Who other than Whitney Houston could stand in triumph on a winter night in Tampa and sing “The Star-Spangled Banner” better than it had ever been sung before? When Whitney stepped on that stage at Super Bowl XXV and brought the world to a hush with the all-time greatest rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” she was amid a hot streak most pop stars only dream of. She was the only artist to have seven consecutive number one Billboard Hot 100 hits, and she was the first woman to debut atop the Billboard 200 album chart. Whitney’s sensational rise was as much a part of her narrative as her miraculous voice and her famous kin. Clive Davis made sure of it, with his perfectly orchestrated rollout of her first two albums. Billboard called her “the pop equivalent of a De Mille extravaganza—epic and expensive.” She was Clive’s most perfect creation.

Of course, Whitney was made for this moment, she was the moment. Whitney had broken ground on MTV and in pop music, and her meteoric rise and streak of crossover singles made her the de facto voice of the post–civil rights era. Whitney was marketed as proudly All-American, Miss Beautiful with a voice that transcended all that divided us in this great country. So who else but Whitney could meet the moment? Who else had a voice that could touch everyone in that stadium and everyone watching from their living room?

It could have only been Whitney. She and all the other babies who straddled the Boomer and Gen X generations had seen society become more integrated. It was the era that cultural critic Touré pegged “cultural biraciality,” where a generation of kids were embracing cultures outside their own. Think about how many little Black boys who loved punk and rock and funk saw themselves in Prince’s chameleon-like approach to pop. Or how it wasn’t just young Black kids across the five boroughs or in Compton bumping LL Cool J and N.W.A. If the concerts didn’t tell you that, the war white women raged on rap most certainly did.

The “tough on crime” policies from the Reagan administration that inspired much of the “dangerous” hip-hop that sent white folks into hysterics were still ravaging Black American dreams in communities across the nation. Black men and women were either victims or villains, depending on who was asked. The tension of uncertainty already hanging thick in the Black neighborhoods was intensified by the Gulf War. Putting your body on the line for a nation that too often showed you how little it valued you and yours was heavy. For Black folks, the land of the free brimmed with oppression, even for our brave brothers and sisters who fought for the freedom of their country. Even if Whitney caught flack for her peppy pop tunes, she was still a Black girl from Newark with that voice, a voice that could inspire us all by singing the anthem like no one had sung it before—and like no one has sung it since.

No one but Whitney could have taken the anthem and breathed so much life and meaning into it.“If you were there, you could feel the intensity,” Whitney said in a 2000 interview. But even if you weren’t there, you could feel it. Millions watched the sound of her voice explode like bombs bursting in air—astonished that a voice that mighty came out of one person. Think about the moment. Madonna and Janet Jackson were volleying number one hits. Mariah Carey was the new pop queen then. Prince was taking us on orgasmic sonic adventures and reinventing himself time and time again. And Michael Jackson had entered his Dangerous era. We worshipped MJ, but he had all but evaporated into the image of whiteness. Michael had shed his Blackness in a physical sense the way we believed Whitney shed hers in her music and public personas.

The victorious feeling Whitney Houston baked into the anthem is why we thumb our nose at those who are unable to make us feel like we are basking in victory after they’ve sung “The Star-Spangled Banner.” When Fergie turned the anthem into a burlesque romp or Christina Aguilera forgot the words or some moderately famous singer in over their head hit a sharp note, we turn their failure into our entertainment—sending them into the ether of the Internet for our forever judgment and ridicule. Six months before Whitney sang the anthem, Roseanne Barr screeched her way through it before a San Diego Padres game. It was a trainwreck. And to make it worse, Roseanne spit and grabbed her crotch during the performance. Death threats and anti-Semitic rhetoric followed, because there’s nothing more American than destroying celebrities who do stupid shit. Her Saturday cartoon got nixed. The president called her a disgrace. Hell, Roseanne went viral before it was a thing—and got canceled before that was a thing too.

No one but Whitney could have met the moment. She had dropped “You Give Good Love” and “Saving All My Love for You” and “How Will I Know” and “Greatest Love of All” and—now, take a deep breath—“I Wanna Dance with Somebody (Who Loves Me)” and “So Emotional” and “Where Do Broken Hearts Go” and “I’m Your Baby Tonight.” Whitney was still a year away from ruling the world with “I Will Always Love You,” but she was already at the top when she stood on that winter night in Tampa with jets roaring in the air above her. No one but Whitney could have taken the anthem and breathed so much life and meaning into it.

In Tony Kushner’s landmark play Angels in America, there’s a snarky line about how the word “free” in the song’s lyric is set to a note so high, nobody can reach it. But there wasn’t a note too high for Whitney. Certainly not 1991 Whitney. Oh, the places her voice could go, and Whitney showed us just how far she could take her voice that night.

She was inspired by Marvin Gaye’s smooth rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” at the NBA All-Star Game in ’83. Marvin took the anthem and stretched it from its familiar 3/4 waltz into a smoldering soul record by grounding the hymn in a drum and keyboard track. But it was his swagger—effortlessly charismatic, yet sensuous—that sold it. The same way Whitney sold it when she stretched the anthem just as wide, filling the space with gospel flourishes and those money notes, those big runs that went sky-high, while dressed like an Olympic athlete.

The sheer magnitude of Whitney’s voice and her transcendent performance turned the anthem into a moment of pure elation and pride for country. But she was a Black artist singing an anthem that was built on the horrific oppressions of her people, and there’s a burden that comes with that—even if Whitney didn’t think about it when she stood on that stage and did what she did best.

See, we tend to forget—or ignore—the roots from which “The Star-Spangled Banner” sprouted. We don’t pass along the truths of which these lyrics were born—how white supremacy was at the foundation of these words we sing to pledge our undying patriotism. How could we? When we’re standing at ballgames dressed in jerseys to cheer on sports heroes, our hands on our hearts, these are the words we are asked to sing to evoke the pride of being in the land of the free and the home of the brave.

What are we to do with the ugliness that comes with loving a country with soil rich from the bloodshed of those who shoulder the trauma of its creation—from the pillaging of the land to the enslaved bodies that toiled atop it? The answer for Black people was to make their own anthem, and that’s why for the last century “Lift Every Voice and Sing” has been our rallying cry for liberation and a lasting symbol of Black pride.

In the battle over Colin Kaepernick’s right to peacefully protest the injustices of Black Americans by taking a knee during the national anthem, it was conveniently forgotten—or perhaps intentionally ignored—that the anthem is a product of Black injustice and continues to remain a symbol for it. This has always been a country that has benefited from the oppression and degradation of Black people—from the unconscionable terrors of chattel slavery to the hunting of our Black men and boys by white lynch mobs or the KKK or the police or whatever group of “very fine people” former president Trump told to stand back and stand by rather than explicitly condemn before some of those very people showed their allegiance to him by storming the Capitol in his name. The fact that there was still a contentious election after four years of Trump’s unrestrained racism and attempts at fascism forced those with the privilege to stop feigning ignorance over how deep-seated racism is in this country.

But even after the summer of unrest in 2020 pushed people into the streets during a global pandemic to march and put their bodies on the line to make the Black Lives Matter movement the most impactful racial movement in modern history, white conservatives were more up in arms about stores being looted and athletes continuing Kaepernick’s mission than they were about the loss of Black lives at the center of it all. But for Trump and his cult, or the conservatives who have bashed Kaepernick’s cause and trash BLM with their All Lives Matter rhetoric, it was never about defending patriotism. This was about upholding supremacy. A biracial man had dared to use the ugly history of the anthem and its complications for Black people in America to shine a light on the continued mistreatment of his people, and he was called unpatriotic. He was labeled anti-cop, anti-military, anti-American. A football quarterback was painted as a traitor for using his fame to force the white folks who loved to watch him throw that ball down the field to confront the oppressions of Black men and women in this country. Kaepernick got death threats and was essentially stripped of his football career. All for taking a knee during “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

I once had a white conservative friend tearfully explain to me why it was so awful that Kaepernick was distracting from games and why he needed to be more grateful about his wealth. Distracting. Grateful for his wealth. That’s what she fixed her white mouth to say to a Black man. I asked her about the anthem’s history. She couldn’t tell me a single detail. I asked her about the song’s third verse, which we don’t talk much about. She couldn’t recite a line. I mentioned doing away with the ritual altogether, or replacing it with “America the Beautiful” or “God Bless America.” She hated the idea but had no actual reasoning as to why. She was committed to her anger. A Black athlete didn’t just shut up and throw the ball for her entertainment and collect his millions. He was ungrateful. He was a distraction. Funny how that works.

It’s important we go back to 1814, when Francis Scott Key wrote those lyrics as the flag waved majestically after battle. Key was a lawyer and an amateur poet. Born into slaveholding wealth, he fought to uphold the practice. Key became an advisor to President Andrew Jackson (himself a wealthy slaveholder), who nominated him as the U.S. district attorney for the nation’s capital. During his time in office, Key worked to suppress the abolitionists who founded the anti-slavery movement, and he aggressively prosecuted slavery laws, even seeking the death penalty for an enslaved nineteen-year-old man accused of trying to murder his enslaver.

Because of Key’s influence, Jackson named Roger Taney (Key’s best friend and brother-in-law) to be chief justice of the United States, and he went on to author the Dred Scott decision in 1857, which upheld enslavers’ power, even in free states, and denied citizenship to free Black people. Key, like Jackson and like Taney, didn’t believe Black people were entitled to any rights. To Key, Black people were untrustworthy and lazy. A nuisance to white folks. As he put it, Blacks—free or not—were “a distinct and inferior race of people, which all experience proves to be the greatest evil that afflicts a community.”

That gets lost when we allow the history of the anthem to be divorced from the man who penned its lyrics while relishing in the victorious sight of the battle flag still standing after the British bombardment. The rush of victory and the pride of country, of the men who fought for it, is the crux of patriotism. Of Americanism. “The Star-Spangled Banner” promotes that to the point where not standing for it has riled up enough people that it’s unlikely Colin Kaepernick will ever play in the NFL again. But those people almost never mention the song’s origins, or can even tell you anything about the third verse, which has been lost to time and shame in the hundred years since it stopped being sung.

Before the refrain we know so well—“And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave / O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave”—Key derided the thousands of former slaves who joined the British in exchange for a passage to freedom in Canada: “No refuge could save the hireling and slave / From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave,” the lyrics go. Holding the contradictions of patriotism and oppression that sit at the core of these lyrics makes performing the anthem while Black so deeply complicated—and makes what Whitney accomplished on that night in the winter of 1991 all the more remarkable.

It’s one of those moments in time that is seared into our minds: Whitney standing in the fullness of her power, dressed down in that white tracksuit with red and blue accents and white Nike Cortezes—her arms stretched wide, head tilted back as she belted the high note like a gold medalist clutching victory. Picture it. Remember the beauty of her voice? That voice. The sweat dotting her face as she sang with all her might on top of the prerecorded track. That feeling. The emotion of it all. Whitney sang like she was at the pulpit giving glory to God. I can still see the flashes of faces caught by the camera, tears freely staining people’s cheeks as they waved tiny American flags. She made it look so easy, while making us feel so much. In that moment, Whitney offered the pride and joy of country while easing the fear over the Gulf War, which had started ten days prior and cast a shadow of anxiety—and extra security—over the Super Bowl.

The focus in her eyes, the warmth coming from her soul when she hits her peak, the cymbals punctuating the ferocity in her voice as she worked toward that extraordinary climax. It felt like she held those big notes for an eternity: “Ooooo’er the land of the freeeeeeeeeeeee and the hooooooome of theeeeeeeeeee braaaaaaaaaaave.” Think about her standing there, sweaty, arms stretched out in triumph, dressed like she’s running track for Team USA. Doesn’t it fill you with pride? The physicality of it all. Her voice, pouring into the microphone at full power despite the security of a prerecording blasting out the loudspeakers. This was a live sporting event, not a concert. Whitney was the sideshow, barely even the opening act when you think of all the pomp that comes with a Super Bowl.

But what she did on that dais? Nothing else about that night in Tampa even mattered. Most people can’t tell you who played in the big game, but they can tell you precisely where they were when they saw Whitney stand there and sing the anthem with all her might. The night she stole America’s heart and became a hero. There’s Whitney before the anthem and Whitney after—that’s just how big this thing got. An anthem born from the hands of a man who wanted to continue chattel slavery redefined by a Black woman whose majestic interpretation turned these lyrics into a Top 20 pop hit.

Try to remember the moment. For two minutes Whitney stood in the absolute peak of her brilliance. There was no chatter of her music not being “Black enough”; there was no sneering about who she was; there was no discussion about how she lacked the edge of Madonna and the moves of Janet or how she lacked enough singularity outside of her voice. In that moment all that mattered was that voice and its power. In those two minutes, Whitney became the embodiment of the ultimate American dream. She had reached the mountaintop, and the sheer magic of her voice moved the country to fall in love with itself a little deeper. And that is Blackness at its core. Whitney took the anthem, and all the darkness it casts down on Black folks, and transformed it into something that moved the world. In some ways, that night in Tampa was the Blackest thing Whitney has ever done—even if she, or any of us, didn’t realize it then.

__________________________________

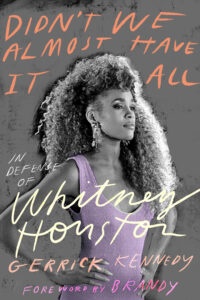

Excerpt from Didn’t We Almost Have It All: In Defense of Whitney Houston published by Abrams Press © 2022.