“Yes!” I squeal. “Exactly! Bukowski. That’s good.” We are milling under a weak spring sun outside a breakfast diner, postfeast. I’ve been enthralling Luca by telling her something weird about Tinder. All married friends like a good Tinder story. They find it hilarious and thrilling, the way single friends find the same story humiliating and terrible. On Calgary Tinder—amidst the rifle-shining and gleaming scales of fresh-caught fish, the deer carcasses and camouflage, the “partners in crime” flashing peace signs while proudly “living life to the fullest”—I’ve noticed an odd and surprisingly literary phenomenon. Nearly every second male profile lists Kurt Vonnegut as its favorite writer. I say odd, but I’m not yet sure.

I myself have never read any Vonnegut. In fact, the only person I can recall loving him was Trevor S. from grade twelve English, who had a burning passion for Slaughterhouse-Five, spiky blue hair, and a weight problem like my own. We were hardly friends, though I knew no one else as frenzied as I was by books. Perhaps this is why I remember that he loved Slaughterhouse-Five—though it could be the title itself, which is magnificent and lodges in the mind. I don’t recall much else about Trevor, except that he wore the same massive nubby black sweatshirt every day, and I imagined he had a crush on me. Do I need to say he was not popular? Well, neither was I. But in terms of tiers, I fancied mine one above his and thus didn’t wonder much about him.

So. Has Luca read Kurt? Does she like him? Would she say he’s most suited to chubby blue-haired high school boys? Is he worth the investment?

Luca thinks for a moment. Her face loosens from the Bukowski grimace. A flash of mirrored sunlight flickers over her cheekbones. So there is truth, I think with an admiration surprisingly untouched by envy, to the phrase “pregnant glow.”

She opens her mouth to say something undoubtedly clever, but before she can get any word out, a man with a pompadour, leather jacket, and aviators thrusts into our conversation, scarf flying as though he’s been blown in by a wind. Heretofore, he’d been leaning against a bicycle rack near the diner door, presumably waiting for his name to be called.

“Slaughterhouse-Five,” he barks.

“Pardon me?” I say, taking a step backward.

Luca has doubled over in laughter.

“Slaughterhouse-Five,” he says with the authority of the pilot he appears to be impersonating, “is the only one you need to read. If you’ve read that one, you’ve read them all.”

He looks like he’s about to offer more advice, but I grip Luca by the sleeve to tug her away.

“Well,” says Luca, still laughing, “that is the only one I’ve read.”

*

Of course, not everyone lists a favorite author on a dating app. But in the words of a meme attributed to John Waters, “If you go home with somebody and they don’t have books, don’t fuck them.” My Tinder profile is snappy and announces its literary prowess. I list my favorite authors in order—Elizabeth Bishop, Anne Carson, Maggie Nelson. Hint to the reader: if any date opened conversation by asking my thoughts on “The Glass Essay,” I’d be undressed within the hour. This has never once happened. Not even on a date with a self-published author who promisingly announced his favorite book as Toni Morrison’s Beloved. I germanely asked if he’d ever seen a ghost (my first-date banter is exceptional). He sneered! “You don’t believe in ghosts, do you?” he said. This after it had been made clear, by my mention of the early-aughts afternoon television show Crossing Over with John Edward, that I do and fervently. The self-published author made a horsey sound of displeasure over what he called an evolutionary failure. By that he meant me.

On Calgary Tinder I’ve noticed an odd and surprisingly literary phenomenon. Nearly every second male profile lists Kurt Vonnegut as its favorite writer. I say odd, but I’m not yet sure.“I thought,” he tsked, “that humans had evolved past the need for banal superstitions.”

The pervading love of Vonnegut seems intellectually interesting in a way that almost nothing about a dating app is intellectually interesting. So I have decided to read him. If nothing else, it will make for more unforgettable table-side banter. I will read Vonnegut and forthwith date only those who call him their favorite writer. A timely and novel literary experiment. Likely a divining rod for true love.

*

The first thing you will notice about Vonnegut is that he loves a simple, muscular sentence. Both prose and plot line are as easy to follow as Simon Says, which is perhaps why he is beloved by high school boys. But do not mistake syntactic simplicity for undeveloped craft. The well-chosen verb, the surprising image—both blossom in Vonnegut. Take, for instance, this wet dream of a sentence from Cat’s Cradle: “He exhaled fumes of model airplane cement between lips glistening with albatross fat.” Stop and read it aloud. Such crisp prose! Such imagination! Or consider the snips of dialogue uttered by one of Vonnegut’s more rounded women characters, Bluebeard’s termagant Circe Berman. Said to narrator Rabo Karabekian: “You hate facts like poison.” So sharp! Said of the self-important writer Paul Slazinger: “the spit-filled penny whistle of American literature.” What a zing!

In keeping with this slick style, Vonnegut more than once pronounces hatred for the semicolon. Reading his 2005 collection of essays, A Man Without a Country, you might cringe over this strange aphorism: “Here is a lesson in creative writing. First rule: Do not use semicolons. They are transvestite hermaphrodites representing absolutely nothing.” (Indeed, the “hermaphrodite” is a common trope for Vonnegut. Bluebeard’s Mussolini-loving Dan Gregory calls Joan of Arc one after Rabo offers her as an example of a woman who has excelled in a field besides domesticity. Rabo can’t think of any others.) You would likewise be hard-pressed to locate more than a handful of compound-complex sentences in any Vonnegut book. The man barely has use for the comma. He does, however, have a great penchant for italics.

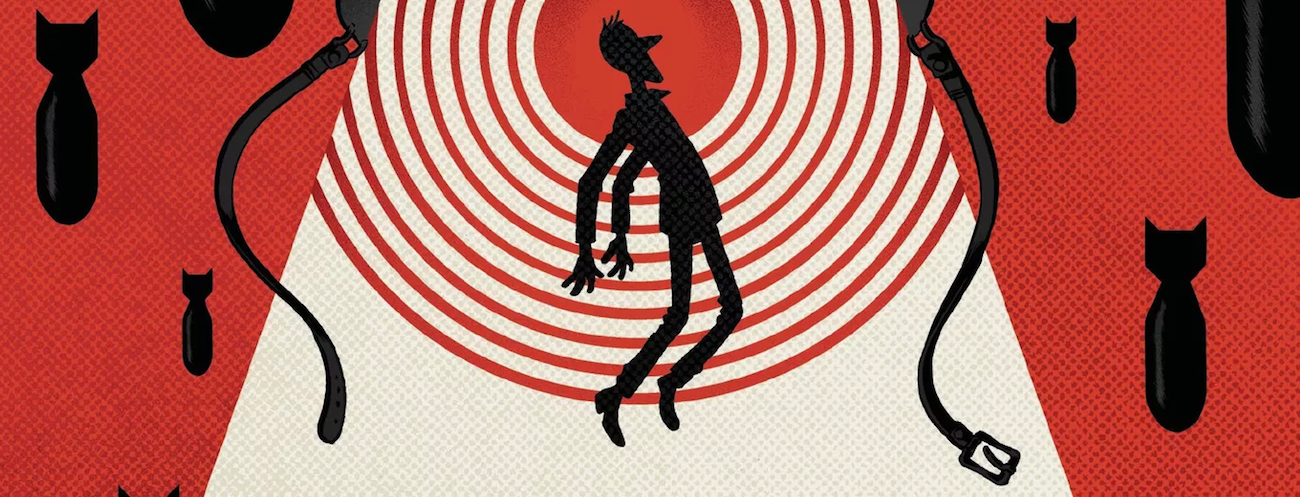

It might be easy to cast Vonnegut as a purveyor of boyish machismo. Chapters are peppered with his hand-lettered bathroom-graffiti-like slogans and cartoonish drawings, such as the asterisk-esque asshole that appears in the prologue of Breakfast of Champions. Vonnegut’s voice is irreverent, antiauthoritarian, the same spirit that animates teenagers immemorial. His mode is satirical, and he possesses a dry wit that, one might argue, rather mercifully sandbags the current deluge of outrage rising all around us. Ours has burgeoned to a self-serious climate where it feels almost impossible—and always crude—to make a joke of any sort (more on this later).

Despite the joys of his irreverence, however, it is all too easy to sink in the morass of sexism, if not outright misogyny, muddying the plots of Vonnegut’s novels. The steady stream of male veteran narrators who lust after and often eventually bed a much younger woman—Cat’s Cradle’s eighteen-year-old Mona Monzano, for example, a denizen of the fictional Caribbean island San Lorenzo, whom the twice-divorced narrator calls a “sublime mongrel Madonna.”

Vonnegut’s women characters are often so stock and paper-thin you can’t help but feel a fresh tide of anger when encountering them. This is particularly so in Slaughterhouse-Five. Billy Pilgrim’s mother (whom Billy naturally dislikes) is described as a “standard-issue, brown-haired, white woman with a high-school education.” Billy’s wife, “ugly Valencia,” is rich and fat and perpetually eating candy bars. Billy’s proposal of marriage to Valencia is thought to be “one of the symptoms of his disease.” She dies of overexcitement and poor driving. The pornographic film star Montana Wildhack, a very young and buxom creature entrapped with Billy in an extraterrestrial Tralfamadorian zoo, raises Billy’s child while Billy absents himself to time travel at will. Vonnegut illustrates Montana’s breasts with a crude drawing that features, in between mosquito-coil nipples, a locket containing the lines of the Serenity Prayer—an indication of his twin obsessions: sex with young women and free will. In the prologue, where the Vonnegut-like narrator explains the decades-long gestation of Slaughterhouse-Five, we get ideas such as this on a war buddy’s wife: “Mary O’Hare is a trained nurse, which is a lovely thing for a woman to be.” We see reporters who took the jobs of men during World War II called “beastly girls.” To be fair, Vonnegut, a true misanthrope, seems to dislike men as much as he dislikes women. Or at least the vileness of his male characters suggests this is so.

Possibly the strongest argument for women is made in Bluebeard. As the title suggests, and as all Vonnegut books do, Bluebeard peers behind the doors hiding the bone records of villainy. In Vonnegut’s analog, Bluebeard’s forbidden room becomes veteran Rabo Karabekian’s locked barn. Instead of murdered wives, the barn contains an enormous realist mural depicting World War II atrocities. The mural is titled Now It’s the Women’s Turn. Reading Bluebeard made me think a bit differently, kindlier, about Vonnegut, though it seems inescapably obvious that his prose is of a staunchly different generation. A sort of “dad joke” writer, who frequently uses words from the fatherly lexicon—snooze, old fart. A writer whose aphorisms read like this: “We are here on Earth to fart around. Don’t let anybody tell you any different.” A writer who pens a wisecrack thus: “My wife is by far the oldest person I ever slept with.” I can easily imagine my own father making such quips. And I’m not sure any of this bodes well for my latest man-catching stratagem.

It seems, too, that the world agrees with the man in the aviators. Slaughterhouse-Five is everywhere considered Vonnegut’s masterpiece. No one I ask can name another of his books, not even Breakfast of Champions, made into a 1999 feature film starring Bruce Willis. “There are novels so potent,” writes James Parker of the Atlantic, “and so perfected in their singularity, that they have the unexpected side effect of permanently knocking out the novelist: Nothing produced afterward comes close.” Parker is waxing rhapsodic about Slaughterhouse’s continued relevance on its fiftieth anniversary in March of 2019. And I must say, at times I too find Slaughterhouse strikingly prescient, at least in its cynicism and apocalyptic visions. Visions induced, like our own, by atomic weaponry and fossil fuels. But even so, even so. Why is the book so popular among the twenty-five-to forty-five-year-old males of my Tinder filter? There are many counterculture writers, writers who celebrate machismo, antiwar and pacifist writers, funny and satirical writers. Why Vonnegut?

*

“So, why Vonnegut?”

I am at an Original Joe’s, where Brad, the first of my Vonnegut dates, suggested we meet. I was initially put off by the Original Joe’s suggestion. If you’ve not had the pleasure, think chain restaurant and let the name guide your imagination. But things are looking up. It turns out they have a taco night.

On Tinder, Brad’s profile consists of glamour shots and a few requisite action scenes that look to be professionally done—in uniform with a stick on the ice, muscles bulging up a climbing wall. In the few sentences that make for getting to know someone on Tinder, he has written a fairly creepy line: “Let’s be perfect, together, Forever.” Reading this, I was both immediately suspicious and electrified.

Brad shrugs. “I like science fiction,” he says dully. “You know, before I went to medical school, I worked for NASA.”

I spill ground beef into my lap. Brad largely ignores my Vonnegut question so he can continue to talk about his work. Abruptly, he sets down his fork. Brad has a hobby. He’s already told me. The hobby is an endless search for the perfect fork. The perfection has to do with the shape of its tines. So Brad sets down his subpar-tined fork, wipes his puckered pink lips with a napkin, and retrieves his wallet. I admit I am startled by this swift turn of affairs. He removes a five-dollar bill, smooths it with a snap, and lays it on the table. Five dollars, I’m about to inform him, will be a tad shy of the bill that has not yet arrived because I’ve not come close to finishing my taco. But no.

It seems inescapably obvious that Vonnegut’s prose is of a staunchly different generation. A sort of “dad joke” writer, who frequently uses words from the fatherly lexicon—snooze, old fart.“I used to be an engineer,” he says, tapping the top of the bill.

Lettuce hangs from my mouth.

“I helped design the Canadarm.”

I, naturally, have never heard of the Canadarm. It takes a minute before I realize it is featured on our currency. When I brag about this to my friend Eliot later, he scoffs. “What is he, like, seventy?”

“A doctor and an engineer?” I say around the lettuce.

“Yup.” He folds away his wallet.

I’m gulping wine while Brad tries to catch my gaze over the orange flicker of the fake tea light.

“Neither of us,” he announces, “has any time to waste. So let’s not beat around the bush.” Brad has blinding, denture-like teeth. He is wearing a suit jacket. I am wearing purple lipstick and a halter top.

My lips curl in a lewd smile. “That’s a funny phrase, if you think about it. The other day, a friend told me a story about how he was facilitating some government training session and inadvertently said ‘bent over a barrel.’ He’s worried he might be fired!”

“I have five questions,” says Brad.

“Oh!” I think Brad is proposing a game, or that we are meant to be having a nice time.

One: Have you ever been married?

Two: Do you have any children?

Three: Have you ever been arrested or convicted of a crime?

Four: Do you have any addictions?

He wags a finger at me. “And that includes smoking.”

“Five,” he concludes: “Is there anything you want to tell me before this goes any further?”

I am so flabbergasted I actually respond to this blaze of rifle fire. Brad, blowing on the barrel and holstering his gun, informs me that he approves. I do not have time to wonder whether equating childbearing with crime is appalling or pleasing.

“Now,” he says, “I’m sure you’re wondering the same about me.”

“No, actually. I was wondering what you liked about Kurt Vonnegu—”

That wagging finger again. “I’ll play fair.” He steadies his gaze and without pause shoots off his five-point response.

“And five,” he says, out of breath and winking. “I’ve already confessed my fork fetish.”

“Five, five,” I am thinking. “Like, as in Slaughterhouse?”

“You’re sure you don’t smoke?” he asks as we move through the door and part ways.

Since Brad never told me, I’m left to my own devices to guess what he likes about Vonnegut. Perhaps, I think with self-satisfied glee, he enjoys how the women in Slaughterhouse are mere props. Perhaps he cackles over the only woman mentioned in the Dresden plot, the one in a photograph attempting to copulate with a horse—a slice of historical pornography carried by the masochistic soldier Roland Weary. Perhaps, due to his affiliation with NASA and the robotics industry, Brad simply admires the science-fictional elements—Vonnegut’s Tralfamadorians and their fourth-dimensional concept of time, where everything that has ever happened and will ever happen occurs simultaneously and where unpleasant states, such as death, are just one moment of many that can be visited at will. But even the Tralfamadorians are implicated in the seedy and the pornographic. They imprison Billy Pilgrim and Montana Wildhack naked in a zoo on the planet Tralfamadore so Tralfamadorians may watch the humans mate.

“So far, Kurt, you have not fared well,” I’m thinking as I beg a cigarette from a teenager at a bus stop. I bow and she cups a lighter about my mouth. “It may as well be Bukowski or Palahniuk,” I mutter.

Under our cloud of smoke, the teenager nods in sympathy.

__________________________________

From the The Missouri Review Fall 2020 Issue by Mikka Jacobsen. Used with the permission of The Missouri Review.