a fish dislodging a hook from its own face. The bathroom door was ajar and she saw his eyeball out of the corner of her degradation. That was the last time he slept over. He had single-position sex with her two weeks later, but he didn’t sleep over and he never texted after that. She remembered with bitter fondness the Dean & DeLuca chicken salad she fixed him for lunch one day, the way he took it to go like someone who fucked more than one woman a week. The more a man didn’t want her, the more it made her vagina tingle. It was like a fish that tried to panfry itself.

*

Twenty-seven. When Joan was twenty-seven she had started waking with the dry-socket dread, the biological alarm that brinnggs off at four a.m. in nice apartments. The tick tick salty tock of eggs hatching and immediately drying upon impact, inside the choking cotton of a Tampax Super Plus. She would wake in an Irishy-weather sweat, feeling lonely and receiving wedding invitations from girls less pretty than her. More than she wanted kids, she wanted to be in love. But Joan had done better in her career than almost everyone she knew. For example, she had started pulling NFL players out of hats during Fashion Week, when her friends were leaving Orbit wrappers in the back rows of Stella McCartney.

She could have had a man and a career. It wasn’t that she chose one over the other. No woman ever chose a career over having a man’s prescription pills in her medicine cabinet. But Joan didn’t like anyone who liked her. The guys who liked her were mostly smart and not sexy and she really wanted someone sexy. She would even have been OK with chubby and sexy, but the chubby sexy guys were all taken. They were thirty-four and dating twenty-five-year-olds with underwire bras and smooth foreheads. The problem was Joan’s generation thought they could wait longer. The problem was, they were wrong.

*

Thirty-four. When she was thirty-four she dated a man who was forty-six, who wore Saks brand shirts and had sunken cheeks and a money clip. They ate at the bars at great restaurants every night, but then she had sex with a gritty LES bartender and she did it without a condom on purpose. Mr. Big, her friends called the forty-six-year-old. They said, What’s wrong with James? He’s ahmaayzing. They said amazing in a way that meant they’d never want to ride him. The bartender gave her gonorrhea, which she didn’t even know still existed, and it made her feel older than her mother’s chewed Nicorette gum, frozen in time and lodged like the miniature porcelain animal figurines, seals and bunnies, that had been left inside the old lady’s old Volvo. The same Volvo Joan still kept in the city, because having a car in the city means you can kill yourself gently if you really must. If something awful happens, you have a car, you can get the fuck out. Tonight there was a wedding and she had to look beautiful because she was in love with the groom. It was the kind of love that made her feel old and hairy. It also made her feel alive.

He was an actor who was thirty-two. She first noticed him across the room at a party because he was wildly tall. He had a grown-up look, but he was also a kid. He was good at drinking beer and playing baseball. That was something she realized now that Mr. Big didn’t have, the tufted Bambi plush of youth to make her feel bad. She must like feeling bad somewhat. Everybody did, but she might like it a little more than most.

He was at the bar, so she sauntered over. She walked with her butt light behind her and her boobs pendulous in front of her. She’d learned the walk from a pole-dancing workout class she’d been taking before a superhot twenty-four-year-old brunette with sharp dark bangs started taking the class and even the other women looked like they wanted to fuck her. Why, Joan wondered, were other women her age complicit in appreciating youth?

She ordered a Hendrick’s because that was what she ordered when she was trying to get a younger guy to notice her. A grandfather clock of an older woman drinking Hendrick’s was a Gatsby sort of thing. It made men feel like Warren Beatty, to drink beside one.

Hendrick’s, huh? he said on cue. One thing good about being forty-two was that she had eaten enough golden osetra to be able to predict any party conversation.

Jack had noticed her from across the room also. She was wearing one of those thick crepe red dresses that women her age wore to play in the same league as twenty-something girls in American Apparel skirts.

—Hendrick’s, for the long and short of it, she’d said in a husky voice, holding the cool glass up to her bronzed cheek like a pitch-woman. There was something freakishly hot about an older woman who wanted it. He imagined her in doggy style. He knew her thighs would be superthin and also she would be kind of stretched out so fucking her would be a planetary exercise, like he was poking between two long trees into a dark solar system and feeling only wetness and morbid air.

That had been eight months ago. An entire summer passed and summers in Manhattan are the worst, if you’re single and in love with someone who isn’t. If you’re older and single and the younger man you are in love with is not on Facebook, but his even-younger girlfriend is.

Her name was Molly. She had a hundred brothers. Her youth was brutal.

Joan learned about Jack and Molly from Facebook. It made her feel creepy and old to click into Molly’s friends and go through each of their pages one by one to see if one of them had a different photo of Jack. Jack wasn’t on Facebook, which Joan loved about him.

Thursdays through Saturdays Joan played with the recurrent hair under her chin and moused through Molly’s life. She found out information, which is all any woman wants. Some of the information waggled her belly and chopped up her guts into the blunt mince of the sweetbreads she orders at Gramercy Tavern. Like for example Joan found out that a few months prior, when Jack had invited Joan out for an unusual Friday night dinner, it was because Molly had been in Nantucket with some friends. She saw the pictures of furry Abercrombie blondes and one brown-haired girl on a lobster boat, fresher than a Tulum mist. Joan got super-pissed about that. Then she tucked an Ambien down her throat like a child into bed and reminded herself that they weren’t even having an affair.

The most that had ever happened was, they kissed.

The kiss happened at The Spotted Pig, on the secret third floor where Joan was at a famous producer’s party and texted Jack to see if he wanted to come by and he brought his friend Luke, who looked at her like he knew what her nipples tasted like.

Joan drank Old Speckled Hen and didn’t get drunk and Jack drank whiskey until he became a little more selfish than usual. She was wearing a slip dress and Luke left with some twenty-two-year-old and Jack put his large hand on her silk thigh, and then she took his hand and slipped his thumb under the liquidy lip of the dress and he got a semi and kissed her. His tongue licked the hops off her tongue. She felt like she had eighteen clitorises, and all of them couldn’t drive. One day one month later Jack bit the bullet and decided to propose to Molly. He bought an antique ring that was cheap but looked thoughtful. It was the kind of ring you could get in Florence on the bridge for four hundred euros and pretend it came from Paris. He plans a weekend in Saratoga. He has no idea he is not interesting. He has never wanted for women. Molly’s dad has a sailboat they take out on the Cape. At the very least, he will have a summer place to go to all his life. He receives a text the first morning in Saratoga, from Joan.

Hey buddy: book party/clambake out in the Hamptons, couple of directors I can intro. This is a Must come.

Molly was in the shower. They were about to go horseback riding. He wanted to punch something, or fuck a slutty girl. His anger peed out of him in weird ways. He didn’t want to be this greedy about always wanting to be in the right place at the right time. Molly was singing Vampire Weekend in the shower. She had brown hair and makeupless skin. He thought of Joan in a cream satin dress with vermilion lips beckoning to him from a foaming writer’s beach.

Joan was staying in a house in Amagansett with a strawberry patch path to the beach. The bedding in her room was vineyard grape themed. What was awful and what gave the whole house a depressed cast was how many times she had changed shd to should, then finally to must in that text. And then capitalized Must. She thought of grape must, in her room lotioning her legs, praying to the perfect clouds that Jack would come. She wanted his balls inside her. She wanted him more than her whole life.

BE HAPPY IN EVERY MOMENT, said a sign on whitewashed store-bought driftwood in the hallway that connected Joan’s bedroom to the bedroom of the fifty-something corporate realtor who was trying to sleep with her all weekend.

An entire forty percent of him had activated plan B. Plan B was, he hightailed it out of the B and B he got on discount from Jetsetter and texted Molly from the road something panicked about something that happened with a surprise for her that evening. They had been dating for six years and she had seen him bring the special bottle of Barolo with him and she was expecting it, so what would be the big deal if he just made up a story about his buddy who was supposed to bring the newly purchased ring to Saratoga, but then the buddy gets tied up at work. It was the best kind of lie, because she would know for sure she only had to wait one more night for a ring. But then a wave of something he imagined to be selflessness washed over him so he wrote back:

Sorry, kiddo. Out in Saratoga, wrong side of the Manhattan summer tracks. You don’t know how bummed I am. . . .

In her room sadly smelling the Diptyque candle she bought in case he came, Joan went on Facebook, which she’d promised herself she wouldn’t do anymore. She clicked on Molly. She hated when men used ellipses. Why do men use ellipses?

. . . means I don’t give that much of a fuck about you . . .

When someone hasn’t changed a thing on Facebook in several weeks, then all of a sudden there is a new cover photo of a ring on a finger on a candlelit table, someone else might kill herself. That’s something that Facebook can do.

Joan called her therapist on emergency, and she was sitting on the floor of her grape-themed room drinking a glass of red wine in the summer. She told her therapist, I’m on my second glass of wine since I’ve been talking to you. Her therapist said, We should be wrapping up anyway, but Joan looked at the clock, and it was 8:26 and they had four minutes left, and she wanted to kill everybody. She wanted to kill her therapist’s wheaten terrier, who was whining in the background, like he was reminding Joan that other people had amassed a family, while she had eaten at every restaurant rated over a 24 in Zagat.

Molly was twenty-six. It was the perfect age to be engaged for a girl.

Jack, at thirty-two, was the perfect age to settle down. He hadn’t rushed like his friends who pulled the trigger at twenty-five for girls whom they were definitely going to cheat on with women like Joan, who you could tell from their lipstick would give wet, pleading blow jobs. Everything with Molly was great. She didn’t even nag. Actually, Molly’d asked him when they first moved in if he could vacuum the plank floors, but he hadn’t done that yet, so he knew Molly vacuumed, then washed the floors herself. He knew that if her father knew she was cleaning so much he’d be pissed, but he also knew Molly wanted her father to like him, more than she herself needed to like him.

The day of a wedding is always about three people. The groom, the bride, and the person most unrequitedly in love with the groom or the bride.

After fifteen years of not smoking, the day of the wedding Joan starts smoking again. When she was fifteen she started smoking and wearing makeup. At twenty-eight she started removing the makeup, especially from her eyes, with fine linen cloths. At thirty-six she treated each fine linen cloth as a disposable thing, using one for every two days. It made her feel greedy and wealthy and safe. It made her feel old.

Jack is nervous as hell. He is also excited for the attention, even though the wedding party will be small. It is going to be at Vinegar Hill House, a big group dinner after he and Molly sign the papers at City Hall. Molly asked him not to shave because she loves his beard. He thinks of their handwritten vows. He is excited to perform his.

Joan ditches the salt scrub in favor of the eyelash tint. The face is more important than the body if nobody is going to make love to you that night. Without makeup, her face is the color of ricotta. She smokes five cigarettes before nine a.m. and the ricotta turns gray, like it’s been sea-salted. By noon she has had seventeen. She has cigarette number twenty and she thinks maybe she should take the car. She’s wanted to take the car for maybe seven years now. She keeps putting it off. When Joan was twenty, her father told her she could do anything. He told her not to jump into anything. He told her the world would wait for her.

*

Twenty. When Molly was twenty she took a class called Jane Austen and Old Maids. It frankly stuck with her. Today Molly gets ready alone, in the apartment she shares with her husband-to-be. She does her own hair, which is long and brown, and she fixes twigs and berries and marigolds she got from the co-op into a fiery halo at the top. She’s naked. The sun comes through the uncleanable windows and lights the garland and she looks like an angel.

She shimmies the ivory eyelet dress on over her pale body. She catches sight of her full breasts in the ornate antique mirror they bought upstate the weekend of the engagement. Coming down her body a tag inside the dress scratches the meat of her left breast. The tag says, Cornwall 1968. She bought the dress at a thrift store in Saratoga. Everything that weekend was magic.

*

Sixty-eight. Her grandmother and her mother’s two sisters died at sixty-eight of complications from breast cancer. Her mother was diagnosed two years ago, at fifty-eight, so back then Molly thought about a decade a lot. Ten years. Now she thinks that it’s OK that the past two haven’t been perfect. That they have eight left. Her mother is the kind of mother who always had brownies in an oven. Her mother loves her father so much she can’t imagine the two of them disconnected, she can’t imagine her mother in the ground and her father above it.

She puts on cowboy boots, a simple pair of ruddy Fryes that have been to Montana and Wyoming and Colorado inside horse muck and in salmony streams. The dress is tea length and her calves are lovely. The last time she wore the boots was at a horse ranch weekend with her girlfriends, the month before she met Jack. She made love to one of the cowboys with her boots on in a lightly used hay-smelling barn in the moonlight and he came inside her and Jack never has. The cowboy stroked her hair for an hour after they finished. He said, If you ever decide the big city’s not for you, come see me. I’ll be here. He had a silly cowboy name and he wore a bolo tie and her friends made endless fun of her. She never felt safer. Now every time she smells hay she thinks of kindness.

Since Molly was seven, she has measured her care for someone by whether or not she would leave snot on their floor. When she was seven and sleeping at her cousin Julie’s house, Julie had refused to let Molly have a certain stuffed bear to sleep with, even after Molly cried and begged, even after Julie’s mom, who was now dead of breast cancer, had asked Julie to let Molly have the bear, but she didn’t tell her daughter to do it: she only asked, which was how you created monsters.

Molly cried so much that night that her nose filled with gray storm. In the morning she was less sad than bitter. Tears had dried like snail treads down her cheek and her nose was filled with calcified pain. She cleared each nostril with her child finger and dropped the results, like soft hail, one by one on Julie’s bedroom carpet. She left the tissues there, too, hidden under the nightstand.

You could also reverse the test: you could measure how much someone cared for you by whether or not you could imagine them leaving snot on your floor.

Molly walked the three blocks from her apartment to Vinegar Hill House. There was no limo for this bride, no ladies-in-waiting holding her train. She was doing everything herself. When her parents had offered, she’d refused their financial assistance. Her father’s money would make her think less of Jack.

When a moment is upon you, the best you can do for it is to imagine it in the past. Like how a whole weekend with friends will come and go and mostly you’ll be glad when everyone is gone home and later you’ll see a picture of yourselves on a lobster boat in red and blue sweatshirts smiling and blinking against the September suntanless sun and you’ll think, I must have been happier that day than I thought I was.

The restaurant is set for the wedding. The mason jars for cocktails, the burlap runners, the long wooden tables, and the bar mop napkins. The wedges of thick toast are out already on rough cutting boards awaiting their marriage to cheese. The votives in Ball jars, the kombucha on tap. The ceremony will happen on the terrace, the officiant will be some large-gutted Pakistani friend of the groom’s, and it will be shorter than the life-span of a piece of gum.

Her vows are simple and unspecific. She had always thought her wedding vows with the man of her dreams would be specific, about things he did with his cereal, flowers he stole from the grates of Park Slope, picayune habits he had that were annoying, his smelly obsession with roll mops. Jack doesn’t vacuum. She was going to work that into her vows and then she felt tired.

For the past two months Molly has been finding tissues. He doesn’t vacuum, so she finds the crumpled tissues, like lowbrow snowflakes, in the corners behind their bed, on his side, and also on hers. It is not mere laziness. It is the triumph of his indolence over his love for her, and it is dishonest. She has her dishonesties, too. She asked Jack not to shave because underneath the beard he is gaunt and sallow and looks like the unemployable actor her father promised he would become.

Twenty-six is Molly’s perfect age. She thinks of the six years she has spent with Jack, the eight years she imagines she has left with her mother. She thinks of the impending six-minute ceremony, and the forty-three minutes the cowboy fucked her in the hay during which time she came and then came again against the milk-bearded mooing of the cows outside and the whistle of the humble Colorado wind. The ecstasy of grass, the violence of milk. Staring at the wedding bounty before her, feeling the weight of the crown of flowers in her hair, she knows there are hundreds, thousands, who will be jealous, but she doesn’t know them by name. She whispers the name of the cowboy to the unlit candles like a church girl, to the naked bread and the tiny daisies in tiny glass jars. She incants the name, and the name itself, like the memory of a moment before it becomes a legend, frees her enough to think the thing she has been thinking for ten thousand seconds, for one hundred billion years, the thing we all think when we finally get what we want. The right way to do something might be the wrong way in the end. Fortunately or unfortunately, both ways lead to Rome.

Joan is on her way, in the car. On her way she receives a text from Jack.

There’s a hidden message to you in my speech thing today. Shhh. . . .

Jack is on his way, in a cab. He sends the text to Joan. Not having been employed for a couple of years, he feels good rattling off a text that he knows will go a long way, for his career. It feels like an Excel spreadsheet. Also, how he thought to change shout-out to hidden message, because it sounded warmer. Finally, on the way to his wedding, he marvels at how easy it is, with women. If only they knew how little time we spend thinking of them, and if only they knew how much we know about how much they think about us. The freaking man-hours a woman puts into men! To looking good for men. The brow tints and whatever. And at the end of the day, you can be twenty-six and it doesn’t matter. There’s someone out there who’s gonna be eighteen, with a smaller vagina. Jack is so happy he isn’t a woman, even if he is an actor.

The motor is on in the Volvo in Manhattan and there’s a wedding in Brooklyn and Joan reads the ellipsis, finally, for what it is. She reads it all the way through to the end.

At the restaurant with a few Mexican waiters watching her with genuine care and admiration, Molly calls the cowboy’s name like he is in the room and like she did in the hay that day and she says it to the wildflower bouquet housed inside the McCann’s Irish Oatmeal tin on the wedding cake table. Like Snow White speaking to the forest creatures she leans down and says his name to the ironic bird-and-bee salt-and-pepper shakers, and none of them answer, or come to life. Which makes her feel bummed, but she regroups, because there is a silver lining, like the one in the oatmeal tin that cuts your finger if you aren’t careful.

In the distance she sees Jack, though he doesn’t see her. She sees him come into the place and check his hair and smooth his beard in his reflection on a dirty window. It’s time to do this. Everything is time. You commit yourself to a course in life, to a course of treatment, but nothing lasts forever, not the good or the bad. Molly, feeling the most beautiful she will ever feel, adjusts the marigolds in her hair, and thinks, Forty-two. If she dies at sixty-eight, like all the breast-charred women before her, she’ll have just forty-two years left.

__________________________________

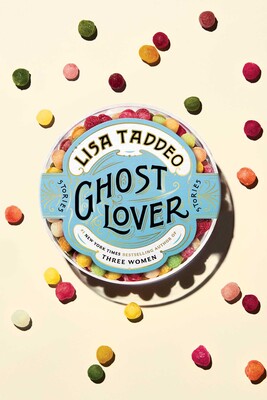

Excerpted from Ghost Lover by Lisa Taddeo. Copyright © by Lisa Taddeo. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Avid Reader Press.