I had something of a mental breakdown in the hours before getting my first tattoo. According to everything I learned growing up, nice Jewish girls aren’t supposed to get them. And according to everything I learned about women and aging, we’re not supposed to get inked when we’re much too old to be considered “girls,” or even young women.

These “rules” overtook my mind October 1, 2012, the day before my 47th birthday, as I prepared to walk into East Side Ink on Avenue B in Manhattan—but I didn’t let them stop me from sitting down in the chair, extending my arm, and getting my first of what has now grown in number, at this writing, to three tattoos.

I almost let them stop me. Those deeply ingrained dictates, plus my aversion to pain, nearly put the kibosh on my plan. There was also my concern for how my parents might feel.

*

That fall afternoon in 2012, my husband, Brian, sat with me on the lawn in Tompkins Square Park and listened to me spin out, tearfully debating with myself whether I was prepared to permanently alter my right forearm. Deep down I knew I’d go through with the appointment that I’d set up weeks in advance. But as with many experiences I didn’t feel I had permission to try, I seemed to believe I’d only be justified in enjoying it if I first put myself through a fair amount of suffering.

Mind you, I was carrying on about this and crying out loud. In the middle of a public park. God bless Brian. As we sat on the lawn, he entertained all my rhetorical questions from every side of the argument. Brian is kind and incredibly patient with me when I get caught up in this kind of endless, circuitous back-and-forth of should-I-shouldn’t-I?.

I wasn’t just debating with myself, but with my parents and other relatives, dead and alive, too—all in my head. This entailed a fair amount of projection, but as an empath, I was already a pro at taking on other people’s emotions and points of view, or what I imagined them to be. One therapist described me as “a radio receiver for other people’s feelings,” with a woeful inability to determine whose emotions I was experiencing when other people’s wants and needs got thrown into the mix.

My parents are pre-boomer Jews. In the hours before my tattoo appointment, I couldn’t stop putting myself in their (theoretical) shoes. (You might consider playing “Sunrise, Sunset” from Fiddler on the Roof on the turntable in your mind through this part of the story.)

I’m not a parent. I do not have first-hand knowledge of what it’s like to have your baby, your first baby, alter one of her limbs irreversibly with a variety of body art your age group still associates with tough guys and outlaws, and which is forbidden by your religion. But my non-mom status didn’t deter me from the mental gymnastics involved in taking on my parents’ presumed viewpoints.

Back and forth I went—first imagining my parents feeling wounded, upset and angry with me, then countering those thoughts by reminding myself I was 47.(It’s true, by the way—the Torah forbids tattoos. In Leviticus 19:28 it is written: “You shall not make gashes in your flesh for the dead, or incise any marks on yourselves.” What’s not true is the notion that you can’t be buried in a Jewish cemetery with them. Misconception or not, it happens to be the premise of “The Special Section,” my all-time favorite episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm [Season 3, Episode 6]: Larry learns that his newly deceased mother can’t be buried in a regular plot in the Jewish cemetery because she had a tattoo on her butt.)

I made a major production out of my internal debate. Back and forth I went—first imagining my parents feeling wounded, upset and angry with me, then countering those thoughts by reminding myself I was 47, very much past an age at which I’d need their permission or approval, or to consider anyone else’s feelings about what I do with my own body.

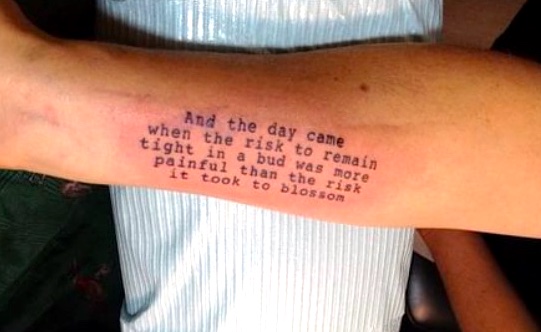

Ironically, this tendency to be overly concerned with other people’s opinions and feelings—allowing them to keep me from being fully myself—was part of the point in a) getting a tattoo in the first place, and b) getting the specific one I’d chosen, the following quotation, in the American Typewriter font: “And the day came when the risk to remain tight in a bud was more painful than the risk it took to blossom.”

I kept perseverating until five minutes before my appointment. I needed to pull myself together, not just for me, but for my “tattooula,” as well.

*

My friend Emily—a much-tattooed writer I admire who is sixteen years younger than me—had offered to come and support me through the experience, as she’d done with other friends. She joked that she was a “tattooula,” like a doula for people getting tattoos for the first time. She began her work the night before, talking me down from my fears over dinner and karaoke in Chinatown. The next afternoon she was waiting for me in front of East Side Ink armed with a box of gluten-free cookies. “You want to make sure you have energy and that you keep your blood sugar balanced,” she said.

She had already assured me several times that the application of the tattoo wouldn’t hurt, at least not too badly. “Do you swear?” I’d asked each time. I had almost been scared off entirely by Brian’s story of getting tattooed on his left shoulder blade in his thirties—a hippie tattoo, “Mother Earth,” in the form of a pregnant tree. It had hurt so much, he wrote a song about the pain. But Emily insisted the degree of pain was different depending on the part of your body, and the inside of the forearm was one of the areas where it tended to hurt the least.

Emily and Brian sat on either side of me as the tattoo artist, Minka, applied a “transfer,” a temporary tattoo of the quotation, to my forearm, and then began tracing it with her pen. One letter at a time, I was surprised by how little it hurt. Minka had suggested it would have the sensation of a series of mosquito bites, but it was even less annoying than that.

Maybe it was the attendant endorphin rush, but I found the experience bordering on enjoyable. (The night before, Emily had said getting tattoos was addictive, and I’d insisted I’d be getting only this one tattoo for the entirety of my life. Well, famous last words.) As Minka applied ink to my skin with her buzzing pen, I began to understand what Emily had meant. I felt perfectly elated.

In a patriarchal capitalist culture, where value is based on austerity and scarcity, it can be hard to feel secure enough to just let our guards down and be generous with one another.When it was over, Minka applied Aquaphor to my arm and covered the tattoo with plastic wrap. It was oozing ink, which she said was normal. I looked down at the words on my arm, and felt a rush of satisfaction. I had not one regret. All my fears, all the drama from before vanished. I wasn’t ready to tell my family about it quite yet. But it was enough for the moment to enjoy it as my little secret.

*

I awoke the next morning in the East Village Airbnb where we’d stayed, and admired my arm. I was still elated, and self-satisfied for having gone through with my appointment.

The apartment we were staying in was directly across from the spot on East 7th Street between Avenues C and D, where Brian and I had met nine years prior. Meeting Brian had been both a function of, and a furthering of, becoming truer to myself in relationships. Before meeting him, my dating pattern had been to tune my antenna to the most ambivalent, or difficult, or damaged, or self-absorbed man in the room—or some cursed combination of those qualities—and then twist myself into a pretzel to become whatever version of me I thought might earn and keep that man’s hard won attention. That had often meant keeping my true thoughts to myself, and making myself small and needless, so that I didn’t ruffle feathers, or reveal parts of myself that might offend, or scare a man away.

In the years leading up to meeting Brian, I had been in treatment with a male therapist I often referred to as The Swashbuckling Shrink, who was helping me break that cycle and find satisfaction in every aspect of my life by getting comfortable being myself, and expressing myself. Brian had also been “working on himself” in therapy. He and I have often said that if we’d met even just a couple of weeks before we did, in the fall of 2003, neither one of us would have been quite ready for the other.

We each had final hurdles to get over before we were ready to “tolerate” a relationship with a kind, available person, someone who knew that for a relationship to be mutually satisfying, each person had to consistently consider the other’s needs. It seemed like such a simple, intuitive concept, but in a patriarchal capitalist culture, where value is based on austerity and scarcity and we’ve all been taught to be withholding, accordingly, it can be hard to feel secure enough to just let our guards down and be generous with one another.

The next hurdle toward becoming more fully myself was finding the courage to put myself out there more as a writer. I’d been hiding myself for years, chickening out when opportunities to publish personal essays came my way. For years—decades, even—I felt as if I were standing on a ledge, but too scared to jump. It was as if I were waiting for some “right time” that never arrived. In the meantime, I floated aimlessly from one writing or writing-adjacent gig to another, including ghostwriting assignments. (Could there be a better metaphor for hiding as a writer?)

After I had the tattoo inked on my forearm, I began to feel bad that I hadn’t included her name. It seemed appropriate to attribute it.Then, in 2012, after a ghostwriting assignment with a particularly difficult author had gone south, I felt desperate to commit to my own work. That was what made me choose the quotation I did for my tattoo. Every single word of it rang true: And the day came when the risk to remain tight in a bud was more painful than the risk it took to blossom.

I’d come across that quotation so many times in my life—on mugs and candles and journals and yoga mats. There was a corniness to it and its proliferation. It was also phrased awkwardly. Still, those words had always spoken to me. I had often felt exactly what they meant to convey—the sense of reaching a point where staying stuck, staying small so you don’t offend anyone, becomes more impossible than finally speaking out. Now I felt it more strongly than ever.

I assumed they were the words of Anais Nin, because I’d frequently seen the quotation attributed to her. After I had the tattoo inked on my forearm, I began to feel bad that I hadn’t included her name. It seemed appropriate to attribute it.

It turned out to be a good thing I didn’t add attribution.

*

In March of 2017, an upstate arts magazine assigned me a profile of legendary magazine editor Joan Juliet Buck, who’d just published her memoir, The Price of Illusion. In the course of the interview, Joan noticed my tattoo. She asked to read it, and I held up my arm before her eyes. When she was done, she looked up and said, “I knew Anais Nin.” Then she asked, “Which of her books is that quotation from?”

Uhhh…

I had no idea. I felt like such an idiot. I’d read a little bit of Nin over the years, but I wasn’t any kind of avid fan. I’d chosen the quotation for my tattoo because the sentiment resonated so strongly, not because I was any kind of Nin aficionado.

“I’m embarrassed to say I’m not sure,” I admitted to Joan. And then we moved on to the next part of the interview.

The first thing I did when I got home was google the quotation, to see if I could determine which book it came from. That’s when I stumbled upon a blog post by the Anais Nin Foundation explaining that the quote hadn’t come from Nin at all.

Six months prior, in the fall of 2016, a woman named Elizabeth Appell spoke out publicly about her poem, “Risk,” being misattributed. In the 1970s, at the time she wrote it, she was known as “Lacey Bennett,” and she was a publicist for an adult education college in California. She’d included that portion of “Risk” in a press release encouraging people to go back to school. She reached out to the Anais Nin Foundation, explaining the situation, sharing with them a copy of the original press release.

I got in touch with Appell to ask her about the story behind the quote that was now emblazoned on my arm, for life.

“I was Public Relations Director for a university that operated just for adults,” Appell explained. “I put out a quarterly bulletin about the school, and classes we had available. I always tried to find interesting themes. I remember the moment I wrote it. I was on the telephone talking to somebody and I said, ‘Excuse me, I have an idea, hold on.’ I sat down and wrote those lines, and then I wrote another four lines. I have no idea what happened to the other four lines, they’re gone. I just wrote them down. Then I took them to the fellow who was the Director of Development. I said, ‘This might be a good kind of inspiring thought for the next bulletin, and we could create an image of roses opening around it to convey the idea that adults are going back to school and opening their lives to all new things.’ He liked it very much. We put it out. It went out in Contra Costa County, here on the west coast. A lot of people saw it.”

There have been so many times and places in my life when I was pretending to be someone else, trying too hard to fit in, and getting a tattoo later in life could have easily been one of them.Appell hadn’t thought to give herself credit for the poem when she put it on the press release. “I didn’t put my name on it,” she recalled. “I didn’t even think about it. Then I started seeing it in weaving shows—people would weave it into tapestry. Then I went to a calligraphy show and saw it. Then, in 1979, I was in a little card store, and I saw it attributed to Anais Nin. I bought the card and I wrote to the company. I said, ‘I’m not going to sue or anything, but this is not Anais Nin’s; I wrote this.’ They wouldn’t even speak to me, because I think they were afraid.”

She gave up the fight—until a few years ago, when the quotation was absolutely everywhere, including her own small corner of the literary world.

“I was giving a reading of my work, and a woman who had read just before me opened her reading with that poem and attributed it to Anais Nin,” Appell recalled. “My husband was there and he raised his hand. He said, ‘I just want you all to know that that poem was not by Anais Nin, it’s Elizabeth’s poem,’ he said, ‘and I can prove it.’”

Her husband speaking up made Appell uncomfortable. “At that point, not a lot of people believed me,” she said. “I was kind of upset with him. I said, ‘Don’t do that. Who cares who wrote it?’ He said, ‘No, you wrote it. Lots of people like it, they should know you wrote it.’” Wow, I thought: Even the woman who had written those very words was susceptible to remaining tight in a bud!

In the end, though, Appell was glad her husband spoke up. It inspired her to get a hold of the Anais Nin foundation. “I told them the whole thing about how I wrote it, when I wrote it. The fellow who was the Director of Development for the university wrote them a letter saying, ‘Yes, I corroborate this, she did write it.’ Finally, they believed me, and then they put a notice out.”

*

Before getting tattooed, I’d already done something like it once before—altered my body in a way that was more in keeping with people younger than me. At 33 I got a navel ring. It made me feel sexy and bold, and it also helped camouflage a scar I’d long hated, a keloidal slash across the middle of my belly button, the result of laparoscopic surgery I’d undergone at 18, to diagnose endometriosis. (In getting the incision for my navel ring, I risked developing another keloid—I’ve had three keloids surgically removed in the course of my life.)

I couldn’t wait to show the simple stainless steel hoop with a little, round, jade stone as its closure to Tim, the guy I was seeing at the time. I didn’t do it to please him, but I thought that might be an advantageous by-product. I imagined he’d find me irresistible. When I lifted my shirt to show him, he gave it one look, then lifted his eyes to mine. “How antithetical,” he said, in a sarcastic tone. “Good for you.” It did not have the desired effect.

But it didn’t matter what Tim thought. Getting the navel ring made me feel in control of my body, which I’d felt out of control of since it began growing curves during puberty, and then developed an eating disorder, and later endometriosis. The tattoo had a similarly salutary effect. I felt in control of my body—in charge of it—and empowered.

There have been so many times and places in my life when I was pretending to be someone else, trying too hard to fit in, and getting a tattoo later in life could have easily been one of them. But it wasn’t. With my new ink on my arm, I felt more like myself, more committed to being who I was, and more committed to my writing.

Incidentally, I took my navel ring out after a few years. A psychic I was ghostwriting a book for told me it was messing with my third chakra, the one responsible for my self-esteem. So I took it out. I wish now that I hadn’t. (Of course, after removing it, I developed a tiny keloid there.)

*

Even though I’d had such a positive experience with my first tattoo, it hadn’t initially occurred to me to get more of them. I figured I was done after just the one. But then, as my 50th birthday rolled around in 2015, I felt the urge to get another. I wanted to mark my half-century, but there was more to it. In the three years since I got the quotation on my arm, I’d taken some risks with my writing. But I was still holding myself back. I wanted to embolden myself to take things to a new level.

A friend had gotten a tattoo of a flock of birds flying across her shoulder, and just seeing it on her gave me feelings of flight—of freedom and liberation. I wanted to get something on my own body that would inspire similar feelings. Looking online at images of birds led me to images of them seated on cherry blossom branches. I’ve always loved cherry blossoms, and have a weeping cherry tree in my front yard.

It gave me a thrill, and it gave me the sense of self-determination and self-assurance that I needed.Next I started going around to tattoo parlors in Kingston, where I live, with printouts of cherry blossoms I’d found online. Most artists said they were too delicate, and passed. Then I found Pat Sinatra, an older artist who was getting ready to retire in a few years. She said she could do it, and so, once again, the day before my birthday, I sat in a chair and had ink applied, this time to my upper left arm.

Shockingly, it would not occur to me that there was a correlation between my text tattoo about blossoming and my new tattoo with blossoms until I woke the next morning and took stock of both. Duh.

Okay, now I’m really done, I thought. Apparently I wasn’t.

*

There are few things I dread writing more than book proposals. What could be more anxiety-provoking than writing what is essentially a lengthy book report on something you haven’t written yet?

In 2019, as I was slogging through a proposal for this very memoir-in-confessions, I made a bargain with myself: get yourself a book deal, and you can mark the occasion with a new tattoo.

In June of 2020, during the coronavirus pandemic, I got the good news: Heliotrope wanted to publish me. I was thrilled—and I was itching to celebrate by getting inked again. But at that time, tattoo parlors in New York were still closed, due to Covid-19 restrictions.

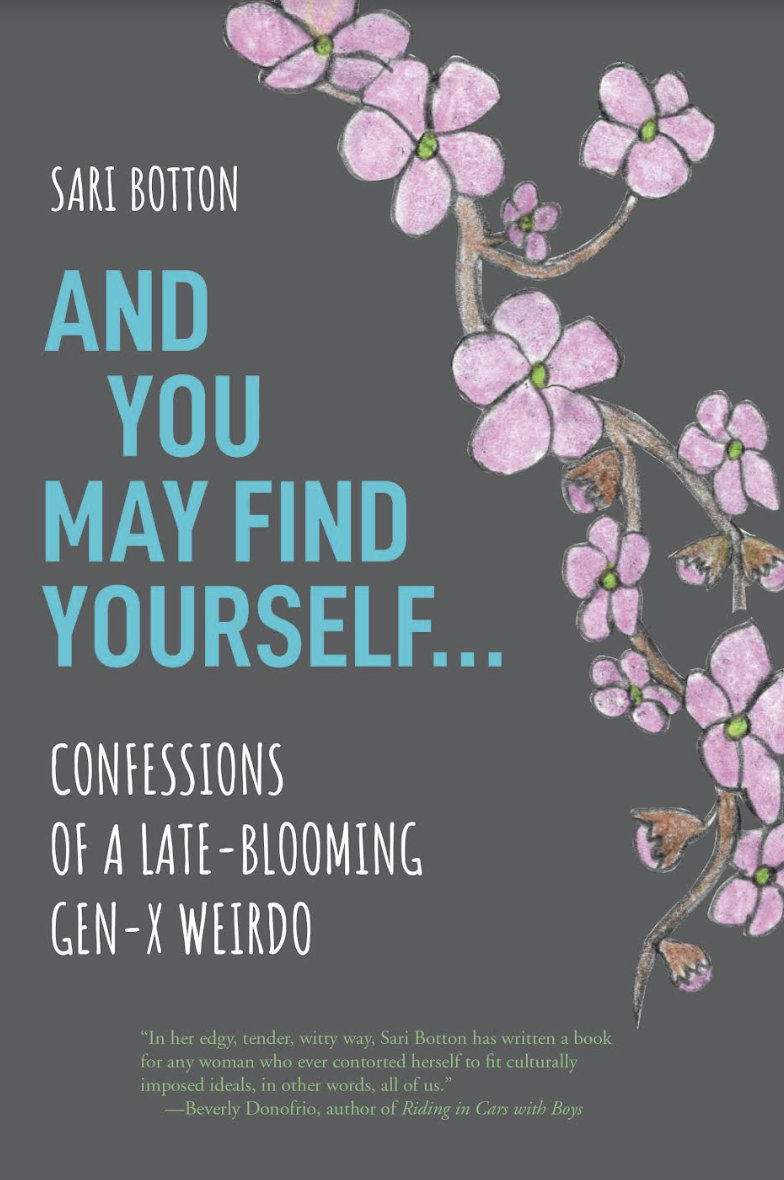

It was just another of so many letdowns in a hellish year. I yearned for the ritual of getting a tattoo, and I had the perfect design in mind: a rudimentary typewriter that I’ve been doodling in crayon for years. I’ve used the image before as a logo—for a writers’ group I ran in the early aughts; on the first iteration of my website; on stationery. Now I wanted to get it imprinted on my left forearm to commemorate signing, at the ripe old age of 55, the first contract for a book filled exclusively with my own writing (I’d published anthologies before, but they were mostly filled with essays by others), and to help me commit to getting it done.

I’d already learned that there’s something galvanizing about having images and words permanently scrawled into your flesh. It sends your mind the message, “I mean business.” After signing my book contract, I was ready to send my brain that message with the typewriter tattoo. New York tattoo parlors were allowed to reopen in July. But the continued spread of the virus gave me pause.

I got to work on this book, but struggled. Once again, I’d taken on too much editing of other people’s stories to write my own. Finally, in November, 2020, I cleared my decks to commit more deeply to my writing. The urge to visit a tattoo parlor grew stronger.

One afternoon, on a whim, I called Metamorphosis Tattoos, around the corner from my house in Kingston. Initially, the woman who answered said there were no open appointments until mid-January, but then she paused. “Actually, we have a cancellation this afternoon,” she said. “How soon can you come in?” I asked about their adherence to Covid-19 protocols, and the woman assured me that they took the greatest precautions. Fifteen minutes later I was sitting in Tania the tattoo artist’s chair.

Tania’s tattoo pen buzzing away, I grew elated. It gave me a thrill, and it gave me the sense of self-determination and self-assurance that I needed.

After that day, I became emboldened, writing more committedly and bravely than ever before. Yes, it was still hard staying focused when there’d been so much illness and fear and bad news—including three Covid deaths within my extended family. But I made progress every day. When I wasn’t writing, I couldn’t stop staring at my lovely new ink.

___________________________

This essay appears as “The Girl With the Nerd Tattoos” in Sari Botton’s new memoir, And You May Find Yourself.