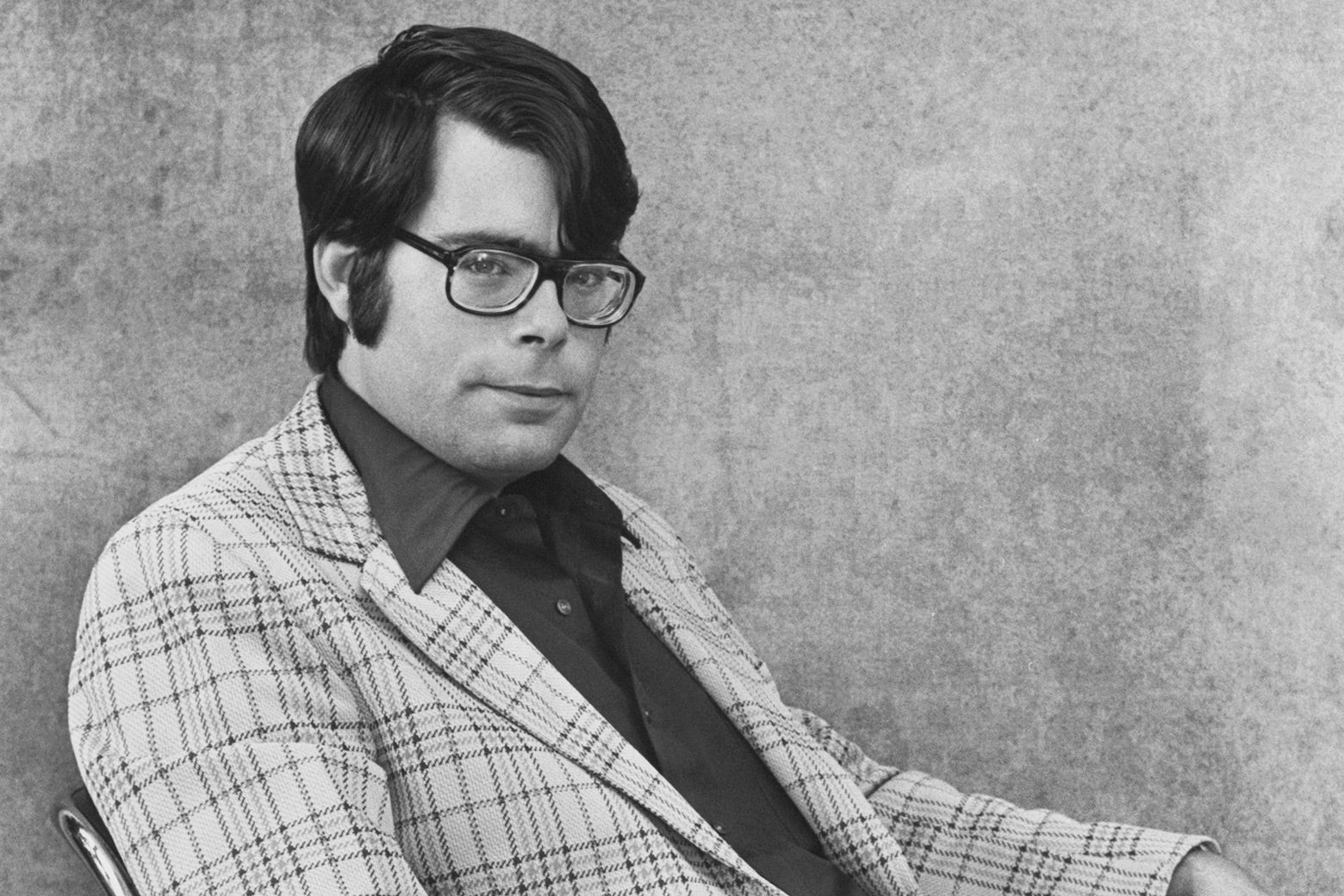

In 1978 Stephen King was finally riding high. After years of toiling in semi-obscurity, tirelessly peddling his short stories to regional literary journals and leering men’s mags, King saw his debut novel, 1974’s Carrie, become a surprise paperback bestseller, then the basis for Brian De Palma’s hit film. King followed Carrie’s success with ’Salem’s Lot in 1975, then The Shining in 1977, then The Stand in late 1978. Among the general public, King was building a reputation as a workmanlike factory of the sort of genre paperbacks that could be optioned by Hollywood before they even hit airport bookshelves—indeed, reviews of King’s early novels (to the extent that mainstream critics acknowledged them at all) often seemed to dismiss them as glorified movie treatments.

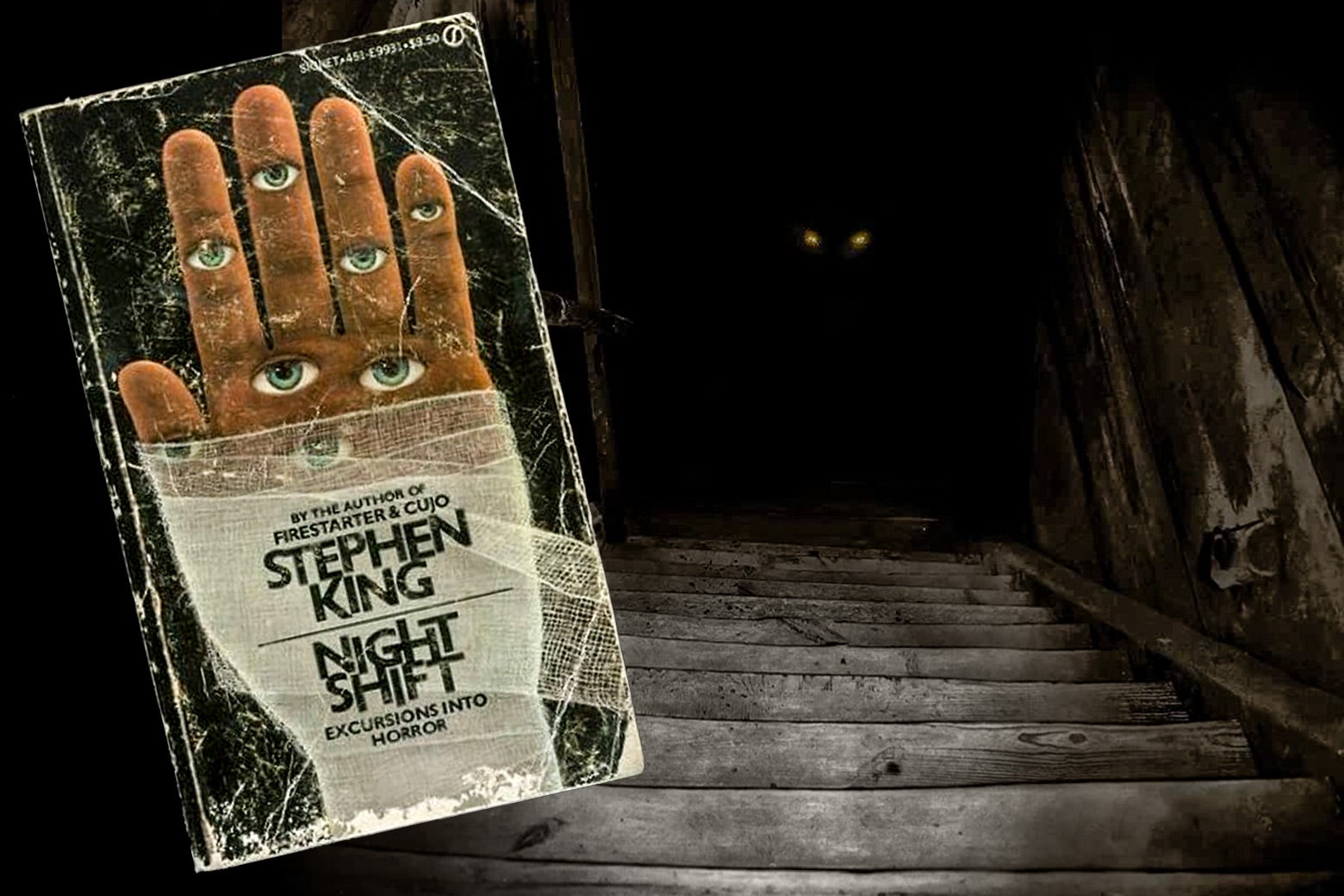

But in between The Shining and The Stand King published a book that complicated that image and, perhaps more than any of those others, foreshadowed the extraordinary career that was to come: Night Shift, a collection of those works from the pages of publications like Ubris and Cavalier, written back when he was a hungry comer. The tales in Night Shift are well-crafted and preternaturally fluid works of storytelling, with a master’s sense of structure and suspense. They also are the earliest evidence of King’s greatest gift: his twisted and seemingly inexhaustible imagination.

This Friday sees the release The Boogeyman, a feature-length adaptation of one of Night Shift’s stories—one that, according to IMDB, has already been adapted twice before, in 1982 and 2010, each time as a short film. (King has a longstanding policy known as the “Dollar Deal,” in which he allows aspiring directors to adapt his short stories into short films for a fee of $1; Frank Darabont, who’d go on to direct the Oscar-nominated King adaptations The Shawshank Redemption and The Green Mile, is one notable alum of the Dollar Deal initiative.) I haven’t seen the new film, and it remains to be seen if it will live up to its terrifying source material or fall short as so many King adaptations have—but if there’s any justice, it will at least occasion a renewed and overdue celebration of Night Shift and King’s short fiction more generally.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

For all of King’s well-deserved renown as a novelist, the stories in Night Shift represent some of the most purely terrifying work of his career. King was always a more graceful and inventive prose stylist than his detractors gave him credit for, but from the very beginning his true genius has been for ideas, horror hooks that can produce chills even from a one-sentence logline. A lonely girl with a fearsome gift takes revenge on the town and mother who tormented her; a father and failing writer slowly goes insane in an isolated, malevolent hotel; a cemetery brings beloved pets who are buried in it back to not-exactly-life. King’s novels that don’t work—and even a die-hard fan would admit that there are more than a few of those—tend to falter not so much because their core conceits are bad, per se, but rather that they are just neither sturdy nor dynamic enough to support hundreds (and hundreds) of pages of extraneous padding.

King’s short fiction doesn’t have this problem. The inherent economy of the form means that the idea itself is the star of the show. Each story is like a guy who shows up to the campfire, tells the scariest yarn you’ve ever heard in your life, then promptly leaves before anyone can fuck it all up by asking him to elaborate. The first time I read Night Shift as an already King-obsessed tween in the early 1990s, I remember the table of contents alone sending chills down my spine. What fresh hell lurked behind titles like “I Am the Doorway” or “Sometimes They Come Back” or “I Know What You Need”?

“The Boogeyman,” first published in Cavalier in 1973, exemplifies the best sort of work found in Night Shift. It’s a sleek, fiendish, and deceptively creative masterpiece, as well as a thrilling early flash of many of the hallmarks that would come to define King’s later horror fiction. In the story, a man named Lester Billings shows up in the office of Dr. Harper, a therapist, professing a desire to unburden himself about the deaths of his children. All three died suddenly in their cribs, deaths that the police and medical authorities are content to chalk up to grim coincidence: SIDS, then a seizure, then a freak accident. Lester knows better, though. Before dying, each child wailed “boogeyman!” while gesturing toward a closet door.

Nasty, brutish, and short (in my own well-worn, mass-market paperback copy of Night Shift it clocks in at 12 pages), King’s “The Boogeyman” is nothing but rising action. The story’s hands are dirty from its very beginning—King’s out here offing toddlers, for God’s sake—before it finally arrives at a twist ending that’s made all the more terrifying by the fact that you kind of see it coming, albeit through the cracks between your fingers.

A different (lesser) writer might have been inclined to make Lester Billings a sympathetic character—this poor guy has lost three kids to a monster who lives in his closet, after all. But King’s Billings is a complete piece of shit, a guy who casually drops racial epithets, brags about beating his wife and children, and doesn’t even really seem all that sad that his kids are dead. It’s clear that what’s brought him to this office is more cowardly, self-pitying guilt than anything like real grief.

This crucial choice—to make the story’s victim into a villain himself—is a stroke of genius on a few levels. For starters, it adds an unexpected humor to the story’s denouement: By the time you put it down you’re trembling, but part of you is also chuckling. (King has always been a funny writer, and quite a few of the stories in Night Shift—“The Mangler,” “Battleground,” “The Man Who Loved Flowers”—also work as particularly gruesome jokes.)

It also represents a devilish sleight of hand with regards to where the terror in this story actually lies. The boogeyman is a monster by definition, of course, but Lester Billings is a monster too, and King knows that we know that monsters of Billings’ variety are real. Readers were coming to understand that King’s horror fiction would often play with these distinctions-without-difference. The Shining’s Jack Torrance is a violent husband and father with alcohol and anger issues even before the Overlook gets hold of him—the hotel doesn’t so much corrupt him as it unlocks something that’s already there. Pennywise the Dancing Clown is one of King’s most celebrated creations, but I’m not sure he’s any scarier than It’s flesh-and-blood terrors, like Dorsey and Eddie Corcoran’s abusive stepfather.

Many of the stories in Night Shift feature nominal protagonists who are, at varying levels, distasteful human beings. “Children of the Corn”—probably the most famous story in Night Shift, if only due to how many times it’s been adapted and franchised for film and television—features an unhappy couple who are so consumed with bickering with each other that they’re slow to realize the horrifying situation they’ve stumbled upon. “Quitters, Inc.” introduces us to a self-involved businessman who just might love smoking more than he values the well-being of his wife and son. The protagonist of “The Lawnmower Man”—the strangest and funniest story in Night Shift—is a suburban cheapskate who hates his neighbors because they’re Democrats. The fact that we’re already hoping for these characters’ comeuppance makes the horrors to which King subjects them all the more thrillingly sadistic.

Night Shift’s publication, and success, was the first signal to King’s growing mass audience of what would become one of the quirkier and more paradoxical characteristics of his long career: Though he’s known for writing doorstops, his most frightening and often flat-out best work has come when he’s working short. His next collection, 1985’s Skeleton Crew, collected stories published in the early 1980s in between novels, and it’s similarly fantastic; the 1982 quartet of novellas Different Seasons contains some of the best and most affecting writing of his career, including Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption and The Body. Even in the 21st century, as he’s moved to publishing in such highbrow venues as the New Yorker, Esquire, and Granta, his short stories remain sharp, funny, surprising, terrifying. But it all started with Night Shift, one fresh hell of a beginning.