“Poor Spidey. He was almost never born!”

Those were the words of Spider-Man’s cocreator Stan Lee, remembering all the arguments that were used in 1962 to convince Stan not to bring Spider-Man into the world. Stan’s then-boss Martin Goodman, voicing the common wisdom of the day, had a highly negative reaction to Stan’s idea for a new character to be called Spider-Man. Goodman’s objections were many. Allow me to cite a few: People hate spiders. Teenagers can only be sidekicks. A super hero shouldn’t have so many problems. He should be handsome and glamorous and popular. Well, you folks get the picture.

The estimable Mr. Goodman, whose criticisms were not to be taken lightly, was not pleased. Stan was allowed to go ahead and use the sure-to-be unpopular new character in the final issue of a comic book called Amazing Fantasy, cover-dated August 1962. And then the book was canceled. Stan and his artist Steve Ditko had been creating stories for that title since its inception, when it was called Amazing Adult Fantasy, presenting a fine variety of fantastic, short illustrated stories with a bit of a science fiction bent to them. It was somewhat different from the other titles the company was publishing at the time, such as Strange Tales, Tales to Astonish, and Journey into Mystery.

Those comics featured monsters and alien entities arriving on our poor planet to conquer it, and they boasted outrageous monikers such as Monsteroso, Fin Fang Foom, Zzutak, and my all-time favorite, Googam, Son of Goom. Now that’s a name to conjure with.

At this point, a bit of historical perspective is needed. The legend goes that in 1962 Martin Goodman, the owner and publisher of Atlas Comics, went golfing with an executive from the rival comic book company National Periodical Publications. During that golf game, Goodman learned that National was finding success with a title featuring a super hero team called the Justice League of America. Goodman immediately asked his chief editor/writer, Stan Lee, to come up with a super team that Goodman could publish. The title that Stan dreamed up with artist Jack Kirby was The Fantastic Four. Stan and Jack quickly followed it up with The Incredible Hulk, which Stan described as a combination of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and Frankenstein. Spider-Man was Stan’s third entry and the one that met the most resistance.

It’s been fairly well established that Stan again chose Kirby as the penciler on the first Spider-Man story with Steve Ditko on board as inker. Details on what happened next are a bit hazy, but apparently this first version of the character bore little resemblance to the one that readers around the world became familiar with. It’s said that Kirby created five pages that had some teenager possessing a magic ring that somehow changed him into an adult hero named Spider-Man. Stan decided to go in a different direction, hiring Ditko to take over as penciler.

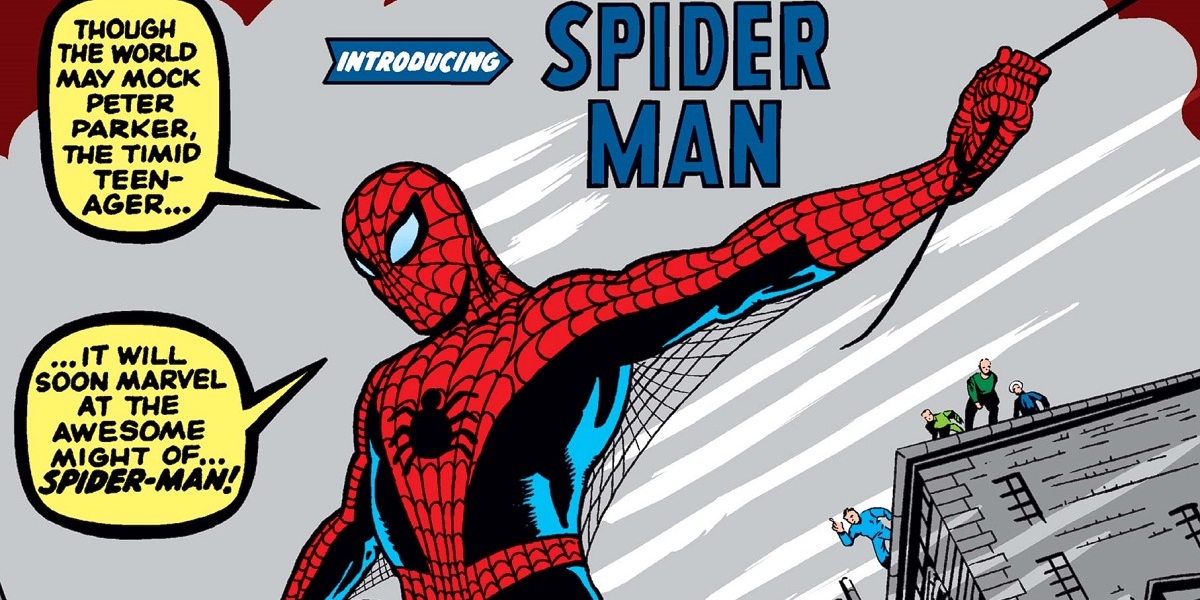

The subversive nature of Spider-Man took hold as I was enthralled by the exploits of a hero (or antihero) whose very existence seemed to undermine the role of a traditional super hero.Stan altered his story synopsis, and what Steve then penciled for Amazing Fantasy No. 15 was an 11-page tale that would forever change the super hero genre. That story contained all of the elements that Publisher Goodman objected to on the basis of it being wholly uncommercial. The hero of the story, Peter Parker, was a bookish, unpopular teen. He wasn’t handsome and glamorous. And, most egregious, he took on the characteristics of a spider. Ugh. Everyone, argued Goodman, hates spiders.

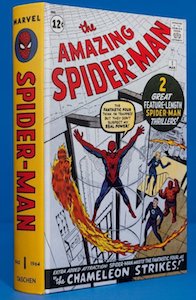

The kicker is that when the sales came in on that final, fateful issue of Amazing Fantasy, it was an unqualified hit, surpassing anything else the company published that year! No fool he, Martin Goodman swallowed his pride and then authorized the publication of a bimonthly (soon to be monthly) title called The Amazing Spider-Man, with the first issue cover-dated March 1963. The rest, as the cliché goes, is history.

Stan Lee had often said that his favorite artistic collaborator was Steve Ditko. It’s truly fortunate that Ditko replaced Kirby on Spidey due to the nature of this utterly unique character. When it comes to bombastic action scenes and mightily muscled costumed heroes in cataclysmic combat, Kirby simply had no peer. Thus, for almost any other series in the then-young Marvel Comics lineup, Kirby was the perfect penciler. But Stan had something very different in mind when he conceived of the web-spinner. There is so much that separates Spider-Man from the traditional super hero. Stan and Steve turned many of the elements from the Superman mythos on its head, creating something truly revolutionary. They broke the mold that had defined costumed heroes since their inception.

Instead of being loved by the public, Spider-Man, despite his heroic deeds, was viewed with suspicion and outright fear. J. Jonah Jameson and the Daily Bugle newspaper were counterparts to Perry White and the Daily Planet in the Superman comics. But where White and the Planet lauded the exploits of the Man of Steel, Jameson despised Spider-Man and used the Bugle as a platform from which he launched scathing editorials and articles about our hero.

Ironically, Peter Parker worked as a photographer for the newspaper, selling Jameson photos of the web-slinger in action because he needed the money. Stan and Steve actually turned the Superman status quo on its head and did it brilliantly. Whether this was intentional, I don’t know. And as a young reader of the comic at the time, it never was a connection I made consciously. However, subliminally, the subversive nature of Spider-Man did take hold as I was enthralled by the exploits of a hero (or antihero) whose very existence seemed to undermine the role of a traditional super hero.

Spider-Man became Marvel’s biggest success, right from his first appearance. Stan gave Peter Parker all the failings of a teenager. Once Peter received his miraculous spider powers, the last thing he wanted to do was go out and get a colorful costume and fight crime. Instead, he became a masked wrestler so that he could make some much-needed money. He intended only the best for his beloved, elderly family members Uncle Ben and Aunt May, but, in his words, “The rest of the world can go hang for all I care.” In your wildest dreams could you ever imagine Superman saying such a thing? It took the tragedy of Uncle Ben’s very preventable death to awaken Peter to use his strange powers for the good of society. No matter how much good he strived to do, however, Peter could never escape the guilt of knowing that if only he’d stopped one burglar when he had the chance, Uncle Ben would still be alive.

Instead of being loved by the public, Spider-Man, despite his heroic deeds, was viewed with suspicion and outright fear.Jump forward 30 years. When I edited the Spider-Man franchise back in the 1990s, Aunt May had already died in a truly touching tale in Amazing Spider-Man No. 400. I was determined to bring her back. Writer J. M. DeMatteis had crafted an emotionally resonant story about Aunt May’s death, but I still felt it was a mistake to remove her from the board. She is the physical embodiment of the guilt that Peter feels over his uncle’s death. Every time he sees Aunt May he recalls that it is because of his inaction that she became a widow. No other member of the cast can perform that function. So, it’s my view that frail, old Aunt May has to remain a part of Peter Parker’s life. Period.

So much of the humanity of Peter is shown through his interaction with his aunt, especially in the issues reprinted herein. His interactions with all the members of this marvelous cast, perhaps the best ever in comics, allows us to see the different facets of his character that each one brought out. Stan proves to be a master in this regard. Peter’s concern for Aunt May only grows along with his feelings of guilt. She almost succumbs to several illnesses, and the depth of Peter’s concern for her health supersedes anything else in his checkered life. The many scenes he has with her truly tug at your heartstrings.

On the opposite end, Parker’s interactions with his fellow teen and full-time tormentor Flash Thompson reveal other aspects of Peter’s personality. There’re only so many of Flash’s insults that Peter will endure before he shouts back at Flash, almost coming to blows with the bully on several occasions until Peter realizes that he could easily kill Thompson with his spider strength. Their battles come to a head in No. 8, the “Tribute to Teenagers” issue, when Peter and Flash finally attempt to settle their differences inside a boxing ring in the high school gym. The student body, largely composed of Flash Thompson fans, refuses to believe that Flash was actually beaten fairly because his head was turned when Peter delivered the knockout blow.

And in a very clever twist by Stan, Peter is able to use the boxing match to cast suspicion on Flash as possibly being Spider-Man, throwing Flash completely off-balance as he tries to defuse that accusation on the final page of the story. And that last panel should be savored because it’s a rare instance of Parker managing to come out on top of events for a change.

Bugle publisher J. Jonah Jameson usually treats freelance photographer Peter Parker as a necessary nuisance, as he does the rest of his employees. No one else can ever get the photos of Spider-Man in action that Peter does, so Jameson continues to use him. Even though he’s a notorious skinflint and a miserable man to work for, Jameson is imbued with a depth of characterization that prevents him from ever lapsing into parody. Jonah’s schemes to find some other super-powered stooge to convincingly defeat the web-spinner go awry so often that it’s hilarious. One such laugh-out-loud moment occurs in issue No. 18 when Jameson believes he has finally struck gold as the Green Goblin seemingly makes Spider-Man flee their battle in fear. The sickening grin on Jameson’s face, which seems frozen there throughout the story until early in issue No. 19, gradually fades as Jameson is informed that some of the facts don’t support his view of reality. That’s priceless.

Another pivotal scene with Jameson occurs on the final page of issue No. 10. Alone in his office, he reveals why he hates the web-spinner so much and must do all that he can to tear him down. In Jonah’s sad view, Spider-Man is everything he is not: selfless and courageous. Thus, all that’s left for this very successful newspaperman is to tear down the one man who makes him hold up a mirror to himself and expose the ugly truth. Within just three small panels, Stan Lee’s incredibly artful scripting gives the reader full insight into what makes one of the major players in the Spider-Man universe tick. Of course, Jonah’s understanding of himself hardly stops him from continuing his quest to destroy the web-slinger, with many more ambitious schemes yet to come.

Also, it must be added that this brief sequence in issue No. 10 has borne its share of controversy over the years. There’s a segment of rabid Spiderophiles who feel that this revelation came way too early in the series. They also believe that it was too blatant an exposé for a man such as J. Jonah Jameson to voice, betraying a sudden self-knowledge not evident elsewhere. I come down right smack in the middle of the controversy. While I agree there was no compelling story reason for Jonah to reveal his inner feelings about his spidery nemesis at that moment, it was a superb character reveal, emblematic of the entire Lee/Ditko run.

On the previous page of that story where Jonah soliloquizes, Spider-Man reveals in a thought balloon that he never thought Jameson was really that bad. It’s fascinating that after all the grief that Jameson has caused him, Spidey still is not able to think that poorly of him. And, in fact, in the years to come there are instances when Jonah shows some backbone in defending the integrity of print journalism against outside interference. He’s fiercely protective of the Daily Bugle; it’s his turf. Perhaps it’s a later addition to the staff, Editor-in-Chief Robbie Robertson, who brings out the better angels in Jonah’s nature.

However, in the issues printed in this volume, Jonah is a mogul on a mission, and the complex machinations he goes through to achieve his elusive goal have definitely provided some of the better story fodder in Amazing Spider-Man. Some of the series’ biggest laughs have come from those scenes where Spidey has gotten a little revenge on Jameson by webbing his mouth shut or webbing him to his chair or the ceiling. It’s nice to see the old skinflint get his comeuppance every now and again. That’s everybody’s secret wish: to be able to strike a blow against those who torment you.

______________________________________________________

Excerpted from The Marvel Comics Library. Spider-Man. Vol. 1. 1962–1964. Published by Taschen. Introduction copyright © 2021 by Ralph Macchio. All rights reserved.