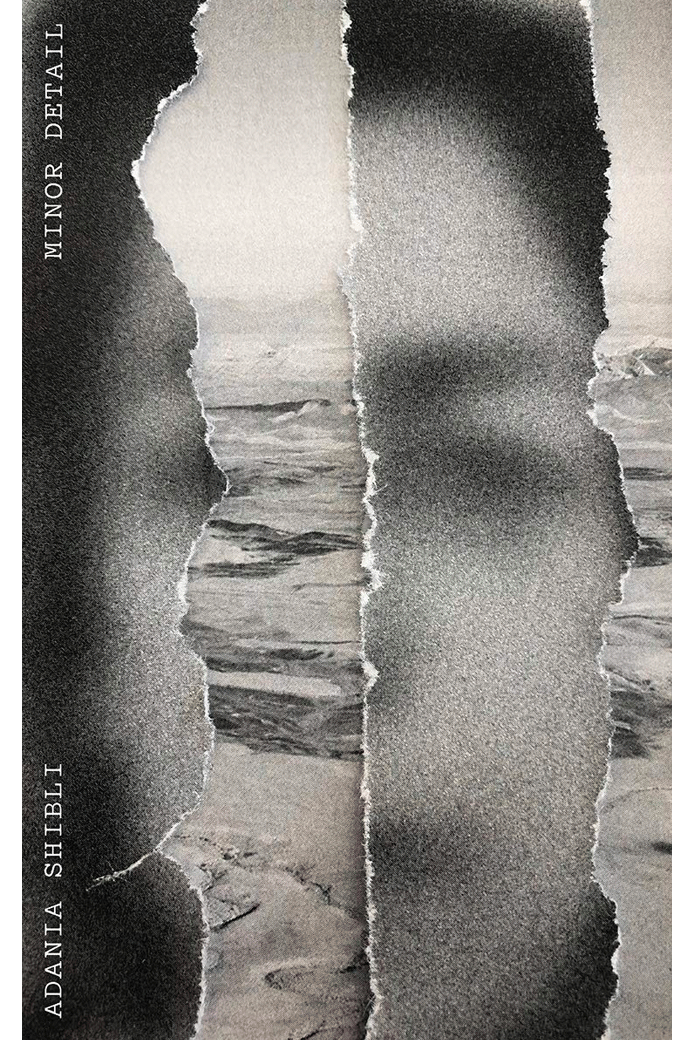

Back in August, I put the Palestinian novelist Adania Shibli’s Minor Detail on the syllabus for a novel-writing course I teach. I put it there because it is a complex, risky, beautifully crafted novel, containing so much more than its 105 pages has any right to contain. I’ve read it three or four times, and each time I’ve come away with a sense that it is one of the best novels I’ve read in the past decade. It’s not an easy book, but it’s an important one.

As the date approached for us to read and discuss the book, the world exploded. By the week after the Hamas attacks in southern Israel on Oct. 7, the book had become a kind of flashpoint. The Frankfurt Book Fair was to be held that week, and while there were plans to present Shibli with the prestigious LiBeraturpreis Award in person, the event was postponed in the wake of Hamas’ attack. An uproar ensued in the literary world; an open letter circulated by ArabLit (there were a lot of open letters circulating in those weeks) quickly accrued hundreds of signatures.

With more than a thousand Israelis murdered and taken hostage by Hamas and an unfolding war in Gaza, teaching this material would take more contextualization than I’d prepared for. People were losing jobs and job offers over their commentary on the conflict. I was not alone in feeling abandoned by an American left that seemed to turn away entirely from the horrors that had unfolded in southern Israel, and for the first time in almost two decades of teaching, I was actually a little afraid to hear what my students were saying—if only because I wanted to continue to love them as I’ve always loved them. On campus here at Bryn Mawr College, where in our Tri-College Consortium I teach students from Haverford and Swarthmore Colleges as well, there was no shortage of tension outside the classroom. Sit-ins, protests—posters with both impassioned and conflictual language were removed from dorm room hallways.

So. I won’t lie—I had my apprehensions about tackling it all in the classroom. The dominant media narratives about college campuses were and continue to be about hostilities and anger, and while I hadn’t felt any of it in the waters here, I hadn’t dipped in a toe. But it felt like the right challenge. While I’ve been steeped in reading about Israel/Palestine since before I had a choice—many Eastern European relatives of mine fled Nazi-occupied Europe for Tel Aviv in the ’40’s and ’50s; I have relatives across Israel, and friends across Israel, Palestine, and the region—I decided to read a pile of books in three weeks to responsibly prepare to teach this single short novel, in wartime. I view my classroom as a kind of collaboration, so I checked in with my students to see if they still felt prepared to read the book.

They did.

Minor Detail is a dark duet, told in two starkly contrasting voices. The book’s first half takes up the story of an Israeli general in the Negev desert in summer 1949, not a year since what Israelis call the founding of their state, and what Palestinians refer to as the Nakba, the “catastrophe.” In the novel, a group of soldiers led by an unnamed officer turned psychopath by a venomous spider bite murders a group of Bedouins, who leave behind a dog, and a girl, “curled up inside her black clothes like a beetle.” The officer sexually assaults and eventually murders the girl.

In the second half of the book, we’re introduced to a first-person narrative from a young Palestinian woman in the West Bank who reads a present-day newspaper article about this massacre. Hers is a uniquely searching and jumpy voice—in a blurb for the book, Nobel Prize–winning novelist J.M. Coetzee calls her an “amateur sleuth high on the autism scale,” though I’m not sure a close reading of the book reveals that exactly. She grows obsessed with the events after she discovers they transpired on her birthday. She travels through Israeli checkpoints in an attempt to find the location of the events in the Negev, only to meet a horrible fate of her own. “The borders imposed between things here are many,” she says early in her narrative. “[But] as soon as I see a border, I either race toward it and leap over or cross it stealthily, with a step.” Particularly with a hot war having broken out in Gaza, it seemed necessary we have at least some context for the book’s events.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

At the end of class, the week before our discussions, I gave a painfully brief lecture on the broad outlines of the conflict itself, from the 1880s to the present. I knew many of my students had been out protesting the killing of civilians in Gaza. I could tell they were, in some cases, feeling very heated over it. So I started by promising them two things: I would try as hard as I could to mention only facts, names, and dates which the average Israeli and Palestinian would agree upon, and I would correct any mistakes I made as soon as I discovered them. For close to an hour I said things like “1897,” and “Ottoman Empire”; “Balfour Declaration” and “Arafat” and “Dayan”; and and and. It took me about seven minutes to start saying “Camp David Accords” when what I meant was “Oslo Accords.” I muddled through. We learned things, together. As soon as we started talking about facts, asking questions, taking notes, the temperature in the room came down. It was no longer heated. It helps when we all admit that we don’t know what we don’t know, and that in this case in particular, there’s a lot we each don’t know.

At the end of that first day, we had a brief discussion about how they were feeling, and I made a distinction for our discussions going forward: It felt important to draw a line between those of us who were actively grieving the loss of people, or supporting grieving people who’d lost friends and family in the war, and those who were mainly tackling the material as a geopolitical idea. My own closest creative collaborator for the past four years, the director and co-writer of a feature film currently in development, is from Tel Aviv, and her aunt had been murdered by Hamas on Oct. 7. The director had been working on a peace project in Gaza for many years, and many of her close Palestinian friends in Gaza had stopped returning texts. She was scared and scarred, as I was for her.

At the time, I discovered, I was the only one in the room who was talking regularly to friends who were affected by harm to their own friends and family.

Then, the Saturday before we began discussing Minor Detail, the lines blurred for us again.

The stakes rose palpably.

News came that a Haverford junior, Kinnan Abdalhamid, a friend to a number of my students and a classmate to all of them, had been shot along with two of his Palestinian friends while on the Thanksgiving holiday in Burlington, Vermont. It was immediately apparent the attack was a hate crime, entirely unprovoked, horrifying. It was immediately apparent the lines between geopolitical concern and personal concern had been obliterated for us. I asked once more over email if we were still OK to tackle the book.

We were.

So that Wednesday we began class with a brief writing prompt: Take out a piece of paper. Write down one thing you’ve thought, or wanted to say, about the Israel/Palestine conflict since Oct. 7, but felt you couldn’t safely say aloud. I like to start class with five minutes of writing to collect our thoughts, and in this instance it felt particularly important. Social media has trained us away from privacy, from discretion, even. This felt like an especially good time to test out writing a thing before potentially saying it.

When we finished writing, we all folded up that paper and put it away. We could articulate it or keep it to ourselves going forward.

What ensued over the next couple of hours was the opposite of the stories we’ve been hearing about what has been happening on college campuses over the past months. In our first hour, we tackled only the first half of the book, in which Shibli enters the head of this murderous officer. Why has she chosen to enter this mind, to attempt this almost audacious act of empathy, rather than, say, telling the story from the Bedouin girl’s point of view? While we don’t get any of the officer’s emotions in Minor Detail, only what one student called “procedural” descriptions of his days, we do see much lyrical physical description of the desert, which seems to come from within his mind; “nothing moved except the mirage,” the book opens: “Vast stretches of barren hills rose in layers up to the sky.”

Before we knew it, we were finished for the day. A student came up to me on their way out the door and it was as if we were both suspended over the edge of a cliff, not yet certain if we were about to fall together. “Thanks for this,” they said. “This is the only class I’ve taken where we’re actually talking about this stuff.”

Here’s where I’ll confess to you what I didn’t say in the classroom: I don’t really know what to think about the current conflict. Thinking about the conflict is and has been a game of emotional and intellectual pingpong. I mean, I know I’m horrified by the murder of civilians and am desperate to see it end. But beyond that. After. As a Jew in America, I know the word “Zionism” has devolved into a kind of Wittgensteinian private language, a term with meanings so varied from person to person in their usage that it has come to essentially lack any real significance at all. I do not think the current, catastrophically corrupt Israeli government has any plan for the day after. But I’m also quite certain the phrase “from the river to the sea” is genocidal language, no matter how we quibble over it.

But here’s the thing: I didn’t say any of this in the classroom because that’s my job. It is not our job as professors to utter every opinion that comes into our heads. Our job is not to teach our students what to think. Our job is to teach our students how to think. Which is exactly why I take it as my charge to teach Minor Detail. Do I love spending 50 pages in the head of a psychopathic Israeli general for the same reasons, say, Adania Shibli might have put me there? Of course not. But that’s the whole point of reading novels, and the reason the book is so beautiful. It resists easy answers. It is not a polemic. It is a work of literature that signifies multiply and challenges our assumptions. I’ve been thinking a lot about the work of W.G. Sebald since teaching it—when he first began giving On the Natural History of Destruction as a lecture in the late 1990s, he was essentially the first public intellectual to lay out the horrific bombing of German cities at the end of World War II. It should not have taken 50 years for us to be able to think about it. It did not absolve Nazi Germany one whit. But it was necessary.

This might also be an ideal moment to mention that I wasn’t presented with really any Palestinian novelists at any point in my own education. In high school we got our steady diet of Hemingway and Fitzgerald, a little Chinua Achebe. Though I went to one of the most storied English departments in the country as an undergrad, the closest we came was reading Edward Said in postcolonial theory courses. That said: I wasn’t presented with a single Jewish or Israeli novelist in that period, either. I found Philip Roth’s Goodbye, Columbus on my own, and couldn’t believe how closely it hewed to my own experiences 30 years later. There were stories that so closely mirrored my own I could hardly believe it. By the time I was in my late 20s and early 30s I was deep into Saul Bellow and David Grossman, Etgar Keret and Amos Oz. It probably wasn’t until I was in my late 30s that I read the Quran, dug into Fady Joudah and Mahmoud Darwish, and began to find writers like Adania Shibli. And I’m a person who has given my life over to reading.

Which is all to say two things: First, that if we’re quick to criticize the average 20-year-old for not having a sophisticated historical and literary historical background while they’re out protesting horrific images of civilian death … maybe it’s us who could stand to have some context about what we’re criticizing. It’s surely not lost on any close reader of Orientalism that Said’s central point is not just that the conflict between Orientalism and the West is bad—but that the binary itself is the problem. No binaries. And the second point: It’s on us to present those same kids with books like Minor Detail in the classroom. I just couldn’t have put such a fine point on it until being forced to think about it more deeply for the past two months.

A lot happens every week now, in Gaza, and here in the States too. A student was arrested by the FBI for making death threats on Cornell’s campus. Protests, and counterprotests, and counter-counterprotests on Columbia University’s main campus. Campus campus campus. Anger anger anger. It all felt like a lot, too much to parse. More than anything it felt like there was a related, but separate, conflict playing out here in the U.S., a battle over bombs falling so far from us, images coming back so close, so disturbing.

All the while, learning continues apace in college classrooms. In mine, we came into our third and final class about Minor Detail more confident. I asked what the main thing was we’d taken home from the last class, and as a group we all agreed: While of course the material is political, with a point of view, it’s very much not a polemic. Narrating the first half of the book from the officer’s point of view was bold and full of risk, but it was the only way to tell it.

The second half of the book is in its own way more harrowing. It ends with the narrator being shot by a group of Israel Defense Forces soldiers who see her outside her borders. The final paragraph is as painful as any in literature: “And suddenly,” Shibli writes, “something like a sharp flame pierces my hand, then my chest, followed by the distant sound of gunshots.” What precedes this is so much of what we all had been thinking about: what it feels like to move through IDF checkpoints. A list of the names of Palestinian villages in their Arabic names. We get a lot more of this unnamed narrator’s emotions, but we’re still at arm’s length from the world she tours us through. We get the minute description of her trip, her detective work to discover the location of the massacre imagined so minutely in the first 50 pages of the book.

Amid those descriptions, Shibli’s narrator tells us: “There are some who consider [my] way of seeing, which is to say, focusing intently on the most minor details, like dust on the desk or fly shit on a painting, as the only way to arrive at the truth and definitive proof of its existence.” I’m honestly not sure which of us was the first to say that that’s just what’s been making it so impossible for us to talk about these things since Oct. 7. That it has all been far too big to take in, to comprehend, to process. “Maybe that’s why there are novels,” one of us said.

And at that point, our time was up. Three days of talking about 105 pages of a short novel about an impossibly big subject. It was hard to know just what to say: I for one was feeling grateful, a proud papa. We’d made the hard choice to persist with a hard book in a hard time. I was speechless. Just as I was about to make some lame final comment, a student said there was one passage she was disappointed we hadn’t discussed. She asked if she could read it. Almost at the end of the novel, Minor Detail’s narrator hears something: “I listen intently to the sounds of the shelling,” she says, “and the heaviness of the sound translates my distance from the place being bombed. It’s far, past the Wall. In Gaza, or maybe Rafah. Bombing sounds very different depending on how close one is to the place being bombed, or how far.”